The Logos, Resonant Utterance or Word

McLuhan's strategy can be seen within the context of ancient oratory, in the contributions of the presocratic philosophers who spoke the language of Logos. The Logos tradition is one of word compaction, word as irony, word as metaphor, and as resonance. McLuhan was a modern master of this form, using words as active principles of discovery. It was believed to be the truest form of communication. Practitioners of Logos were grammarians, speakers and writers who employed analogy and symbolism for the sake of perception. Grammatica is the first branch of the trivium, and is related to poetry. Grammatica in the trivium is the power of speech to leverage meaning. Grammatica is the language of perception, dialectic in contrast is the languages of concept. McLuhan's investigation of the trivium, tracing the rise and fall of grammatica, dialectic, and rhetoric in western culture, century-for-century, is the basis for his later writing on communication and language. McLuhan the poet was naturally a partisan of grammatica, and sought fellow poets of the modern period (Joyce, Eliot, Poe, Mallarmé, Pound) as objects of study. It was their effective use of words that might revive a primacy for perception. The dialecticians were by contrast willing masters/slaves of conceptual thinking, predestined to end up exactly where they began, that is, on familiar ground.

Arithmetica |  Astronomia |  Dialectica |

| |  Rhetorica | |

Geometria |  Grammatica |  Musica |

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

1 comment:

I've never read McLuhan, but ...

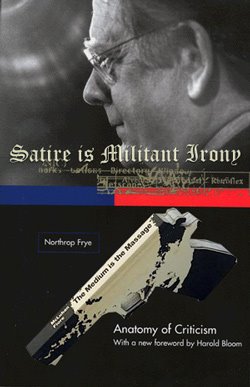

Why don't we read Marshall McLuhan today? Although trained as a highly specialized bookman and supported by an academic sinecure, McLuhan did little to guarantee his influence as a writer and scholar. From his earliest career, he ignored his peers. He wrote few books, and the ones he did write grew progressively more difficult. He did not train many graduate students who might have sustained his legacy. McLuhan treated his teaching responsibilities casually, his publishing commitments with utter disregard.

In a fascinatingly self-destructive manner, McLuhan signed his name to material he never wrote. Even after death, this practice continues. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century, "co-written" with Bruce Powers, was published in 1989 by the Oxford University Press, nine years after McLuhan's death. There are few clues in the introduction as to how this feat of post-mortem authorship was accomplished, but it appears that it was inspired by tapes of the authors talking with each other and sharing incomplete attempts at creating a manuscript. During his life, McLuhan published an unsuccessful newsletter, wrote confusing letters to business executives, made absurd pronouncements on television, and took little care to protect his dignity or enhance his reputation.

And yet we all know his name and his slogans. McLuhan's message has insinuated itself into the oral culture of the electronic age, and no amount of academic criticism or easy ridicule can remove it from circulation. McLuhan's slogans circulate because they are snappy but also because they have never been understood. Were they neatly wrapped up in a systematic sociology of media, they would be absorbed, superseded, and forgotten. His slogans are like lines of poems, or phrases from songs - capable of carrying powerful and ambiguous messages into new environments.

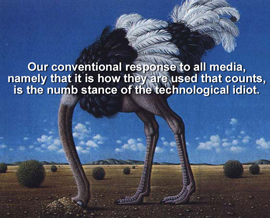

To some who venture from the slogans to the books, McLuhan will seem outdated, especially in his hope for a human engagement with media that goes beyond technological idiocy and numb submission. McLuhan's jokes and satirical put-ons were challenges to understand where our media were leading us, and there is no clear evidence that we have been able to respond to his challenge. It is comforting to think McLuhan is outdated, because it alleviates our shame at not living up to his demands. His pleas for understanding and his warnings of doom are like the quaint aphoristical exhortations and eschatological prophecies of the early church.

In the end, McLuhan's success stems from this failure, which was a form of martyrdom. He spread himself across too many media, he scattered his pearls before swine ("perils before our swains," as it says in Finnegans Wake), and he chopped up his promising scholarly career into hundreds of thousands of jokes, quips, bad puns, inane television commentaries, and letters to the editor. Respectable folk turned up their noses at his odor of sanctity, and the sage's reputation slowly died. But today McLuhan lives on, even composing books after his death, as electronic culture's immortal saint.

Post a Comment