The DEW Line was of course an integrated chain of some 63 radar and communication stations, stretching 3,000 miles across Arctic Canada at approximately the 69th parallel, from Alaska to the eastern shore of Baffin Island. Completed in 1957, a later extension connected eastern Canada to Greenland. Built at the height of the Cold War, with its threat of nuclear annihilation, the system was designed to provide advance warning of imminent air attack to Canada and the United States. The DEW Line became a perfect metaphor for McLuhan on the role of art and the artist at a time of rapid social and technological change and he repeated the idea frequently.

McLuhan would later memorialize this by speaking of Canada as a Dew Line with respect to media effects and their global impact (punning on the acronym, D.E.W., of the 1954 military Distant Early Warning System of radar built across the North of the Continent of North America by the U.S., as an early warning system against nuclear attack).

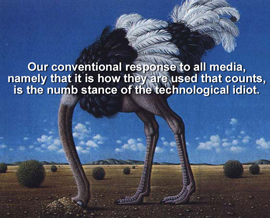

"I think of art, at its most significant, as a DEW line, a Distant Early Warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it."

Gary Genesko : The Dewline Newsletter and Explorations:Concerning McLuhan's journals, almost no critical attention has been given to them. I provide the following information as a guideline for researchers. Twenty McLuhan Dew-Line Newsletters were published by the Human Development Corporation in New York between 1968 and 1970. The format changed from issue to issue. The designs were adventurous, and several included supplementary materials such as slides and playing cards. It is difficult to find a complete set. Not even the University of Toronto Archives holds the complete run. For a brief description of McLuhan's commercialization at the hands of Human Development Corp. President Eugene Schwartz, see P. Marchand, Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and the Messenger (Toronto: Random House, 1989), pp. 199-200. Of course, McLuhan was no stranger to promotional activities, a good example of which appeared in a letter he wrote to advice columnist Ann Landers (December 17, 1969) concerning the virtues of the 'Dew-Line Deck' (the supplemental playing cards issued with II/3 Nov.-Dec. 1969) as a brain-storming device. Each card contained an aphorism in relation to which problems could be discussed, stormed, bounced off, etc. (See L etters of Marshall McLuhan, Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 393-4). The complete run included: I/1 Black Is Not A Color (July 1968); I/2 When You Call Me That, Smile (August 1968); I/3 A Second Way To Read War And Peace In The Global Village [included a Sensory Training Kit consisting of the book mentioned and an exploratory essay] (Sept. 1968); I/4 McLuhan Futuregram, No. 1 (October 1968); I/5 Through The Vanishing Point (November 1968); I/6 Communism: Hard and Soft (December 1968); I/7 Vertical Suburbs And High-Rise Slums (January 1969); I/8 The Mini-State And The Future of Organization (Feb. 1969); I/9 Problems Of Communicating With People Through Media (March 1969); I/10 Breakdown As Breakthrough (April 1969) I/11 Strike The Set (May 1969); I/12 Ad Verse: Ad Junkt [included slides] (June 1969); II/1 Media And The Structured Society (July-August 1969); II/2 Inflation As Rim-Spin (Sept.-Oct 1969); II/3 The End of Steel and/or Steal: Corporate Criminality Vs. Collective Responsibility [included playing cards] (Nov.-Dec 1969); II/4 Agnew Agonistes (Jan.-Feb. 1970); II/5 Bridges (Mar.-April 1970): II/6 McLuhan On Russia: An Interview (May-June 1970); III/1 The Genuine Original Imitation Fake (July-Aug. 1970); III/2 The University And The City (Sept.-Oct. 1970).

The other major journal was Explorations. The first nine issues are perhaps most well known since selections from them were published in book form as Explorations in Commmunication, edited by Edmund Carpenter and McLuhan (Boston: Beacon, 1960). The first issue of the journal appeared in December 1953, and number nine in 1959. But that was not the end of it. Explorations became "a magazine within a magazine" in the University of Toronto alumni association publication, the Varsity Graduate. Beginning in the summer of 1964, the VG (later U of T Graduate)contained an insert of selected articles, edited by McLuhan alone. These unnumbered issues ended with the Christmas issue, 1967. Explorations picked up again with issue 21 in March 1968, and this numbered series ended with number 30 in June 1971. The final two issues appeared in 1972. Explorations ceased publication in May, 1972. The length of the journal's run (1953-1959; 1964-1972), in one form or another, is not well known.

----------------------------------------------------

Television in a New Light

Canada is the land of the dew line (distant early warning)

system. As the United States becomes a world environment, it has grave

need of distant early warning systems as a way of discovering what's

happened. Culturally, dew lines are a very valuable device. Two aspects

of my operation at our Center for Technology and Culture in Toronto seem

to me of special significance to the future of television. One of the

things which we discovered in recent months is that in every society,

every new environment creates an intense image of the old one; the new

one is invisible. Bonanza is not our present environment, but the old

one; and in darkest suburbia we latch onto this image of the old

environment. This is normal. While we live in the television environment,

we cannot see it.

I am also mainly concerned with perception - how to see things.

Apropos of this, someone said the other day that Canada has no classes,

only the Mass and the masses. Canada was created by rail only a hundred

years ago, and owes everything to the railway - the joining of French and

English Canada together was a railway action. Rail is a profoundly

centralizing power. Now with the airplane and television and radio,

Canada is coming to an end. A country three thousand miles long cannot be

held together by rail while putting up with airplanes, radio, and

television, which are decentralizing forces. Separatism is a simple fact

of radio and television.

Radio and television, like electric lights, are profoundly

decentralizing separatist forces. They give everyone anywhere, whether

under the ice of the arctic or here, the same information, the same

space, the same facilities. Anyone who talks about centralism in the

twentieth century is looking at the old technology - Bonanza - not the

new technology - electric technology. Our children grow up in a world

that is integrated electrically, that is, a world in which everything

happens at the same moment. It's an "all-at-once world" of happenings.

Then they are put into school rooms and colleges where everything is

classified and fragmented - where subjects are not interrelated. And they

really are baffled. This is what Paul Goodman calls "growing up absurd."

What could be more absurd than to go from an electric, integral world

into a disintegrated, fragmented, mechanical world of the old

nineteenth-century technology which we call our school system?

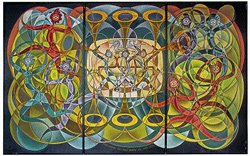

In the sixteenth century there was a painter known to us all by

the name of Hieronymus Bosch who painted this same dilemma in his

"Temptation of Saint Anthony" and other nightmares. The Sixteenth-century

experience was not unlike ours except that it was the reverse, sort of

negative to our positive. The old Medieval world of iconographic

sculptural space was confronted by a world suddenly integrated by visual

perspective space. So, in the "Temptation of Saint Anthony" you have the

old Medieval world of strange icons overlaid by the new perspective

Renaissance world of uniform, continuous, and connected space. To the

sixteenth-century person, this new world was an outrage because it

destroyed every known human value. What we now think of as the basis of

our whole civilization - namely uniform, connected, and continuous space,

rational space, rational order - was, in the sixteenth century, a

barbaric intruder into their order. Visual space was considered the

destroyer of all human order. Now we think of it as the basis of all

human order.

When electric circuitry comes into play, it creates not a visual

space at all, but an all- at-once simultaneous space. Consider the new jokes.

"Alexander Graham Koloski, the first telephone pole."

There is no concept of space, the joke has no starting line, no

connection: everything happens at once.

"What's purple and hums?"

"Well, naturally, an electric grape."

"Why does it hum?"

"It doesn't know the words."

These are totally irrational, not connected stories which our kids love.

This is the electric world, where everything happening at once is normal.

It is the world we live in and operate in, but not necessarily the world

we think in. Our thinking is all done still in the old nineteenth-

century world because everyone always lives in the world just behind -

the one they can see, like Bonanza. Bonanza is the world just behind,

where people feel safe. Each week 350 million people see Bonanza in

sixty-two different countries. They don't all see the same show,

obviously. In America Bonanza means "way-back-when." And to many of the

other sixty-two countries it means a-way-forward when we get there.

The electric world of separatism produces a world of disease and

discomfort and distress, which has in turn produced a whole batch of

jokes. In a wonderful little book, The Funny Man, Steve Allen says, "The

funny man is a man with a grievance." So, we have the grievance joke -

The cat is chasing the little mouse and the mouse finally eludes the cat,

dives under the floor and lies there panting while the cat prowls around.

After a while everything is quiet. The mouse begins to feel a little more

comfy and suddenly it hears a sort of "arf, arf, bow wow" sound and

decides the house dog must have arrived and chased the cat away. So up

pops the mouse. The cat grabs it, and as she chews it down the cat says,

"You know, it pays to be bi-lingual." Another example - The president of

Canadian Shell is talking to the president of American Shell a couple of

years hence, and the Canadian president is saying, "We must have a big

personnel integration program and totally reorganize the whole show." And

the American president says, "Say, who do you think you're talking to,

white boy?" That is a grievance joke with sort of a double barrel. Humor

is a profound area of research and social science because it shifts

around with the shifting area of sensitivity and grievance. Slang too is

very sensitively responsive to pressures in the environment and thus it

doesn't last long: when the pressure shifts, the slang disappears - it

fades out. Slang is a spontaneous and natural behavior which records

quite deep motivation. Slang, the grievance joke, and the joke without a

story line all belong to the electric world, where everything happens at

once.

The newspaper is like this. Any newspaper is crammed with events

in which there is no story line, no connection between any two events

except that which the reader may choose to make. There is a date line -

no story line. In an electric world the story line disappears quite

quickly like clothes lines, stag lines, party lies, hem lines, neck

lines. All forms of lineality disappear.

Television is a very nonlineal, nonstory-lie form as a medium.

Any story line that television has is borrowed from other media, like the

movie which has a natural story line. One of the effects, of course, of

the influence of television on the movie is that the Fellini world and

many of the new movies do not have a story line. The interchange of

influences between television and the movie has been extraordinary.

When television came in it went around the movie form and the

movie became an art form. The movie used to be vulgar trash; now it is

art. Whenever a new environment comes around an old environment, the old

environment becomes an art form: coach lamps, buggy wheels, and model-T's

anything. This applies at very high-brow levels. When the machine world

of railways and industry was new, it went around the old agricultural

world and turned it into poetry. The whole agrarian world became the

romantic movement, a great treasure and heritage. Meanwhile the new

mechanical world was abominated as monstrous. When electric circuitry

came in, it went around the mechanical world and turned the mechanical

world into an art form - abstract, nonrepresentative art. Whenever a new

environment appears it is spotted as the degrading and monstrous thing

and the old environment, which used to be degrading and monstrous,

becomes art. When will television become an art form? It is still

environmental. A simple answer is, of course, that television is not an

art form because there is nothing around it yet. There will be a moment

when television will become an art form and everyone will recognize it

and realize that it is a great art medium.

The western world organizes itself visually by connective,

uniform, and continuous space. The oriental world, antithetically,

organizes everything by spaces, by distances between sounds and objects,

not by connection. I read the other day a bit of advice to American

businessmen confronting Japanese clients: when you sit down with your

client, state your business in just a simple phrase and then be silent.

Thirty-five or forty-five minutes may go by. Say nothing. Every moment of

silence is working for you, because your client is inwardly meditating

your problem, your capacity, your pattern. He is deriving huge

satisfaction from this inward meditation; if you were to make some

connection between your problem and something else, this would destroy

the whole show. The oriental works by interval, not by connection, and

that is why we think he is inscrutable. We cannot visualize what is

happening. And, in the electric world in which we now live, everything

occurs by instantaneous little intervals rather than by connections. We

are orientalizing ourselves at a furious clip. The western world is going

east much faster than the eastern world is going west. The confusion this

creates is reminiscent of the Hieronymus Bosch problem. We all see how

the eastern world is acquiring some of our old nineteenth-century

technology - tractors and such - but it is not nearly so obvious to us

why we should be going east. We cannot perceive our own oriental drift

because it is so environmental as to be invisible. We do perceive their

western drift, on the other hand, and it does not make us very happy. We

figure they must be rivals and so we must deal with them as with any

other rivals - crush them. For ourselves, however, we wouldn't know how

to prescribe for an illness or distemper such as orientalism in our own

midst. It is like Alice in Wonderland. Alice was in a world where no

visual values existed, where there were no connections and no ground

rules she had ever heard of.

This kind of world has recently been looked into by Edward T.

Hall in a really fascinating and relevant book called Hidden Dimension.

Mr. Hall looks at space as it relates us to one another in social life

and in entertainment. He has spent a good many years studying the

distances which people in different cultures use between themselves in

conversation. For example, there is a space used in North America between

people that makes it very difficult for husbands to know the color of

their wives' eyes. If you ask one of them suddenly, "What is the color of

your wife's eyes?" the chances are he won't know. Now, this has something

to do with space. Hall has especially noticed that the space used in Arab

countries for conversation never exceeds eight inches, the reason being

that the Arab must be able to smell the person he is speaking to in order

to feel at ease or friendly. If he is unable to smell his interlocutor he

at once senses hostility. Hall tells this story. "I was sitting in a

hotel lobby in Chicago watching an elevator for a friend to emerge when I

suddenly became aware of a strange presence beside me. And this presence

kept sort of crowding and being somewhat oppressive and boorish and

obnoxious. And I was determined," he said, "not to heed this character

and not to be upset until suddenly he was joined by a group of friends

and I realized with a sigh of relief they were Arabs." Now, he said, "In

an Arab country any sitting person, any stationary person is fair game.

You shoot 'em down. Whereas a moving person, as in a motor car or on

foot, is sacrosanct, inviolate. You wouldn't dare interfere with a moving

object." In America, if you are sitting still, minding your own business,

you are inviolate. No one is going to bother you.

Every new medium changes our whole sense of spacial orientation.

Since television, our kids have moved into the book. They now read five

inches away from the book; they try to get inside it. Television has

changed their whole special orientation to one another and to their world.

If I were to ask the television industry, "What is the business

you are really in?" the answer would have to be, "We are in the business

of reprogramming the sensory life of North America, changing the entire

outlook and experience of the population." This has nothing to do with

programs; it has everything to do with the medium. For example,

television as a medium is a total antithesis of the movie. In the movie

you sit and look at the screen. You are the camera eye. In television you

are the screen. You are the vanishing point as in an oriental picture.

The pictures goes inside you. In the movie, you go outside into the

world. In television you go inside yourself. The television form of

experience is profoundly and subliminally introverting, an inward depth,

meditative, oriental. The television child is a profoundly orientalized

being. And he will not accept goals as objects in the world to pursue. He

will accept a role, but he will not accept a goal. He goes inward. No

greater revolution has ever occurred to western man or any other society

in so short a time. This profound revolution of sensibility and

experience came without warning. No one has even noticed that it has

happened and the effects of it have created all sorts of discomfort and

perturbation and all sorts of questions from the press, but no

understanding. The person who sits in front of a television image is

covered with all those little dots; all the light charges at him and goes

inside him, wraps around him and he becomes "lord of the flies."

Let us contrast this; let us go back for a moment to what

happened to us long ago. There was a time in the Greek world when western

man was still tribal and still lived almost entirely by ear in the

Homeric and Hesiodic world of poetry. There is a wonderful book on this

one, too, called Preface to Plato by Eric Havelock, in which he describes

this transition from the world of the ear to the world of the eye. He got

on to this idea of oral versus written culture during his acquaintance

with Harold Innis while teaching in Toronto at Victoria College. Havelock

is now head of classics at yale and is the first classicist to have

written on this subject as far as I know. The book is really concerned

with how people organized their experience before Plato, before writing,

and why Plato suddenly took off in the particular way he did in the

direction of classified knowledge and ideas instead of operational wisdom

of this Homeric type.

The modern connection of this subject is the detribalization,

which occurs in any society, and which is now going on in many parts of

the world by virtue and benefit of the phonetic alphabet. To detribalize

people, push up the visual component in their experience to a new

intensity and the ear component dims down. They become detribalized,

fragmented people. Owen Barfield has a book on this subject called Saving

the Appearances, in which he describes the effect of literacy in creating

modern civilized man with his values of detachment - objectivity. Before

the alphabet, ordinary society was profoundly involved in its experience.

Auditory man is always involved, he is never detached. He has no

objectivity. The only sense of our many senses that gives us detachment,

noninvolvement and objectivity is the visual sense. Touch is profoundly

involving; so are movement, taste, and hearing. All of these senses have

been given back to us by electric technology. Man is becoming once more

deeply involved with everybody.

When Oedipus set out the find "Who done it?" in his tribal

society, who performed this heinous thing that caused all the misfortune

to Thebes, he began a profound "James Bond" investigation into the

criminality of the offense, and he quickly discovered "I done it." One of

the peculiarities, you see, of a totally involved society is that

everyone is totally responsible. In an electric world you cannot isolate

responsibility, for many things may be relevant here. Everyone is so

involved in every aspect of everything because it all happens at the same

time, at the same moment, by the same technology.

In Truman Capote's book In Cold Blood, he describes a world of

involvement in which everybody is the murderer of those people, including

the author. If there is a real murderer, it is probably the author or the

reader, one or the other. No one seems to know. There is no question of

pinpointing and saying "He did it, I saw him. Get him. Punish him." Under

electric conditions of information it is impossible to say "He done it."

It used to be possible to say this under the old conditions of

nineteenth-century classification and fragmentation. You could pick out

the criminal and punish him, but under electric circuitry where

everything happens at once - impractical. It is a little like the change

in the dance floor. There used to be a time when people would dance

around in a space doing fox trots and waltzes. On the new dance floor

this doesn't happen. Space has changed. You couldn't ask anybody doing a

frug or a watusi for the next dance or for any dance. The dancers make

their own space, their own world. They do not share it with anyone and

you could not share it with them. This is a new electronic space, which

the kids understand instinctively and are miming and dancing. It isn't

necessarily bad. It is just so different from anything we have ever

known. It is nonwestern. It is noncivilized. It is nonhuman. But it is

valid. The electric world has its own ground rules and belongs to our

technology - technology which we have made ourselves. All of the

technologies that create these new environments are ones which we make.

Now this brings us back another step to the difference between

the public and the mass. You hear the word mass used a great deal in our

world. It is like the difference between the fox-trot floor and the

frug-dancing space. The public is a world in which everybody has a little

point of view and a little fragment of space all his own, private. In the

mass audience everyone is involved in everybody and there is no

fragmentation and no point of view. The mass is a factor of speed, not of

quantity. This is literally and technically true. The mass is created by

speed and everyone reading the same thing or doing the same thing at the

same time. It is like Einstein's idea that any kind or particle of matter

can acquire infinite mass at the speed of light. Any minute, trite bits

of news acquires infinite potential at the speed of electricity. Anything

becomes momentous at electric speeds. And a mass audience is an audience

in which everyone experiences and participates with everybody and in

which nobody has a private identity. So the psychiatrist's couches today

are groaning with the weight of people asking, "Who am I? Please tell me

who I am." There is no identity left. At electric speeds nobody has a

private identity. Don't ask whether this is good or bad. It is an

inevitable function of electric speeds. Now I don't think that we have to

be all that helpless; we can do something about it, if we are determined.

The public, or la publique as Montaign called it, came into

existence in the sixteenth century with typography. It never existed in

the Middle Ages and it no longer exists today. Under electric conditions

there is no public. There is a mass, meaning everyone involved. How does

one conduct oneself in the midst of a mass of totally involved and

metaphysically merged entities? Nobody ever asked this question. I

personally don't find any satisfaction in complaining about it, or in

congratulating ourselves upon it. This is one of those things that really

happens: it is a happening. Many people, by comparing or contrasting it

with some other condition, in some other part of the world or in some

other time in our own world, may or may not take satisfaction in it, but

I personally see no basis for that. Montaigne was the first person to

discover la publique, and he was also the first person to discover

self-expression. He said in one of his essays, "I owe the public a

complete portrait of myself." As soon as the public exists, the author

exists. Until the author exists the public does not exist. They make each

other. So, when Montaigne discovered the public, he discovered

self-expression at the same moment.

Today self-expression is meaningless because there is no public.

There is only the mass. Anyone who attempts to attach artistic importance

to self-expression is talking back in the sixteenth or the nineteenth

centuries and not about our time. The whole complaint about elite art

versus mass art is irrelevant because it ignores the technologies in

question. Advertising can be regarded as a profoundly important art form,

but it is not private self- expression. The newspaper is a profoundly

important form of expression, but it's not self- expression. Take the

date line off a newspaper and it becomes an exotic and fascinating

surrealist poem. The old idea of elite art, which is now obsolete or

useless, was that it was a storehouse of values, of self-expression and

self-discovery, of great moments of individual experience stored up as in

a blood bank for the use of the community or of the privileged classes.

Today the whole idea of art is that it is an instrument of discovery and

perception: that real art, valuable art, offers you the means of

perception. Flaubert said, "Style, it is a way of seeing." It is not a

form of self-expression. Conrad said of his whole life's work, "It is

above all that you may see...That's why I made it." This is the technique

of perception. Art is not a consumer commodity. It is not a package, as

it may have been in the nineteenth century. Art is now a way of seeing,

of knowing, of experiencing a world, of exploring the universe - like

science. The difference between art and science ceased in 1850 with

Cezanne. Art, just as much as science, became a technique of

investigation and exploration of the universe with Cezanne, Bioleau, and

Flaubert.

Now, how does one relate art to new media, to television? What is

the future of art in relation to such a form? Keep in mind that with

typography and the printed word the public came into existence for the

first time. Printing was a technique so powerful that it created la

publique. The manuscript, the handwritten book could not produce a

public, a reading public or a market for goods or anything else. With the

uniformly produced, repeatable, printed book came, for the first time, a

commodity with uniform pricing. Until this time, there was nothing ever

produced uniformly with a price on it, except perhaps gold or bronze

coins. With the coming of the printed book you get the market and you get

the public, and television merges these two entities.

That backward or distant countries have difficulty in forming

markets or imitating our way of life need not be baffling. Indonesia or

India could not possibly have a pricing system until they have had long

centuries of our type of literacy and uniformity. Without our type of

uniformity you cannot say "this costs 39 cents." When you say to an

Indian or an Arab, "This costs so much, it's a fixed price," he simply

considers this a challenge to his dramatic ability. And so if you try to

say, "But look, t his is the price and has nothing to do with your desire

to dramatize your abilities," he will consider himself robbed, deprived,

degraded. Our pricing system degrades most countries: it robs and

impoverishes their whole way of life. And don't blame them for going into

Communism. Communism is the only possible out, just as the PX store is

the only possible out for people hurrying into uniform production.

Backward countries don't approach Communism as an ideal, they regard it

as the only possible means of mechanizing. In this regard, keep in mind

that when a new technology goes around an old society the society tends

to idealize its old technology - for example when Russia got our western

machine world, this drove them back into a furious idealization of their

primitivism. So you can depend on it. China will have suddenly emerging

within its borders a huge idealistic movement to glorify the ancient

China and to downgrade and stamp out all western forms. This is

inevitable. We did it to ourselves over and over again, and every country

that ever got a new technology always built up an ideal out of the old

one. The Romans idealized the Greeks, the Greeks had ideals of

spontaneity and barbarism. The Middle Ages idealized the Romans. the

Renaissance idealized the Middle Ages - witness Don Quixote - and the

eighteenth century idealized the Renaissance. We idealize the nineteenth

century. That's our image - Bonanza.

Another hypothesis of mine is that Batman is a nostalgia for the

world of fifteen-year- old experience, a nostalgia produced by color

television. Color television is a new environment producing nostalgia for

an old one. The old one is comic books. The year of the first comic book

in North America was 1935. So we are due for a little nostalgic revival

thanks to color television. Color television is also a new technology

going around the old black-white. It creates a new experience in our

world and will change the whole sensory life of North America. Color

television will have many of the effects that color has on other peoples:

for instance it will encourage them to cultivate very hot spiced foods.

Color television is a world that effects all the senses, not some of the

senses: it is not just a visual form. It will change our sense of hearing

as well as our sense of taste and our outlook. It's quite easy, once you

know the components of a new technology, to pin-point certain

developmental results in a given culture. The effect of color television,

for example, in India would be quite different from its effect in North

America. It is just the same with radio. Taking radio into Algeria has a

very different effect from taking it into England. In England the

auditory sense is stepped up to a new intensity in a culture that is

highly literate and this has a very different effect from stepping up the

auditory sense in a culture that is almost totally auditory, like North

Africa. Television has had a very different effect on France from what it

has had on us. It has Americanized France; it has Europeanized us.

Television has downgraded our visual life and values to the point of

rigor mortis. It has cooled us off the point almost of rigor mortis

politically. On the other hand, television has heated up the French, who

are not as visual as we. French television, by the way, has an 819 line

picture definition as compared to our 525 line definition. If we used 819

lines, this would help us out of a lot of nasty school problems, right

now. Our kids would find school easier because if the visual photographic

level of the medium were pushed up a bit, there would be a bridge between

their electric world and their school room which would ease their

problems. I suggest this hypothetically. But there are many reasons for

saying that it is almost certainly true.

Another basic fact about our electric environment: it creates a

total environment like the world of the hunter. Man entered the phase of

neolithic or specialized sedentary life 10 thousand years or more ago. He

sat down and began to specialize and weave baskets, make pots, and grow

crops, and domesticate animals. For many, many ages before that he had

been a hunter. With electronic technology man becomes a hunter again.

Hence James Bond, hence the sleuth, hence crime. Crime in our program

world has nothing to do with television as such. It has very much to do

with the fact that electronically the whole world becomes a hunting

ground for information, data. Modern man is the hunter, and crime and the

sleuth are natural modalities of the recovery of his ancient status. The

specialist man, the classifier, is not at home in the electronic world.

The electronic world rubs out all barriers, all partitions, all

classifications. That is why the existentialist discovers the difficulty

of having a personality in the modern world. Electrically, you cannot

have a private personality. It belongs to an older technology of data

classification: for example, "I'm a Hungarian, I'm a dentist, I'm 35, I

have three kids, that's me." Under electric conditions that's nobody!

People have trouble orienting themselves in this new environment because

no one told them that it has new ground rules; the ground rules are

always invisible anyway. So, the world of the hunter - our world; the

nineteenth century - the world of the planter. In our type of world, the

programming of the sensor environment becomes the normal activity of men.

At the Center, over the last three or four years, we have been

working on a project called a "Sensory Profile" of the entire Toronto

population. We have devised, by the most approved and fragmented and

quantitative social science procedures, a means of discovering what are

the sensory preferences of the entire Toronto population. Through the

speed of learning of our subjects, we have discovered how long it takes

them to recognize a visual, auditory, tactile, kinetic pattern within the

same pattern. With all these different sensory ways tied to computer

measuring devices, we have been able to profile their whole sensory life

and preferences and also the changes in that life over the past thirty

years. So we are in a very good position to tell you exactly what

happened to the sensory life of the Toronto population when television

came in. We would like to do this study in many other parts of the world,

because I am pretty sure it is an indispensable resource for decision

makers in every field. We would like to do it in Greece before they get

television and then afterwards. We would also like to test the effects of

other forms on the sensory lives of people of other countries.

Once you know the sensory profile of a people, how much intensity

they allow to their visual life or their auditory life, you can just read

it off as a a percentage of their whole sensorium. Then you can exactly

program the entertainment, or clothing, or colors, or food, or anything

for that area. You know exactly what is wanted. While this is neither

good nor bad, it might terrify some people. They are going to say, "Who

is going to decide?" This reaction is based upon the old technology of

fragmentation and specialism.

When this kind of knowledge comes in, people automatically assume

new responsibilities. New technologies create new roles and new

responsibilities. People respond to these, as our children are doing.

Jacques Ellul, in a wonderful book called Propaganda, mentions somewhere,

on a page or so, that in the whole history of mankind no child ever

worked as hard as the twentieth-century child - data processing. The

amount of information overload in the environment of the child today is

fantastic. No human being ever had to contend with such amounts of

information as a daily load for processing. Every one of our children

engages in a data-processing load that is overwhelming by any human

standards. So what do they do? They find short cuts. Our children become

mythic in their whole structuring of reality. Instead of classifying

data, they make myths. It is the only possible way of coping with the

overload.

IBM were the first people who asked themselves the question,

"What is the business we're really in?" They began to look into it and

they came up first with negative answers and said, "Well, whatever it is

we are not in the business of making business machines. That's not our

business." Further study, much further study, and they came up with this

answer: "We are in the business of data processing. It doesn't matter by

what means, that's our business." So, ever since then they have just gone

like a shot because they have not been worried about the particular

technology they're using. They know that data processing is permanent and

it doesn't matter what technology is used - an abacus will do just as

well as nose counting. They added one other thing - "We are in the

business of pattern recognition." That's their pet phrase and I think

this is the business that we are all in - the business of an electric

society is pattern recognition. Now in regard to a normal activity like

instruction or education, if you were to ask a teacher, an ordinary

person, "What is the business you are in?" he would say instruction;

instructing the young. He would be wrong. The business of teaching is to

save students' time, not to instruct them. Anyone can learn anything if

he has enough time. It's the same with the doctor. A doctor's job or a

hospital's job is not to cure people. It's to cure people much faster

than they would otherwise get well. It's to save the patients' time. When

you know your business, it saves a lot of headaches and a lot of

confusion. And I'm pretty sure that when we realize that a new technology

completely alters the sensory life of a whole population, we realize that

the business of most of us is reprogramming the sensory life of the

population. And when we know this, it creates a new kind of responsibility.

I've often been struck on the west coast by a strange behavioral

pattern or personal life style which I try to explain to myself by

saying, "Well, this is a part of the world that never had a nineteenth

century." There was no big metropolitan industrial time of highly

specialized activities with heavy industry and so on. You could say then

that the people in the west coast area leap-frogged out of the eighteenth

into the twentieth century, skipping the nineteenth. This is a big

advantage. The nineteenth century was the period of maximal fragmentation

and classification. People who leap-frogged out of the eighteenth into

the twentieth century are more imaginative, more flexible, more

perceptive than those who went through the nineteenth. The nineteenth

century was a gristmill that really broke people into little bits. On the

other hand it created many values that do not exist on the west coast -

privacy, separateness, neatness, order of all sorts of visual kinds. You

can see that the environment of parts of California is a tribute to the

eighteenth-century imaginative life. No nineteenth-century mind would

tolerate the environment of country left in its natural state.

Nineteenth-century man would tidy up the trees and the tree trunks. He

would level the whole terrain. He would give it the good old steam-roller

treatment. That was the nineteenth century - the century of the iron horse.

The safety car is an extraordinary indiction of the new mood in

America. It's the end of an era. The safety car is a way of saying,

"Look, we're not just interested in the engineering job here. We want to

know, what does it do to people? What's the effect it has on the people?"

And the effect is then built into the car. It is like the safety pin. A

safety pin is made by folding the thing back into itself and clasping it;

that is how the safety car will be made. Instead of just pointing it out

at an environment, you fold it back into itself and clasp it. The safety

car is a revolution. Are we ever going to get any safety media or safety

science?

The future of commercial television raises the theme of the

future of a good many things, including advertising. A student at the

Center wrote a paper for me the other day on the future of advertising,

pointing out that it has already got the future written all over it.

Advertising is substituting for product, because the consumer today gets

his satisfaction from the ad, not the product. This is only beginning.

More and more the satisfaction and the meaning of all life will come from

the ad and not from the product. In an information environment - the

electric light creates an information environment, so does television -

the service industries take over from hardware and products. The service

industries are all informational, like advertising. The future of

advertising on television is huge because it has to take on the whole job

of giving you the product and the effects of the product. Advertising

will be participation in the products, understanding and use and

satisfaction from them. So the future of commercial television has a

whole series of questions tied up in it. Don't try to hold it fixed in

front of you, and continue to look at it as if it were going to stay

fixed. Television will change totally, just as advertising is going to

change, just as work is changing. Work is becoming learning and knowing

rather than repetitive job holding.

The book, for example, under xerography, is taking on a totally

different character from the printed book. Xerography means applying

electric circuitry to an old mechanical process. With xerography the

reader becomes a publisher and printer and author. Any school- teacher

can publish her own text for her own class, by taking a page out of this

and a chapter out of that and handing it out. The publishers know this

and they are panicking. Circuitry means a total revolution in the book -

the book becomes a service. Instead of being a package, uniform and

repeatable, the book becomes a service to suit the needs of the private

person. Each book becomes a work of art, a private production. Even now

in Toronto, you can phone the electric information service and say, "I'm

working on Egyptian arithmetic and I know a little Arabic and I know a

little French; I know a little this and that. Please send me the latest."

And they will whisk off a batch of pages and cards to you, Xeroxed and

reproduced from all the latest journals in all the countries of the

world. It's a service for the schools. So the book, as a package

uniformly, repeatably produced is not in electric technology. On the

other hand, its being obsolescent doesn't at all mean that it's going to

disappear, it just means that the book will no longer set the ground rules.

That's the future of television. With cheap playback and video

playback and so on, the future of television will be very much like that

of the disc, the LP. Movies will be the same. The future of television

also relates to the Laser ray and putting the image in multidimension in

the middle of the room instead of on a panel and so on.

The future of commercial television really contains thirty or

forty different questions, the commercial one being one of the most

illusive because commerce in our world now just means information.

Management also is just an information service; it is part of the service

industries. Decision making is based entirely on information, and so is

medicine. Commerce in our world is taking on more and more of the

abstract character of information. The future of commercial television

combines the whole lot of marriages of technologies.

Now, I will hazard a guess about the future of the planet. It is

not quite as harrowing as you might suppose. When satellites and electric

information went around the planet, they created a man-made environment

around the planet which ended the planet as a human habitat and turned it

into the content of the man-made environment. The same thing will now

happen to the planet that's happened to every other environment when it

becomes the content of a new environment. It will become an art form. The

future of the planet is camp, an old nose cone. You know the story about

the two mice in the nose cone. One says to the other, "Hey, how do you

like this kind of work?" And the other one says, "Oh, well, I guess it's

better than cancer research." The planet as art form is going to get the

Williamsburg treatment. All the old nooks and crannies of the planet that

used to house strange or interesting phenomena and human behavior will be

reconstructed faithfully, archaeologically, and tenderly. The planet will

be dealt with as a work of art, you know, where the whole human

enterprise began. People will come back from other parts of the world,

other parts of the universe to have a look at Plymouth Rock, which should

have landed on the Pilgrims, as Stevenson said. And the planet is going

to become an old nose cone, an old hunk of camp, an old work of art; and

that then is the answer to television. With satellites, television ceases

to be environmental and becomes content, becomes art form. As long as it

has environmental power it is invisible, and as we notice only those

characteristics of it which belong to the old technology, movies. When

television becomes an old technology, we will really understand and

appreciate its glorious properties.

"Television in a New Light" in The Meaning of Commercial Television -

Stanley T. Donner, ed., University of Texas Press, 1966, pp. 87-107.

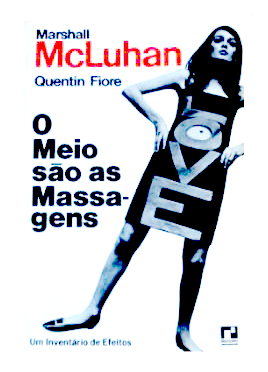

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment