skip to main |

skip to sidebar

cage

Prefatory note by George Sanderson.

Eric McLuhan has forwarded this piece which he wrote

with Marshall. It was also a favorite of John Cage.

Eric remarks "The title comes from the medieval idea

of Agenbite of Inwit -- remorse of conscience. We

liked the "bite" idea and the link between out-wit,

outering of wits, and extensions of man."

The Agenbite of Outwit

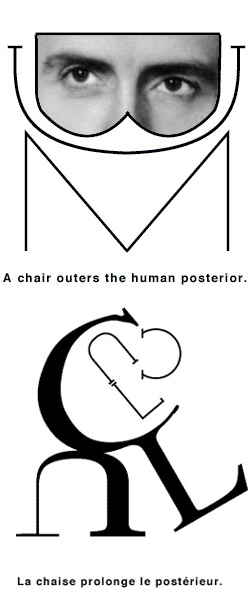

With the telegraph Western man began a process of

putting his nerves outside his body. Previous technologies

had been extensions of physical organs: the wheel is a put-

ting-outside-ourselves of the feet; the city wall is a col-

lective outering of the skin. But electronic media are, in-

stead, extensions of the central nervous system, an inclusive

and simultaneous field. Since the telegraph we have extended

the brains and nerves of man around the globe. As a result,

the electronic age endures a total uneasiness, as of a man

wearing his skull inside and his brain outside. We have be-

come peculiarly vulnerable. The year of the establishment of

the commercial telegraph in America, 1844, was also the year

Kierkegaard published The Concept of Dread.

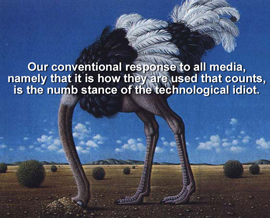

A special property of all social extensions of the

body is that they return to plague the inventors in a kind of

agenbite of outwit. As Narcissus fell in love with an outering

(projection, extension) of himself, man seems invariably to

fall in love with the newest gadget or gimmick that is merely

an extension of his own body. Driving a car or watching

television, we tend to forget that what we have to do with is

simply a part of ourselves stuck out there. Thus disposed, we

become servo-mechanisms of our contrivances, responding to them

in the immediate, mechanical way that they demand of us. The

point of the Narcissus myth is not that people are prone to

fall in love with their own images but that people fall in love

with extensions of themselves which they are convinced are not

extensions of themselves. This provides, I think, a fairly good

image of all of our technologies, and it directs us towards a

basic issue, the idolatry of technology as involving a psychic

numbness.

Every generation poised on the edge of a massive change

seems, to later observers, to have been oblivious of the issues

and the imminent event. But it is necessary to understand the

power of technologies to isolate the senses and thus to hypno-

tize society. The formula for hypnosis is "one sense at a time."

Our private senses are not closed systems but are endlessly

translated into one another in the synesthetic experience

we call consciousness. Our extended senses, tools, or tech-

nologies, have been closed systems incapable of interplay.

Every new technology diminishes sense interplay and awareness

for precisely the area ministered to by that technology: a

kind of identification of viewer and object occurs. This

conforming of the beholder to the new form or structure

renders those most deeply immersed in a revolution the least

aware of its dynamic. At such times it is felt that the fu-

ture will be a larger or greatly improved version of the

immediate past.

The new electronic technology, however, is not a

closed system. As an extension of the central nervous system,

it deals precisely in awareness, interplay and dialogue. In the

electronic age, the very instantaneous nature of the co-exis-

tence among our technological instruments has created a crisis

quite new in human history. Our extended faculties and senses

now constitute a single field of experience which demands that

they become collectively conscious, like the central nervous

system itself. Fragmentation and specialization, features of

mechanism, are absent.

To the extent that we are unaware of the nature of

the new electronic forms, we are manipulated by them. Let me

offer, as an example of the way in which a new technology can

transform institutions and modes of procedure, a bit of

testimony by Albert Speer, German armaments minister in 1942,

at the Nuremberg trials:

The telephone, the teleprinter and the wireless made it

possible for orders from the highest levels to be given

directly to the lowest levels, where, on account of the

absolute authority behind them, they were carried out

uncrtitically; or brought it about that numerous offices

and command centers were directly connected with the su-

preme leadership from which they received their sinister

orders without any intermediary; or resulted in the wide-

spread surveillance of the citizen; or in a high degree of

secrecy surrounding criminal happenings. To the outside ob-

server this governmental apparatus may have resembled the

apparently chaotic confusion of lines at a telephone ex-

change, but like the latter it could be controlled and op-

erated from one central source. Former dictatorships need-

ed collaborators of high quality even in the lower levels

of leadership, men who could think and act independently.

In the era of modern technique an authoritarian system can

do without this. The means of communi cation alone permit

it to mechanize the work of subordinate leadership. As a

consequence a new type develops: the uncritical recipient

of orders.

Television and radio are immense extension of ourselves

which enable us to participate in one another's lives, much as

a language does. But the modes of participation are already

built into the technology; these new languages have their own

grammars.

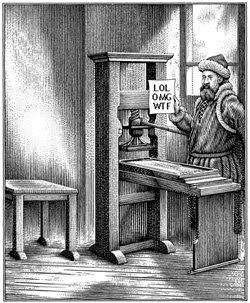

The ways of thinking implanted by electronic culture

are very different from those fostered by print culture. Since

the Renaissance most methods and procedures have strongly tended

towards stress on the visual organization and application of know-

ledge. The assumptions latent in typographic segmentation manifest

themselves in the fragmentation of crafts and the specializing of

social tasks. Literacy stresses lineality, a one-thing-at-a-time

awareness and mode of procedure. From it derive the assembly line

and the order of battle, the managerial hierarchy and the depart-

mentalizations of scholarly decorum. Gutenberg gave us analysis

and explosion. By fragmenting the field of perception and infor-

mation into static bits, we have accomplished wonders.

But electronic media proceed differently. Television,

radio and the newspaper (at the point where it was linked with

the telegraph) deal in auditory space, by which I mean that

sphere of simultaneous relations created by the act of hearing.

We hear from all directions at once; this creates a unique,

unvisualizable space. The all-at-once-ness of auditory space is

the exact opposite of lineality, of taking one thing at a time.

It is very confusing to learn that the mosaic of a newspaper

page is "auditory" in basic structure. This, however, is only

to say that any pattern in which the components co-exist with-

out direct, lineal hook-up or connection, creating a field

of simultaneous relations, is auditory, even though some of

its aspects can be seen. The items of news and advertising that

exist under a newspaper dateline are interrelated only by that

dateline. They have no interconnection of logic or statement.

Yet they form a mosaic of corporate image whose parts are

interpenetrating. Such is also the kind of order that tends to

exist in a city or a culture. It is a kind of orchestral, reson-

ating unity, not the unity of logical discourse.

The tribalizing power of the new electronic media,

the way in which they return us to the unified fields of the

old oral cultures, to tribal cohesion and pre-individualist

patterns of thought, is little understood. Tribalism is the

sense of the deep bond of family, the closed society as the

norm of community. Literacy, the visual technology, dissolved

the tribal magic by means of its stress on fragmentation and

specialization, and created the individual. The electronic

media, however, are group forms. Post-literate man's elec-

tronic media contract the world to a tribe or village where

everything happens to everyone at the same time: everyone

knows about, and therefore participates in, everything that

is happening the moment it happens. Because we do not under-

stand these things, because of the numbing power of the tech-

nology itself, we are helpless while undergoing a revolution

in our North American sense-lives, via the television image.

It is a change comparable to that experienced by Europeans in

the 'twenties and 'thirties, when the new radio image recon-

stituted overnight the tribal character long absent from

European life. Our extremely visual world had immunity from

the radio image, but not from the scanning finger of the TV

mosaic.

It would be hard to imagine a state of confusion

greater than our own. Literacy gave us an eye for an ear and

succeeded in detribalizing that portion of mankind that we

refer to as the Western world. We are now engaged in an accel-

erated program of detribalization of all backward parts of the

world by introducing there our own ancient print technology at

the same time that we are engaged in retribalizing ourselves

by means of the new electronic technology. It is like becoming

conscious of the unconscious, and of consciously promoting un-

conscious values by an ever clearer consciousness.

When we pout our central nervous system outside us we

returned to the primal nomadic state. We have become like the

most primitive paleolithic man, once more global wanderers, but

information gatherers rather than food gatherers. From now on

the source of food, wealth and life itself will be information.

The transforming of this information into products is now a

problem for the automation experts, no longer a matter for the

utmost division of human labour and skill. Automation, as we

all know, dispenses with personnel. This terrifies mechanical

man because he does not know what to do about the transition,

but it simply means that work is finished, over and done with.

The concept of work is closely allied to that of specialization,

of special functions and non-involvement; before specialization

there was no work. Man in the future will not work; automation

will work for him, but he may be totally involved as a painter

is, or as a thinker is, or as a poet is. Man works when he is

partially involved. When he is totally involved, he is at play

or at leisure.

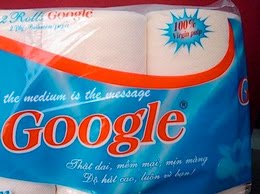

Man in the electronic age has no possible environment

except the globe and no possible occupation except information-

gathering. By simply moving information and brushing information

against information, any medium whatever creates vast wealth.

The richest corporation in the world -- Atlantic Telephone and

Telegraph -- has only one function: moving information about.

Simply by talking to one another, we create wealth. Any child

watching a TV show should be paid because he or she is creating

wealth for the community. But this wealth is not money. Money

is obsolete because it stores work (and work, and jobs, are

themselves obsolete, as we see daily). In a workless, non-spe-

cialist society, money is useless. What we need is a credit

card, which is information.

When new technologies impose themselves on societies

long habituated to older technologies, anxieties of all kinds

result. Our electronic world now calls for a unified field of

global awareness; the kind of private consciousness appropriate

to literate man can be viewed as an unbearable kink in the

collective consciousness demanded by electronic information

movement. In this impasse, suspension of all automatic reflexes

would seem to be in order. I believe that artists, in all media,

respond soonest to the challenges of new pressures. I would like

to suggest that they also show us ways of living with new tech-

nology without destroying earlier forms and achievements. The

new media, too, are not toys; they should no be in the hands of

Mother Goose and Peter Pan executives. They can be entrusted

only to new artists.

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)