![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

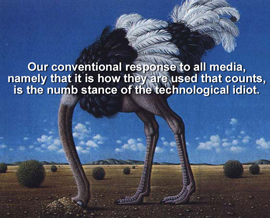

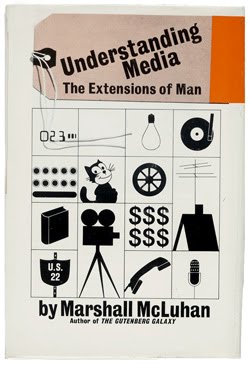

Literally, Understanding Media is a kit of tools for analysis and perception. It is to begin an operation of discovery. It is not the completed work of discovery. It is intended for practical use. Most of my work in the media is like that of a safecracker. In the beginning I don’t know what’s inside. I just set myself down in front of the problem and begin to work. I grope, I probe, I listen, I test — until the tumblers fall and I’m in. That’s the way I work with all these media.

I’m perfectly prepared to scrap any statement I ever made about any subject once I find that it isn’t getting me into the problem. I have no devotion to any of my probes as if they were sacred opinions. I have no proprietary interest in my ideas and no pride of authorship as such. You have to push any idea to an extreme, you have to probe. Exaggeration, in the sense of hyperbole, is a major artistic device in all modes of art. No painter, no musician ever did anything without extreme exaggeration of a form or a mode, until he had exaggerated those qualities that interested him.

- McLuhan Hot + Cool, Stearn, 1967: 58, 62-63

Stan Lee : " DON’T WRITE DOWN TO YOUR READERS! It is common knowledge that a large portion of comic magazine readers are adults, and the rest of the readers who may be kids are pretty sharp characters. They are used to seeing movies and listening to radio shows… a great deal of thought goes into every story; and there are plenty of gimmicks, sub-plots, human interest angles…. "

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

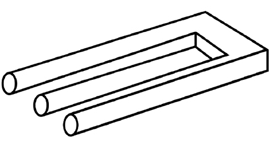

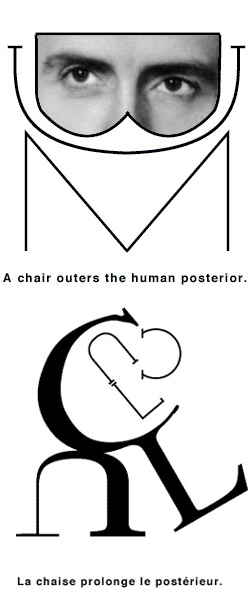

All situations are composed of an area of attention [figure] and a very much larger (subliminal) area of inattention [ground] ….Figures rise out of, and recede back into, ground….for example, at a lecture, the attention will shift from the speaker’s words to his gestures, to the hum of the lighting or street sounds, or to the feel of the chair or a memory or association or smell, each new figure alternatively displaces the others into ground…The ground of any technology is both the situation that gives rise to it as well as the whole environment (medium) of services and disservices that the technology brings with it. These are side effects and impose themselves willy-nilly as a new form of culture.

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

"Don't tell me what's in the books. I've read them. Tell me what you've learned that you didn't already know.Then, we may both learn something new."

But I've never presented such explorations as revealed truth. As an investigator, I have no fixed point of view, no commitment to any theory -- my own or anyone else's. As a matter of fact, I'm completely ready to junk any statement I've ever made about any subject if events don't bear me out, or if I discover it isn't contributing to an understanding of the problem. The better part of my work on media is actually somewhat like a safe-cracker's. I don't know what's inside; maybe it's nothing. I just sit down and start to work. I grope, I listen, I test, I accept and discard; I try out different sequences -- until the tumblers fall and the doors spring open.

2 comments:

Bursting Into That Silent Sea by Geritol Fialkaseltzer 1-07

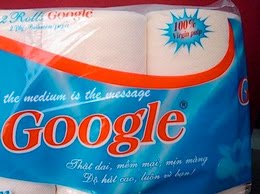

Marshall McLuhan's tsunami of writings and dialogues from 1940 to 1980 not only canaried the coalmines, but also parroted Poe, Pound and Plato's cyberspace-is-the-place cave dwellers. His thunderclouds still downpour. He recognized that the Great American Novel was/is the newspaper, the TV, the Internet and what follows next.

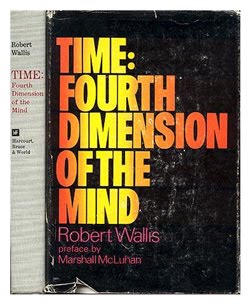

McLuhan's probes and percepts spawned the books of Richard Cavell, Robert Dobbs, Janine Marchessault, Eric McLuhan, Don Theall, and Frank Zingrone. Their reach exceeds their grasp. By practicing media yoga, these authors inaugurate early radar systems and rearview mirrors detecting how the major transformations in technology affect us. They have "applied McLuhan" to promote mapmakers searching for new lands and new data.

These Finneganese McLuhanites daze the doubleness, figure the ground and cliche the archetypes. Raised on Mad Magazine, they juggle Alfred E. Newman's observation that the English language is the only one where a double negative is a no-no. These safecrackin' authors navigate the deluge of McLuhan epiphanies, including:

1) McLuhan teases people into believing his percepts were theories.

2) Artists are engaged in writing a detailed history of the future because they are the only people who live in the present. All-at-onceness?

3) Artists are the antennae of the race. Their distant early warnings can broadcast ways to cope with media's hidden environments.

4) The effects of the artist's work precede the causes, like Poe's reasoning backwards which influenced the Symbolists.

5) The opposite of a great truth may not be falsity. It may be another great truth.

6) Effects are narcotic.

7) McLuhan's whirlpool of new questions spawn more: What is percept-plunder for the recent future? What simultaneities are double-duty interrobanging the cultural numbing process? Oops, there goes another phantom cellphone vibration?

In particular, Robert Dobbs' better beyonds swell in paramedia multi-consciousness. He hoicks up McLuhan's converting to Catholicism as performance art. He upgrades Andy Warhol to "in the future everyone will have privacy for 15 minutes." Dobbs delights in words evoking more than their meanings, as we say "dot com" daily and neglect the prospect that the "com" could be "communism." He pranks the pranksters with dis disinformation (spy vs spy vs spy). He reincarnates McLuhan's "Pollstergeist" as the Android Meme (humans imitating the effects of what we invent). Dobbs expands McLuhan's "the radio caused World War II" to "the cellphone caused 9/11." I wanna holler but the global theater is too small.

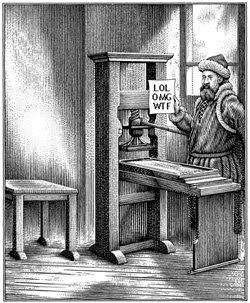

Dobbs takes it beyond, as did Frank Zappa, who astutely inquired about the identity of the brain police. Are they the hidden effects of what humans invent, or are they those creating diseases and offering cures? Marshall McLuhan, who applied James Joyce's FINNEGANS WAKE to reveal these invisible environments, perceived that we shape our tools, then they shape us. McLuhan swirled in Zappa's question like Poe's Maelstrom sailor. If one recognizes patterns, then the resulting comprehensive awareness may prevent drowning in somnambulism? One can manipulate Menippean satire (double irony) into making, matching and "take it" beyond.

Standing on the shoulders of these giants, I assert the importance of questioning that shakes people out of their reality tunnels. I continue to be drenched by these inventors of new metaphors asking what is a meta for? The sky is crying, look at the laughtears roll down its facebook. I have a beef in my heart. The Captain counterblasts "Big dig infinity," and they bugged it. Pull the medium over your own mess-age. "How are you to argue with people who insist on sticking their heads in the invisible teeth of technology, calling the whole thing freedom?" - McLuhan.

-This long lost document surfaced on The Ides of March, 1953 when subgenius researchers discovered the British secret police had investigated Joyce's FINNEGANS WAKE in hopes to find the origins of MK-ULTRA mind control experiments. Their studies also may have exposed roots of the complex clairvoyance of conceptual continuity, handsignals for the blind Masons and/or the faux faux documenting of Colonel Baldwin's 99 lufta-tribulations.

Finnegans Wake (1939), a novel by James Joyce written in a highly innovative ‘dream-language’ combining multilingual puns with the stream-of-consciousness technique developed in Ulysses.

The title is taken from an Irish-American ballad about Tim Finnegan, a drunken hod-carrier who dies in a fall from his ladder and is revived by a splash of whiskey at his wake.

It also suggests that Fionn mac Cumhaill will return to be punished once more for his recurrent sins.

The structure of the work is largely governed by Giambattista Vico's division of human history into three ages (divine, heroic, and human), to which Joyce added a section called the ‘Ricorso’, or return.

It also systematically reflects Giordano Bruno's theory that everything in nature is realized through interaction with its opposite. The central figures of the Wake are Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (HCE), Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP), Shem the Penman, Shaun the Post, and Issy—respectively the parents, sons, and daughter living at the Mullingar Inn in Chapelizod, Co. Dublin.

In a sense, however, these are not characters at all but aspects of the Dublin landscape, with the Hill of Howth and the River Liffey serving as underlying symbols for male and female in a world of flux.

Other recurrent characters are the four old men, collectively called Mamalujo and modelled on the four evangelists and also an apostolic group of twelve who feature as clients in the pub, or members of a jury.

The narrating voice of individual sections can generally be identified with one or other member of this polymorphous cast.

In ‘Shem the Penman’, the autobiographical section of the work, Joyce describes the work as an ‘epical forged cheque’ made up of ‘once current puns, quashed quotatoes, messes of mottage’.

The narrative line of Finnegans Wake consists of a series of situations relating to the sexual life of the Earwicker family.

HCE perpetrates a sexual misdemeanour in the Phoenix Park. ALP defends him in a letter written by Shem and carried by Shaun. The ‘litter’ is retrieved by a hen scratching in the midden. The boys endlessly contend for Issy's favours. HCE grows old and impotent, is buried, and revives. Aged ALP prepares to return as her daughter Issy to catch his eye again; and the book ends with an unfinished phrase (‘… along the’) flowing into the first words of the first paragraph (‘river-run …’).

Book I. ‘The Fall’ retells the story of Tim Finnegan against mythical and historical backgrounds ranging from the Tower of Babel to the Wall Street Crash.

Book II. ‘The Mime of Mick, Nick and the Maggies’ is a matinée performance in ‘the Feenicht's Playhouse’ based on children's games and full of Dublin theatrical lore. In ‘Night-lessons’ the children are at their homework studying a classroom textbook to which Shem and Shaun add rubrics in the margins. ‘Scene in the Pub’ features two television plays: ‘The Norwegian Captain’ is a love-story concerning a hunchback sailor and the daughter of a ship's chandler; the other, ‘How Buckley Shot the Russian General’ is based on a Crimean story told by Joyce's father. In ‘Mamalujo’ the romance of Tristan and Isolde is narrated by the four old men in the guise of seagulls hovering above the lovers' boat.

Book III. ‘The Four Watches of Shaun’ describes the passage of Shaun the Post along the Liffey in a barrel. Shaun's censorious attitude combines freely with a prurient interest in sexual matters. The ‘Yawn’ chapter is a seance or an inquisition. Lying at the centre of Ireland at the Hill of Uisneach in Co. Westmeath, Shaun reveals a treasure-trove of Irish culture whose contents are transmitted in a radio broadcast involving a welter of voices.

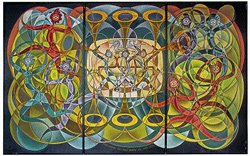

Book IV. The ‘Ricorso’ is a triptych with St Kevin and St Patrick in the side positions and St Laurence O'Toole at the centre. Anna Livia's letter defending HCE is given its fullest statement. The Wake ends with her soliloquy.

Joyce began Finnegans Wake in autumn 1922 by accumulating material in a notebook known as Buffalo Notebook. Many episodes appeared as separate publications between 1924 and 1932, during which time the book was known as ‘Work in Progress’ and its final title kept a secret. Joyce frequently compared the Wake to another complex Irish literary production, the Book of Kells. If Finnegans Wake is about creation on a theological scale, its characteristic amalgam of sadness and laughter marks it as a comic masterpiece.

Post a Comment