"information overload implodes into pattern recognition..."

"At the speed of light, objects are unobservable, only relationships and patterns among objects are observable ..."

TECHNOLOGY AND POLITICAL CHANGE

by H. M. McLuhan

“I know about the reasons for the revolution in Mexico," wrote Karel Capek,

"but I know nothing at all about the reasons for my next-door

neighbour's quarrels. This condition of the man of today is

called world citizenship, and it arises from reading the papers." This is to say,

among other things, that no matter how much technology

reduces the intellectual and social isolation of people, their metaphysical

isolation is little affected. But the speed with which we are today abridging

the intellectual isolation of people is unquestioned.

Bergson argued that if some cosmic jokester were to speed up the

entire universe we could detect the event by the impoverishment of

mind that would ensue. If only on a planetary scale, we are now in a

position to observe the effects of such accelerated operations

socially and intellectually, because modern communications have become

geared to the speed of light, and transportation is not too far behind.

It is perhaps useful to consider that any form of communication

written, spoken, or gestured has its own aesthetic mode, and that this

mode is part of what is said. Any kind of communication has a great effect

on what you decide to say if only because it selects the

audience to whom you can say it. The unassisted human voice which

can reach at most a few dozen yards, imposes various conditions on a

speaker. However, with the invention of the alphabet the voice was

translated to a visual medium with the consequent loss of most of its

qualities and effects. But its range in time and space was thus given

enormous extension. At the same time that the distance from the

sender of the recipient of a message was extended, the number of

those able to decipher the message was decreased. Writing, in other

words, was a political revolution. It changed the nature of social

communication and control.

Intellectually, the visualization of the word may have made possible

the rise of dialectics and logic as they are found in Plato's dialogues.

And the Platonic quarrel with the Sophists, from this point

of view, may represent the clash of the older oral with the new

written mode of communication. For the written form of communication

permits the arrest of a mental process for private analysis and

contemplation, whereas the oral form is naturally concerned with the

public impact on an audience. The Platonic dialogue may well represent

a poise between the aesthetic claims and tendencies of these two forms

of expression, between dialectic and rhetoric.

The conflicting claims of dialectic and rhetoric or private and public

communication account for a good deal of subsequent intellectual and

social history. The Roman world divided the dispute in accordance

with the position of Seneca and of Cicero, and the mediaeval world

opposed the methods of study and teaching of the Fathers and the

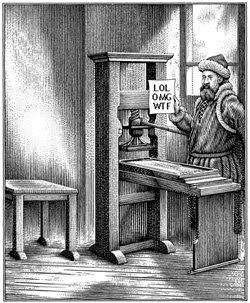

Schoolmen. But the invention of printing or letterpress upset the

mediaeval equilibrium in this matter. For the mechanization or writing

reduced the effect of the spoken word even more than had the invention

of writing. And the cheap and rapid multiplication of books not only

extended the audience for books, but it changed the methods of study

and teaching from a social to a private mode. There arose a cult of privacy.

Western culture and religion became centered in the home and the book.

Politically speaking, this social change was felt in the new intensity of

commercial exploitation of the vernaculars. Printing fostered nationalism

when the printers sought to extend their markets as widely as possible.

For any one vernacular market of newly-taught readers was larger than

the whole European community of Latin-reading and speaking scholars.

One obvious effect of writing and printing is to bind together

long tracts of time by making past writers simultaneously available.

Associated with this effect is the republicanism of letters. Anybody,

no matter what his origin or condition, has access on equal terms to the

written messages of "the mighty dead," so that we can readily link, as

most have done, the rise of democratic attitudes to the mechanization

of writing.

As the mechanization of writing advanced in speed and cheapness,

and the daily newspaper became possible, a whole series of

unpredictable social and political consequences appeared. The press

became a source of advertising revenue, for one thing. And larger

circulation called for a larger range and variety of news. This led to

the development of news-gathering agencies and techniques of great

scale. And while the newspaper took on the format of a popular daily

book, collectively written and produced, it reversed the character of

the first printed books.

At first the book had abridged time, making the reader of any

period the social equal and contemporary of Homer, Horace, or

Petrarch. However, the new book of the people, the newspaper, created

a one-day world utterly indifferent to the past, but embracing the

whole planet. The newspaper is not a time-binder but a space-binder.

Juxtaposed simultaneously in its columns are events from the next

block with events from China and Peru. And naturally the

technologically determined format of the press has had revolutionary

political consequences. It has changed everybody's way of thinking,

seeing, feeling. Perhaps the most significant single fact about the

newspaper is its date-line.

Aesthetically speaking, a week-old newspaper is of no interest at all,

even though intellectually speaking it has exactly the same components

as today's paper. Aesthetically the newspaper creates an impact of

immediacy and of super-realism. Metaphysically its mode is

existential. Its impact is that of the very process of actualization.

The entire world becomes, in this way, a laboratory in which everybody

can watch the stages of an experiment. Everybody becomes a spectator

of the biggest show on earth - namely the entire human family in its

most gossipy intimacy. One curious aspect of the press is its willingness

to be as surrealist as possible in its handling of geography and space,

while sticking rigidly to the convention of a date-line. As soon as the

same treatment is accorded time as space, we are in the world of

Joyce's ULYSSES where it is 800 B.C. and 1904 A.D. at the same time.

And it is certain from even a casual glance at modern science fiction

that the popular mind is decades ahead of the academic mind in being

already prepared to drop the date-line on newspapers, and to range as

freely in time as in space as a means of intellectual discovery.

This spectator mentality applied not only to the external world

but to history includes the habit of seeing oneself as part of the

scene, of participating in one's own audience participation, as it

were; and it receives a final degree of extension in television

where the participants in a show can easily see the broadcast

in a studio monitor while engaged in acting the show. It is noteworthy

that the spectator attitude is explicitly associated with one of the early

newspapers. For the SPECTATOR of Steele and Addison was a commentary

on the social and intellectual scene in the days before professional

news-gathering had begun. Various inventions like the telescope, the

microscope, the spectroscope, and the camera obscura coincided with

the landscape interest in painting and poetry to foster a spectator

attitude to the world. The very idea of "views" as a way of expressing

moral and political attitudes arose at this time. Popular metaphors

naturally provide an index to changing experience.

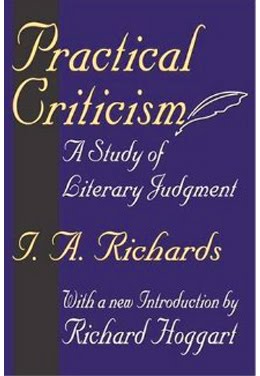

For the student of the arts and of politics it is instructive to

observe how many of the techniques developed for example, in

picturesque poetry, not only appear in the popular novel but in the

press. In fact, most current ideas of the opposition between vulgar

and sophisticated art, or between popular and esoteric culture, are

based on a considerable ignorance of the ways in which communication

takes place in society. More specifically, the general concepts of

culture have been based on an interest in the moral and intellectual

content of art forms, to the neglect of the form itself as a major

component of the expression. As attention has widened to see any

culture as a communication network, it has become apparent that there

are no non-cultural areas in any society. There is no kind of object

or activity that has not some rapport with the entire network.

The beloved detective story will serve as an example of a

supposedly non-cultural type of expression. Built around the character

of an omniscient and omni-competent sleuth whose lineage stretches

backwards from Holmes to Da Vinci it manages to be popular poetry

about the modern city. The sleuth is a master of every facet of the

city. With the skill of an organist at a five-keyboard instrument, he

can touch any note or level of metropolitan life. He is familiar with

all the dives and clubs. He knows the whole range of drinks, foods,

clothes, perfumes, as well as every intricacy of transportation routes

and schedules. Anybody in the future who wished to acquaint himself

with the full range and texture of the modern big town would not be

able to find in reputable novels anything comparable to the poetic

reportage of the detective story. The raw mechanical power that is

imparted to the ordinary metropolitan citizen by his milieu is found

in the gestures and idiom of the sleuth.

But much more remarkable, as cultural expression, is the form of

the detective story. Written backwards, in order that the effect of

the story may always be the exact reconstruction of a crime, the form

is based on the same method as that employed in laboratory experiment

and in modem historiography, archaeology, and mechanical production.

But the detective story preceded these sciences in the discovery of

this method. It is only one striking instance of popular expression

which has its tap-root in the deepest intuitions of our culture.

If the mechanization of writing had some such typical effects as

have been suggested, it is not too surprising that its extreme

development should have coincided with a tendency to switch from words

to pictures. This switch was already under way in the eighteenth

century with its spectator outlook and passion for landscape in the

arts. By the nineteenth century the demand for illustrations for

letter-press became very strong, not only in the book and newspaper

but also in the very form taken by the esoteric arts, as for instance

Rimbaud's ILLUMINATIONS. Photography and cinema may be seen as the

response to prolonged pressure of demand rather than as gratuitous

inventions. Perhaps they can be viewed as ultimate or extreme

mechanizations of writing. More probably, however, telegraphy has

claims to be considered the extreme verge of the mechanization of

writing beyond which one enters the Marconi world of the mechanization

of speech.

Like any extreme these processes reversed the original effect,

and tended to separate people from the printed word. So that in

pictorial papers and magazines even words take on the character of

landscape. Variety of types is employed to build up the page as a

visual unit rather than as a mere linear transmission of printed

words. The Chinese never had an alphabet, but their ideograms are

pictorial translations of human gestures and relationships. As our

press has become more pictorial our whole culture has become more

sympathetic to Chinese art and expression. So that the very features

of our culture which have intruded disruptively into the East have

also brought us a basis for approaching their kinds of communication.

Modern advertising is a world of ideograms.

There have been so many domestic and social revolutions

associated with the consequences of the mechanization of writing that

it is natural to wonder why so little attention has been given to the

matter. Without any special awareness of just what revolutions we have

been through we have hurried from the age of cinema into the era of

television. Between cinema and television we managed to squeeze in

radio, the mechanization of speech.

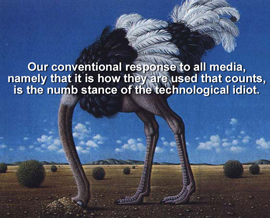

By way of obeisance to our own ingenuity, people have often felt

obliged to marvel at radio and television by exclaiming: "Although

it's happening over there, it's also happening right here." This kind

of self-hypnosis is undertaken in a spirit of uneasy propitiation of

the new god. But the real power of these deities is exerted when we

aren't looking. The mechanization of speech meant that the most

intimate whispers or the most ordinary tones of conversation could be

sent everywhere instantly from anywhere. Beside the effects of this

revolution in communication even those associated with the invention

of writing and printing are trivial events. Radio meant the widest

dispersal of the human voice and also the ultimate dispersal of

attention. For listening is not hearing any more than looking is

reading. And all the networks of human communication are becoming so

jammed that very few messages are reaching their destination. Mental

starvation in the midst of plenty is as much a feature of mass

communication as of mass production.

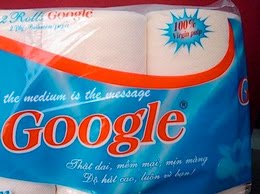

The stereotypes of advertising have been developed as the nexus

between mass consumption and mass production. Advertising has been the

means of organizing the mass market. For advertisements are

constructed scientifically as machines to stream-line and channel the

multiplicity of human desires until they are effectively geared to

production. A more effective mode of psychological collectivization

could not be imagined than that imposed by the giant stereotypes of

the desirable which are insinuated, without argument but with intimate

urgency, by the symbolist techniques of visual and auditory appeal in

advertisements. These stereotypes are not the product of chance but of

careful investigation and experiment with the human recipients. For

the present time the realities of political and social change are to

be studied in this area. Among other things, these changes mean that

events cannot be reported if they involve a degree of complexity in

excess of the available stereotypes, so that in modern diplomacy the

negotiators will naturally refuse to attempt a working agreement that

cannot be followed by or reported to non-professionals. There must be

some simple moral or national formula to hand for the diplomats to

depend upon, such as will justify them to the half-listening, half-

waking world hour by hour and day by day. In this way the new media

have compelled history and actuality to feign a simplicity that just

isn't there. Thus the magic and mythic power so characteristic of the

mass media, having first hypnotized the recipients of their messages,

have then, in effect, pronounced the real world to be an illegitimate

and reprehensible territory. The same sort of paradox is inherent in

the movie as a night-time therapy applied to the victims of dream

routines of daily work.

It would be too much in the spirit of the current effect of the

new media to brand these and allied developments as deplorable. For,

if the new reality of our time is in the main a collective dream or

nightmare brought about by the mechanization of speech (television

takes the final step of mechanizing the expressiveness of the human

figure and gesture) then we must learn the art of using all our wits

in a dream world, as did James Joyce in FINNEGANS WAKE.

On looking closely at the newspaper once more, it becomes

evident that as a popular art form it embraces the world spatially but

under the sign of a single day. The newspaper as a late stage in the

mechanization of writing is handicapped in taking the next step, which

occurs easily in radio and television, namely to cover not only many

spaces but many times, or history, simultaneously. But even the

newspaper has long felt the pressure to take this step. In juxtaposing

items from Russia, India, Iran and England, it is plain that there is

also a diversity of historical times that are being artificially and

arbitrarily elucidated under a single date line. Even in so intimate

and influential a fact as dress design, modern archaeology has

increased the range of style and idiom to include in a single season

types of attire developed many thousands of years apart. The TIME AND

WESTERN MAN of Mr. Wyndham Lewis is the classic study of the romantic

stigmata of the enthusiastic time-traveller. But the further

development of communication in space as in historical time, has

tended to lessen the romantic appeal of distant times and customs in

favour of a direct stylistic interest in their immediate value and

relevance. The modern study of the past, as of distant places, has the

effect of making them as much a part of the present as our own

problems. So that for the modern mind history has become not a

receding perspective but a present burden.

This cumulative effect of our techniques of production and of

communication has been felt everywhere in the world as an impatience

with "the dead hand of the past." As we become more familiar with the

components of this revolutionary state of mind we shall discover in

our social life as in our private life that there is no past that is

dead. And that "the dead hand of the past" is an indispensable guide

in the present.

In other words when communication devices have achieved the

speed of light, there occurs a social and historical simultaneity as

well as a local and temporal one. And since the various societies of

our world comprise many ages, as well as many places, the immediate

effect of modern communication in overlaying all of these is to create

dislocation and distress. The first impulse of reason is to cry out

for uniformity at any cost, to prevent further waste, confusion, and

madness. A clean sweep, a new start, and the abolition of historical

differences seem to be demanded for mere survival.

It would seem that even so superficial an examination of the

impact of technology on culture and politics poses some useful matters

for study. The great political discovery of the eighteenth century was

social equality. The principal insight of this century to date is

perhaps the anthropologist's awareness of cultural equality. Modern

anthropologists, deeply influenced by our new skills in communication,

have arrived at the conviction that all cultures are equal. That is to

say, that seen as communication networks, all cultures past or present

represent a uniquely valuable response to specific problems in

interpersonal and inter-social communication. This position amounts to

no more than saying that any known language possesses qualities of

expressiveness not to be found in any other language. But as a matter

of practical politics the awareness of cultural equality (a by-product

of new techniques of communication) will certainly prove as benign a

force as can be imagined, because it frees each society from the odium

of inferiority or the arrogance of superiority. Each is free to learn

from all the others while possessing itself in quiet.

And by way of abating some of the dread most people feel towards

the power of mass communications at present it might be well to

consider how with radio or the mechanization of human speech, the

hustings and the forum have given way to the round table and face-to-

face discussion in the presence of small audiences. Also, with

television has come a weakening of the magic and myth of the movie

"star." It appears that the intimacy and immediacy of the flexible television

camera and screen are much less favourable to the star system than

the movie camera and its giant screen on to which are poured such

dreams as money can buy.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL, Vol.7, Summer, 1952, pp.189-95

Toronto, June 1952.

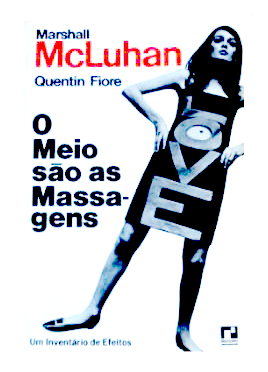

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

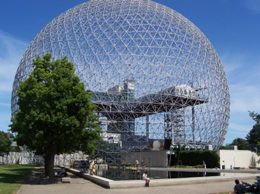

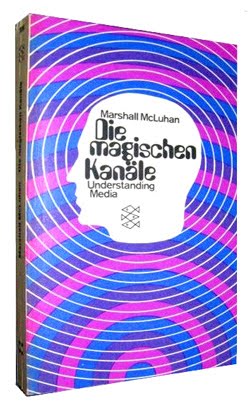

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)