McLuhan neither seeks nor deserves merely an interested reader. Rather he, as with others in the “tradition” he participates, seeks a perfect reader with a perfect case of insomnia.

sentenced to be nuzzled over a full trillion times for ever and a night till his noodle sink or swim by that ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia

(FW 120.12-14.)

------------------------------------

Marshall McLuhan and the Book:

A Reconsideration

Wayne J. Urban

In this essay, I look briefly at the work of Marshall McLuhan, particularly the Gutenberg galaxy, in which he discusses the nature of the book and the print medium through which it is produced. McLuhan’s views on the book are contextualized in terms of his other works, including his famous Understanding Media, which was published after the Gutenberg galaxy. McLuhan’s sense of himself as an avant garde intellectual and analyst of culture is evaluated, and found to be less convincing than a more nuanced view which sees him as both backward- and forward-looking in his work.

Dans cet essai, j’examine brièvement l’oeuvre du philosophe Marshall McLuhan, en particulier son the Gutenberg galaxy, ouvrage dans lequel il discute de la nature du livre et du moyen d’impression qui a servi à le produire. Les vues de McLuhan sur le livre sont mises en contexte avec celles qui se dégagent de l’ensemble de ses travaux, y compris son célèbre Understanding Media qui fut publié après the Gutenberg galaxy. Le sentiment qu’a McLuhan d’être un intellectuel d’avant-garde et un analyste de la culture est évalué. On lui préfère ici une opinion plus nuancée qui le considère comme un auteur doté d’un regard à la fois rétrograde et novateur.

The work of Marshall McLuhan constitutes a provocative episode in the intellectual history of the twentieth century. When I came upon McLuhan and his work initially, as a graduate student in the 1960s, I was attracted to his ideas for their freshness, their seeming radicalism, their audaciousness, and the combination of critique and affirmation that he offered, along with a studied splashiness in his presentation.[1] The purpose of this paper is to look again at McLuhan’s work, almost four decades later, to try and place him within the intellectual universe of the twentieth, and the twenty-first, centuries. While not the most radical, or ballyhooed of McLuhan’s views, such as his paean to television as an enormously important and revolutionary medium,[2] one of McLuhan’s most important insights was his view of the book, more specifically the book as embodied in the medium of print and as initiated with the development of the printing press and refined up to the middle of the twentieth century. McLuhan’s ideas about the phenomena of print and the book were developed most completely in his own book, published in 1962, the Gutenberg galaxy.[3] My argument in this paper is that McLuhan, as seen most clearly through his views of the book and literacy, was a major figure of the twentieth century, but one who is best seen as continuous with predecessor figures such as Max Weber, Karl Marx, or John Dewey, and successor figures such as advocates of the electronic miracles of the microcomputer and the internet. This evaluation stands in contrast to McLuhan’s own view of himself as a revolutionary thinker who caught the wave of radically novel intellectual development in the western world. In fact, like Marx and Weber, and like contemporary advocates of the new electronic media, McLuhan is both critic of that which he sought to replace, and defender of what came before that which he sought to replace. Specifically, he criticized the book and advocated the virtues of television as a replacement for the book, while he defended the oral and scribal traditions that preceded the book.

Before dealing directly with McLuhan’s work, however, a brief discussion of his life and the intellectual traditions within which he developed is in order. Born in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, in 1911, Herbert Marshall McLuhan grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where his father had moved the family in search of economic improvement, and enrolled in engineering at the University of Manitoba. He quickly discerned that he had erred in choosing that field as his subject and switched to a program in the Arts faculty that emphasized literature and philosophy. Attracted to the reading and study of ideas as they were expressed in the classics of western literature and philosophy, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree and a Gold Medal in 1933. He then took an M.A. in English at Manitoba and also earned a scholarship for further study at Cambridge University. As a colonial at Cambridge, McLuhan was forced to reprise his undergraduate studies there. His academic abilities were quickly recognized, however, and he soon earned his Cambridge B.A. He was later to receive both the M.A. and the Ph.D. (in 1943) from Cambridge. Prior to completing these degrees, however, McLuhan returned to North America to teach English at the University of Wisconsin in Madison in the USA, beginning in the autumn of 1936.[4]

After one year in Madison struggling with moderately prepared and largely poorly motivated students in multiple sections of freshman English composition, McLuhan left to take a teaching position at the University of St. Louis. Coming to the faculty of this Jesuit institution enabled McLuhan to culminate a religious journey that had taken him from the Baptist faith of his childhood to the Roman Catholic Church. Along the way, he was heavily influenced by the ideas of the English Catholic convert G. K. Chesterton, whom he read while at Cambridge.[5] Chesterton, author of mystery stories featuring the Roman Catholic priest-detective, Father Brown, and an important thinker in the development of distributism, a non-Marxist critique of raw capitalism, has appealed to more twentieth-century thinkers than McLuhan.[6] The relation between McLuhan’s Catholicism and his theories of communication was direct, if not always completely understandable. It certainly pointed to the conservative aspects of his thought, an addition or perhaps a counterpoint to what he himself seemed to think was his radicalism.

With a change in the administration of the English department at St. Louis, a change that resulted in less recognition of the talent and contributions of McLuhan by his new department chair, McLuhan moved to a new position at Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, a Catholic institution, in 1944. Almost immediately, he chafed under the constraints of small-town life and the teaching of English composition to an exceedingly complacent student body. It took McLuhan two years to find a more fulfilling position and environment at the Catholic St. Michael’s College, located within the larger, non-Catholic, University of Toronto.[7] There, having finally achieved some freedom from an onerous teaching load to develop his ideas more fully, McLuhan then turned to the task of refining and honing them.

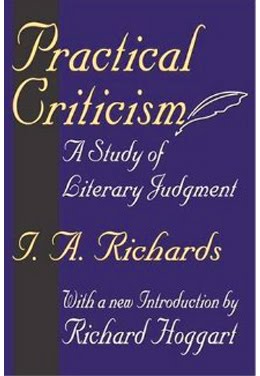

These ideas, though brought to full flower in Toronto, had roots in his studies at Cambridge as well as in his negative intellectual encounters with students and a few positive exchanges with colleagues at Wisconsin, St. Louis, and Assumption College. McLuhan learned from G.K. Chesterton and numerous others. For example, in his graduate studies in England, I.A. Richards and others developing the British version of the New Criticism in literary studies had a profound influence on McLuhan. Others whom he also read in England included Hillaire Belloc and T.S. Eliot, as well as the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain. While at St. Louis, McLuhan had a productive exchange with the noted Jesuit philosopher Walter Ong and a beneficial if somewhat bizarre encounter with the artist and writer Wyndham Lewis. Shortly after coming to Toronto, McLuhan encountered the philosopher Etienne Gilson, whose work he had long admired, as well as Harold Innis, long-time professor of political economy. Finally, in his early years at Toronto, he began a somewhat distant but real relationship with the poet Ezra Pound, whom he had studied while at Cambridge. Pound, notorious for his defence of fascism during World War II, was judged to be criminally insane and was incarcerated in a mental hospital in the District of Columbia when McLuhan first met him in June of 1948.[8] What all of these thinkers shared with McLuhan was a critical questioning of modernism and its centrifugal impact on those who subscribed to it, and a look to some aspect of the past as a counterweight to modernism.

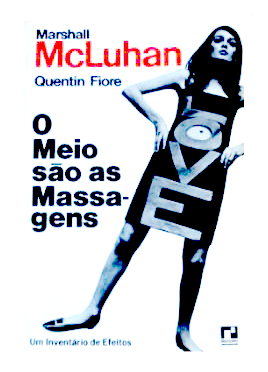

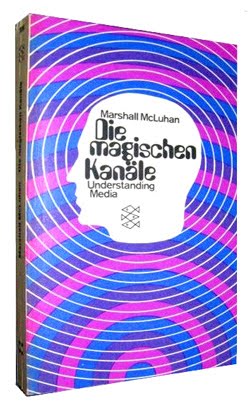

From nearly the beginning of his teaching of literature, McLuhan included popular media such as radio and film as part of his subject matter, at least partially in an effort to reach his students, many of whom seemed incapable of understanding serious literary effort. The more accessible media offered him the possibility of reaching into the lives of students unversed and uninterested in literature. This foray into popular culture, along with his sophisticated, though not necessarily profound, critique of modernism, constituted the major elements that were to characterize almost all of McLuhan’s mature works. He added to these a penchant for interdisciplinary study and a developing emphasis on the phenomena of various technologies, a word that he used as much to extend his understanding of media as for any other purpose. All these elements were included in The Mechanical Bride (1951), the Gutenberg galaxy (1962), and his most famous work, Understanding Media (1964), which was reprinted in several subsequent editions and translated into numerous foreign languages.[9]

The Mechanical Bride was published a full decade before McLuhan’s other major works and had been extant in manuscript form for at least ten years prior to its publication. Thus, it bore faint resemblance to what was to come while still revealing much of what was, and was to remain, on the mind of its author. It contained at least two characteristically McLuhan qualities. It proceeded not in any linear fashion of positing and developing an argument. Rather it was described by its author as a “mosaic,” a work that embodied multiple points of view and proceeded to rain them on the reader in a blizzard of facts, descriptions, episodes, etc., each presented as provocatively as possible without attempting to build an argument carefully or systematically. Comic strips were a major focus in the Mechanical Bride, with Al Capp’s “Li’l Abner,” “Blondie”and more specifically her long-suffering husband “Dagwood,” and “Superman” all taking centre stage. Using these characters as the points of departure, The Mechanical Bride contained a critical analysis of modern humans as in various ways detached from their roots. It also focused on the ways that advertisers controlled their audiences and exercised this control through novel presentations of off-beat ideas and themes. McLuhan was at best implicitly critical of what he was describing while at many other times he seemed to celebrate the phenomena he presented. The book also exhibited some whimsy, irony, and a penchant for the novel or even the outlandish in an attempt to reach the reader in unusual ways.[10]

McLuhan’s first book-length effort was widely, if not always positively, reviewed. He was being noticed, if not becoming as notorious as he wished, in the larger world of ideas and culture. His ideas were to get even wider circulation, and substantial refinement, with funding by the Ford Foundation in 1953 of an interdepartmental seminar in culture and communications at Toronto, and a companion journal, Explorations. Little more than a decade later, the seminar evolved into a Centre for Culture and Technology that signified, along with his subsequent books, that McLuhan was a major player in twentieth-century cultural and intellectual life in North America. The seminar and Centre involved students and faculty from several departments at Toronto, most notably psychology, anthropology, sociology, economics, and English, as well as engineering and medicine. These many disciplines also signified the breadth of the ideas being considered and developed by McLuhan and his colleagues as they studied the various means and modes of communication in contemporary society.

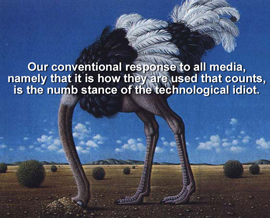

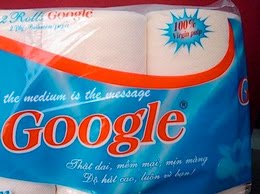

If any one of the many aphorisms coined by McLuhan in his published works can be considered to signify many, if not all, of his ideas, it would have to be “the medium is the message.” McLuhan first used this phrase in the 1950s, but it became popularized with the publication of his Understanding Media in 1964. He later summarized the meaning of this phrase as follows: “What is implied in this phrase is that the medium consists of all the services evoked or provoked by any innovation…For literate and visually oriented people it is always a shock to learn that many of the dominant attitudes of their daily lives have been structured by subliminal factors and the psychic effects of seemingly inert or neutral forms.”[11] The warp and woof, the antecedents and consequences, the multiple connotations of that aphorism were to be explored, and played with, in McLuhan’s most famous work, Understanding Media. Privately, he could be simple and relatively clear: “All that I had to say about ‘the medium is the message’…can now be put more simply, or at least more acceptably. If one says instead that each new technology creates a new human environment, it is easy to see why this new environment modifies all previous ones. It is like the ‘last ring on the tree.’@[12]

Summarizing Understanding Media is a task that is beyond the ability of this, or of most any, writer. Yet McLuhan seemed to want it that way, preferring to bombard the reader with a multitude of insights rather than attempt to convince him or her through a sustained and cogent argument. And yet, the book appears less unconventional than the Gutenberg Galaxy, since Understanding Media contained a standard apparatus of chapters not found in the earlier work. This resort to a more conventional style in Understanding Media was owing, in large part, to the constant attempts of the editors employed by the publishing house of the volume, McGraw-Hill, to push McLuhan into more standard modes of presentations. In a most unconventional procedure, however, not until page 329 is the theme of the book announced: “…not even the most lucid understanding of the peculiar force of a medium can head off the ordinary ‘closure’ of the senses that causes us to conform to the pattern of experience presented.”[13]

For McLuhan, media were more than those things that bring us news, such as radio or television. Rather, media were extensions of the bodies and minds of human beings. A medium is a technology, one that extends the human being. Examples were multiple, such as clothing extends the skin, housing extends the body’s control mechanisms, the wheel extends the foot. Most importantly for his readers, McLuhan compared and contrasted television with its immediate predecessor, radio. The visual medium was different from, and superior to, its predecessor medium in its ability to control the reactions of its viewers and influence their lives. All of these insights were geared to provoke the reader into contemplating the multiple reality and causality of life in a contemporary world of many, and often competitive if not conflicting, media.

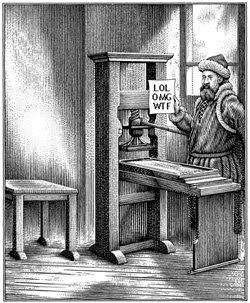

More important for the purposes of my analysis than Understanding Media, however, was the volume that McLuhan published two years before it. It is in that volume, the Gutenberg galaxy, that McLuhan turns his attention to the medium of the book, particularly as it is expressed through the technology of print. Since it was published by a university press, the press of McLuhan’s own University of Toronto, the Gutenberg galaxy was allowed to avoid most of the publishing conventions that McLuhan honoured, at least at a surface level, in Understanding Media. the Gutenberg galaxy has no chapters. Rather it is “organized” in 107 sections titled “chapter glosses” and contains an index that lists them by title in chronological order.[14] The flavour of the volume is conveyed in some of the titles of these chapter glosses: the first title is as follows: “King Lear is a working model of the process of denudation by which men translated themselves from a world of roles to a world of jobs.”[15] Literary works and their authors are frequently cited in the titles of the chapter glosses. For example, “Aretino, like Rabelais and Cervantes, proclaimed the meaning of Typography as Gargantuan, Fantastic, and Supra-human.”[16] Or: “Marlowe anticipated Whitman’s barbaric yawp by setting up a national PA system of blank verse – a rising iambic system of sound to suit the new success story.”[17] Much less cryptic and idiosyncratic, and much more directly suggestive, if not indicative, of McLuhan’s argument are the following: “With Gutenberg, Europe enters the technological phase of progress when change itself becomes the archetypal norm of social life,” and “The print-made split between head and heart is the trauma which affects Europe from Machiavelli till the present.”[18]

It is this notion of trauma that reveals McLuhan’s normative position about the medium of the printed book. For him, it represented much else besides a progressive technological device that helped free, or at least individualize, western man from an environment dominated by tradition and the Church. Responding to a question in a popular magazine interview about the profound shift in values effected by phonetic literacy, the phenomenon that was highly intensified by the invention of the printing press, McLuhan noted:

Any culture is an order of sensory preferences, and in the tribal world, the senses of touch, taste, hearing, and smell were developed for very practical reasons, to a much higher level than the strictly visual. Into this world, the phonetic alphabet fell like a bombshell, installing sight at the head of the hierarchy of senses. Literacy propelled man from the tribe, gave him an eye for an ear and replaced his integral in-depth communal interplay with visual, linear values and fragmented consciousness. As an intensification and amplification of the visual function, the phonetic alphabet diminished the role of the sense of hearing and touch and taste and smell, permeating the discontinuous culture of tribal man and translating its organic harmony and complex synaesthesia into the uniform, connected, and visual mode that we still consider the norm of “rational” existence.[19]

In a conclusion to this comment, with a typically McLuhan dash of hyperbole, he noted: “The whole man became fragmented man; the alphabet shattered the charmed circle of and resonating magic of the tribal world, exploding man into an agglomeration of specialized and psychically impoverished ‘individuals,’ or units, functioning in a world of linear time and Euclidean space.”[20]

Early in the Gutenberg galaxy, McLuhan made the point that literacy is incorrectly associated with the phenomenon of print. For McLuhan, “Only a fraction of the history of literacy has been typographic.”[21] He went on to add that, historically, the printed book had only a roughly five-hundred-year history, beginning in the fifteenth century. The book as a scribal product, however, had a history about three times as long, beginning in the fifth century BC and lasting until the printed book overtook it. Further, for McLuhan, the printed book was in a very real sense inferior to its predecessor, since print was associated with a view that “knowledge is essentially book learning.”[22] In contrast to predecessor views that saw knowledge more broadly as a way of coping with the difficulties of the world, printed books dichotomized the world into literate and illiterate sectors and institutionalized the superiority of the former over the latter by privileging the sense of sight over the other senses.

He expanded on this point of view later in the Gutenberg galaxy when he noted that “a fixed point of view becomes possible with print and ends the image as a plastic organism.” The reason for this is that “print exists by virtue of the static separation of functions and fosters a mentality that gradually resists any but a separative and compartmentalizing or specialist outlook.”[23] What print did to the sense of vision was to narrow it in a way that was not challenged until the twentieth-century invention of things such as non-representational art and experimental literature that challenged the primacy of representational image, plot, or argument.

What McLuhan was suggesting was the substantial difference in world view between the medieval and the modern human mind and, more importantly, the severe constriction of the complex, medieval world view by the print medium that created modernity. For example, early modern writers were less alienated than their successors, since they were more in touch with the multiple perspectives of their predecessors than were their successors. McLuhan illustrates this point by showing how nineteenth-century editions of Shakespeare imposed standardized punctuation on works that had been punctuated for listening, and thus could be adapted for differing audiences. Looking at Shakespeare primarily as author of works to be “read” was distinctly to limit his influence and his impact.[24]

Even more constricting was the phenomenon that the reading of printed books involved a habit and an orientation that was transferred into other realms of life. “The mere accustomation to the repetitive, lineal patterns of the printed page strongly disposed people to transfer such approaches to all kinds of problems.”[25] In other words, the mechanization characteristic of print, and the limitation of viewpoint that this mechanization effected, quickly spread to areas of modern life such as the production of goods. For McLuhan, print was the ancestor of industrialization and a causal ancestor at that.

The problem with print was that “it discourages minute verbal play, it strongly works for uniformity of spelling and uniformity of meaning,” both of which are concerns of the printer and the public created by print. In contrast, “a close attention to precise nuance of word use is an oral and not a written trait.”[26] Put bluntly, for McLuhan, “Print raises the visual features of alphabet to highest intensity of definition. Thus print carries the individuating power of the phonetic alphabet much further than manuscript culture could ever do. Print is the technology of individualism.”[27] Along with this individualism, print privileged rationalism over other ways of human communication. The phenomenon of print dichotomized the head and the heart, a dichotomy that twentieth-century intellectuals, and ordinary citizens, were struggling to overcome.[28]

McLuhan notes other paradoxical outcomes of print culture, such as the creation of both nationalism and individualism. He states: “Print created national uniformity and government centralism, but also individualism and opposition to government as such.”[29] This paradox and the tensions it unleashed were never addressed productively. Rather, they continued to work in conflict with each other and to frustrate attempts to link the individual and the nation in productive relationships.

Throughout the Gutenberg galaxy, McLuhan celebrates writers and thinkers such as Burke, Cervantes, de Tocqueville, Heidegger, Joyce, and Shakespeare for the different ways in which each of them saw through the limitations that the medium of the printed book was imposing on modern individuals and modern societies. These intellectuals are contrasted with more mainstream modernists such as Francis Bacon, Descartes, and Machiavelli, each of whom was seduced, though not necessarily in the same way, by the allure of the world of print and its simplifications.

While it is clear that criticism of print and the book pervades the pages of the Gutenberg galaxy, the superiority of post-print culture that was celebrated two years later in Understanding Media was also adumbrated, if only briefly, in the earlier work. In the context of discussing the development of print, he notes: “The print phase, however, has encountered today the new organic and biological modes of the electronic world. That is, it is now interpenetrated at its extreme development of mechanism by the electro-biological…” He then argues that the electronic media such as television facilitate a successful insight into the “native or non-literate experience, simply because we have recreated it electronically within our own culture.”[30] It is clear here, as it is elsewhere in all of his work, that McLuhan is engaged in a critique of print and books and a celebration of the newer media of the late twentieth century that, in his mind, had superseded print.

McLuhan was confronted directly with the negative connotations of his argument about print and literacy when an interviewer asked him the following question: “Isn’t the thrust of your argument, then, that the introduction of the phonetic alphabet was not progress, as has generally been assumed, but a psychic and social disaster?” His reply was characteristically ambiguous, but revealing nevertheless. “It was both. I try to avoid value judgments in these areas, but there is much evidence to suggest that man may have paid too dear a price for his new environment of specialist technology and values. Schizophrenia and alienation may be the inevitable consequences of phonetic literacy.”[31]

In that same interview McLuhan argued that the invention of the printing press intensified drastically the stresses that began with the introduction of the phonetic alphabet. He remarked that “both nationalism and industrialism…derived from the explosion of print technology in the 16th century.” The former phenomenon, nationalism, was the outcome of the printing press, which “spread…mass-produced books and printed matter across Europe, turned the vernacular regional languages of the day into uniform closed systems of national languages,…and gave birth to the entire concept of nationalism.” As for the relationship between print and the industrial revolution, he concluded:

The two go hand in hand. Printing, remember, was the first mechanization of a complex handicraft; by creating an analytic sequence of step-by-step processes, it became the blueprint of all mechanization to follow. The most important quality of print is its repeatability; it is a visual statement that can be reproduced indefinitely, and repeatability is the root of the mechanical principle that has transformed the world since Gutenberg. Typography, by producing the first uniformly repeatable commodity, also created Henry Ford, the first assembly line and the first mass production. Movable type was archetype and prototype for all subsequent industrial development…It is necessary to recognize literacy as typographic technology shaping not only production and marketing procedures but all other areas of life, from education to city planning.[32]

Thus, though McLuhan claimed that the printing press was both progressive and problematic, his final evaluation of the phenomena of literacy and the book, particularly as represented in the medium of the printing press, seems clearly to come down on the negative side. His ambivalence, and his invocation of it to mask a fundamentally negative view, put him in company with Max Weber, whose analysis in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism voiced the same reluctance to make value judgements while at length exploring the negative consequences of the phenomenon he was describing. And this same ambivalence, and an even more determined negative final judgement, characterized the analysis of capitalists and capitalism by Karl Marx. What we have in McLuhan, then, is a new explanation of modernism as an outcome of changes in communication technology, a new explanation different from both the idea-oriented analysis of Weber and the economically-oriented analysis of Marx, but an explanation that aligns with both predecessors in identifying the period of the fundamental change as the latter centuries of the second millennium, AD, as well as in emphasizing its negative consequences.[33]

The approval of the electronic medium of television in Understanding Media, just a few years after the publication of the Gutenberg galaxy, allowed McLuhan to escape his identification with Weber and Marx by positing a return to some of the virtues of pre-print culture through embracing the new medium. Such an embrace meant the possible reversal, or at least mitigation, of some of the worst excesses of individualization and abstraction that came with print.

There is much more to be said to achieve a complete description of the contours and particulars of the ideas of Marshall McLuhan. What has been presented here so far, however, is enough to let us step back from his ideas, particularly the ideas presented in the Gutenberg Galaxy, and try to locate them in the historical stream that included ideas that came before and after him.

McLuhan’s similarity to Weber and Marx places him in the company of two of the most substantial intellects of the last two centuries, both of whom, despite real differences, sought seriously to analyze and address the problems and prospects facing contemporary humankind. McLuhan’s embrace of television and his critique of print seem to be related to his aversion to becoming known as a principled anti-modernist; rather he preferred to see the latest medium he encountered, television, as a bridge back to some of what was lost in the embrace of print. Yet there was a bit of disingenuousness in this stance. McLuhan was anxious to market himself and his ideas about communication, anxious enough to make at least this student of his ideas suspicious of his normative endorsement of television.[34]

From the perspective of the formal educational world, there is another way to consider McLuhan and his work – one that sees him as far less original than he saw himself. In one of the chapter glosses to the Gutenberg galaxy, McLuhan states the following: “Peter Ramus and John Dewey were the two educational ‘surfers’ or wave-riders of antithetic periods, the Gutenberg and the Marconi or electronic.”[35] In developing this idea, as well as considering McLuhan’s desire to influence the educational world, he can be considered as simply one more in the long line of those thinkers who have tried to update Dewey and his progressive approach to pedagogy by linking him to the latest technological wrinkle to arrive on the scene. McLuhan’s embrace of television parallels Dewey’s use of the arts, crafts, and gardens in his experimental school as ways to catch pupils’ interests and to link them, through those interests, with the earlier development of humankind.[36] Of course, it should be acknowledged that Dewey did much more educationally than did McLuhan. Dewey did conduct his educational experiments in a school setting rather than ruminate about the effect of new technological developments on education and culture. What links the two is the desire to improve the present by looking to the past.

My own sense of McLuhan, however, is to see his essence in his anti-modernity, a stance that fits well with his religious orthodoxy as well as with his desire to “make a splash.” In a way he can be seen as an ancestor of both contemporary technologists who see a digital revolution happening in the world, and post-modernists who see the latest revolution as simply one more way in which older notions of truth such as those proffered by science or reason are under siege.

In regard to these contemporary movements one wonders what McLuhan might have done with the post-television creations of electronic technology such as the microcomputer and the internet. It seems quite plausible to imagine him becoming one of the loudest advocates of the electronic revolution as well as one of the many seeking to cash in on its development. The increasing anti-intellectualism of advocates of the internet who see its popularity as the “end” of books in their replacement by e-books and the demise of bookish institutions such as libraries is troubling. In the hands, or perhaps better, the fingers of students, the internet diminishes the seriousness and the comprehensiveness of the process of academic research, limiting the work involved to what can be seen on a screen and what can be accessed through key-word searches. This seems a severely truncated intellectual viewpoint, especially when compared to the processes of perusal and study of the numerous pages of books and the wealth of works contained on the shelves of libraries.[37] Though McLuhan died before these developments occurred, and the breadth of his own scholarship is clearly evident in his works, it does not seem far-fetched to see him celebrating the latest advances in electronic technology and joining with their advocates to proclaim the end of the bookish orientation that he himself had criticized so effectively in the Gutenberg galaxy. Yet it is fair also to note that McLuhan dealt with books and print substantively, rather than simply dismissing them out-of-hand as so many modern technologists seem willing to do. While these are my own elaborations of McLuhan’s ideas into a period in which he was no longer alive, they seem to be consistent with those ideas and his use of them.

While there may be other conclusions to be drawn about McLuhan and his work than those offered here, it seems fair to say that, considered from the point of view of the intellectual history of the twentieth century, he is both less unique than he thought he was and rather nicely placeable within a part of the intellectual tradition of that century. Further, when considering the latest trends in technology and learning, those that seek to become dominant in the twenty-first century, it seems clear that they are quite compatible with, though intellectually inferior to, the McLuhan intellectual world-view. Whether or not one sees the essence of McLuhan as involving technological-pedagogical innovation, or, as argued herein, a mildly principled and rather clearly consistent anti-modernism, it is obvious that there were both innovation and tradition in his work, as well as substance, and more than a bit of bombast.

NOTES

1 I would add that another quality that attracted me to McLuhan, initially, was the fact that he was a Canadian, and not another American caught up in the ideological battles between old and new left that characterized much of my graduate education.

2 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: Mc-Graw Hill, 1964).

3 Marshall McLuhan, the Gutenberg galaxy: the making of typographic man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962).

4 Biographical information is taken from W. Terence Gordon, Marshall McLuhan, Escape into Understanding: A Biography (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

5 Ibid.

6 I am thinking here especially of Garry Wills, who has spent the last four decades publishing politically astute analyses and critiques of a variety of figures in American history and American politics. Wills started out as a contributor to William Buckley’s conservative magazine, The National Review. He rather quickly left that periodical and its ideology and became more and more liberal, without abandoning, in his own mind, a genuine conservatism. For his own odyssey intellectually, as well as a discussion of how Chesterton served in his intellectual development, see Wills, Confessions of a Conservative (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1979). For a long discussion of Chesterton, see Wills, G. K. Chesterton (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961). Most recently, Wills has sought to develop his version of an anti-papal, and otherwise liberal in many ways, Catholicism. See Wills, Papal Sin: Structure of Deceit (NY: Doubleday, 2000) and Wills, Why I Am A Catholic (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002).

7 Gordon, Marshall McLuhan: Escape into Understanding.

8 Ibid., passim and 143-45.

9 Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951); the Gutenberg galaxy (1962); and Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). McLuhan published several other books after Understanding Media, but it seems fair to say that the three mentioned here are his major works and those subsequent efforts are refinements of the ideas contained in these three, particularly in Understanding Media.

10 Gordon, Marshall McLuhan, Escape into Understanding, 153-57.

11 Marshall McLuhan, “English Literature as Control Tower in Communication Study,” English Quarterly 7, 1 (1974): 4, as cited in Gordon, Marshall McLuhan, Escape into Understanding, 397.

12 Marshall McLuhan to Charles Schultz (15 Oct. 1964), McLuhan Papers, National Archives of Canada; as cited in Gordon, Marshall McLuhan, Escape into Understanding, 398.

13 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 329.

14 Marshall McLuhan, the Gutenberg galaxy, 291-94.

15 Ibid., 14.

16 Ibid., 194.

17 Ibid., 199.

18 Ibid., 155, 170.

19 “Playboy Interview,” in Eric McLuhan and Frank Zingrone, eds., Essential McLuhan (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 240-41.

20 Ibid., 241.

21 McLuhan, the Gutenberg galaxy, 75.

22 Ibid. McLuhan here is quoting G.S. Brett, Psychology Ancient and Modern (London: Longmans, 1928), 36-37.

23 McLuhan, the Gutenberg galaxy, 126.

24 Ibid., 135-36.

25 Ibid., 151.

26 Ibid., 156.

27 Ibid., 158, my emphasis.

28 Ibid., 170.

29 Ibid., 235.

30 Ibid., 46.

31 “Playboy Interview,” in Essential McLuhan, 242.

32 Ibid., 243-44.

33 Cf. Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1930; London: Routledge, 1992) and Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (New York: Modern Library, 1936).

34 For McLuhan’s first attempt, in the 1950s, to market himself and his ideas, see Gordon, Escape Into Understanding, 168-71.

35 McLuhan, the Gutenberg Galaxy, 144.

36 For example, see John Dewey, The School and Society and The Child and the Curriculum (1915; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

37 David Mash, “Libraries, Books, and Academic Freedom,” Academe 89 (May-June, 2003): 50-54.

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)