McLuhan and Recent Art History

by Frank Gillette

What follows employs a mosaic pattern of observations and probes. What follows does not, as yet, aspire to the status of hypothesis. FG.

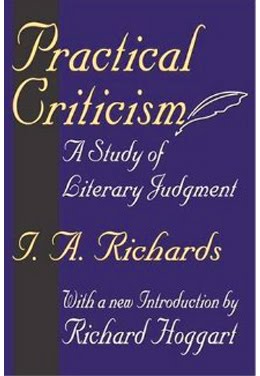

The Gutenberg Galaxy, shot through with primary references to Ruskin, Gombrich, Gilson, Panofsky and Kepes, among others, is testament enough to McLuhan's fluency with art historical ways and means.

In the meantime, the Mechanical Bride anticipates many appropriationist mix and match methods and technique. Its mix of burnt-out clichés matched with an exegesis of the early 50's oddments from advertising, book-jackets, cartoons, etc., is expressed in coy, hipster lingo, re-mixed with an astute pedagogical form. It is one frantic pedantic semantic antic. It is among the Conceptualist prototypes, a genuine Ursprache, an authentic original.

Thus, McLuhan and that sub-culture identified as the art-world are no strangers.

Freud's influence on the Surrealists, and McLuhan's influence on American art of the 60's are akin. Surrealism was informed and fructified by the looming rediscovery of the unconscious and it contents. While Pop art, Greenbergian formalism, Minimalism, and Conceptualism were in varying degrees, conscious and otherwise, wildly antipodean responses to McLuhan's take on the World. Each response being in main part a variance of "the medium is the message."

Both Freud and McLuhan, while busy frying other fish, provided ideational, even mythical, backdrops for visual culture, as well as for art praxis in their respective times. Each is essential to the descriptive lexicons typifying "art-speak" in their respective times. And both reputations have endured and survived a high variety of caricature, misattribution and debasement regarding their role and stage presence in their time.

The Surrealist mind's very activity ñ its picturesque posture and devotional irrationality ñ is, as if, a manifestation at one with the Freudian concepts of instinct, desire, and the dream. Its stupefying confidence in the liberation of desire and the exaltation of freedom is grounded in, and bracketed by, an outright catachistic embrace of psychoanalytic theories.

Likewise with McLuhanism and the mind-set of the 1960's; where notions of hot vs. cool, perceptual rations, linear vs. non-linear, and media as materia prima permeate, in distinctly opposing patterns. The discourse encircling Pop art at one end and Greenbergian formalism at the other ñ with Minimalism and Conceptualism allied as a counterforce to both.

But whereas Freud's influence was direct, McLuhan's was decidedly osmotic, passing through the art-world's semi-permeable membrane like some unacknowledged solvent. It was received within the art world's precincts as a particular strain of the overall "eschatological heave" (Mailer's coinage) which branded every aspect of 60-s culture ñ visual, political, theoretical and popular.

As to the specifics: or, five probes enumerated:

ONE:

Pop Art and Popism in general emerged with a staggering blast in the same time frame (circa. ë61-'65) that McLuhanism takes root and begins to achieve celebrity. It is the late twilight of Abstract Expressionism, the pre-eminent and dominant movement of the prior fifteen years. Televised war in Vietnam is escalating, LSD is founding a sub-culture, the Beatles have arrived. The distinctions between high and low culture is collapsing. A dazzling discontinuity prevails.

In this dicey midst, nascent contra-stances begin to spring up. Chief among them are Minimalism, that paradoxical amalgam of Neo-Platonic and empirical interests, and polymorphic Conceptualism with its diverse and multiple embodiments of disembodiment.

Like a protractor, McLuhanism's ethos opens out in a 180 degree sweep, encapsulating while corralling all of the above, knowingly or not, into a common arch description of novel terms. Within such terms, these various moves and subsequent counter-moves of the 60's are merely the inevitably results of an epic transitive clash. Their recalcitrant differences merely stubborn evidence of that clash's profound, though ironically received, complexity.

Which is to say that McLuhanism's discourse ñ with particular salience on the medium/message equation ñ provided a fresh, even unexpected, way of encompassing the fragmentary contours of the four main contesting camps, which characterized the art world in the 1960's.

TWO:

Pop Art's valorizing of the ubiquitous common image or object ñ best exemplified by Warhol's soup cans and Brillo boxes ñ dovetails with McLuhan's exploration of mass media. The mass image, prior to its appropriation by Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, et al, was initially spread through the culture in a mass medium, advertising.

Thus, both undertakings (McLuhan and the pop-artists) share a distinct ìfamily-resemblanceîÖperhaps it was the zeitgeist.

McLuhan's notion of the receding mechanical age overlapping with an onrushing electronic one is, without a bit of stretch, analogous to the receding spirit of Abstract Expressionism and Pop's disarming arrival. McLuhan's actual words are apt here: ìThe partial and specialized view-point, however noble, will not serve at all in the electric age. At the information level the same upset has occurred with the substitution of the inclusive image for the mere view-point.î Abstract Expressionism, if nothing else, was and is certainly a specialized noble viewpoint. And with Pop, aesthetic practice is certainly expanded with its omnivorous inclusion of all and every sundry mass image.

THREE:

Those dual, complimentary, hegemons, Popism and electric media ñ software and hardware in current parlance ñ flooded the collective psyche with the overwhelming force of nature itself. But success invites rebellion. And such rebellions were rife. In retrospect, Greenbergian Formalism, or color-field painting, is rather marginal among these ñ yet central to our present argument.

Cast in predicament, Greenberg's formalist aegis covers a narrow spectrum of exclusionary attitude, manifest in painting and sculpture both. Its gist is this: progress in the visual arts orbits around the core issue of material transparency. Ergo, increasing emphasis on the medium ñ that is, the physicality of pigment and the qualities of surface ñ is registered as liberation from the declared restraints of representation, inference, and pictorial illusion.

Greenberg and his coterie held Popism's world view in pitiless disdain, claiming that it had enfeebled demands made on the viewer; that it was antithetical to the putative rigors of authentic connoisseurship; that its mimicry of kitsch, advertising, cartoons et al, was nothing more than a wanton abandon of high motive.

The twisting irony here is, of course, that central and conspicuous attributes of McLuhanism can and have been implicitly drafted into the respective causa belli of these two camps.

In a sense that McLuhan would have appreciated, these rambling feud is just one of the more recent manifestations of that ageless contest between demonic and hieratic, vernacular and sacerdotal.

FOUR:

Panofsky has noted that we actually ìread what see according to the manner in which objects and events were expressed by forms under varying historical conditions.î Thus what we read when viewing a classic untitled box ñ industrially fabricate according to the precise specifications of the master Minimalist Donald Judd ñ are the historical conditions affiliated with its presentation to the world as a sculptural event. Otherwise, such a box could reasonably be taken for a very pricey, very elegant, designer-dumpster. It is the conditions of its making that assign its' status as sculpture and the pleasure derived in viewing ineluctably includes a reading of those conditions.

In Minimalism our perceptual ratios are rearranged by a vertiginous oscillation of attentive focus, swinging to and fro between the qualities of the objects' physical presence and its idealist geometric properties. From the eye's mind to the mind's eye and back, such an object's medium empirical and ephemeral at once is its message.

FIVE:

Cutting to the quick, Conceptualism is a message without a medium, at least with a medium in any traditional sense. Its measure of merit rests in the free-floating character of its propositions. Evidence of a particular Conceptualist enterprise usually commences with the diagrams, instructions, or floor plans preceding its temporary embodiment, and/or the record of its having existed at all, usually manifested in photographs, videotape or the detritus resulting from the event.

Thus the installation or the event itself drops off into the void and we are left with its before and after, with its projection and trace. Often enough, these traces are fetishized, re-entering the domain of art objects and, subsequently, the economy of the art world. But since you can only have your tongue in one cheek at a time, this maneuver for having it both ways presents a novel conundrum. Should these photographs, tapes, drawings, debris, etc., be judged by their intrinsic aesthetic value in the Ding an sich, as the thing themselves, as entities with an existence independent of the installations which cause them? Or does their merit reside exclusively in the reification of phantom events?

I suspect there are questions that McLuhan himself would have enjoyed tossing around, inasmuch and since they represent the medium/message equation with a peculiar wrinkle.

In any case, the rhizome interconnecting McLuhan's explorations with the zigzagging tactics of 60's visual artists, of all vanguard stripes, is fecund with a shared motif index, logistical repertoire, and lexical invention. And this fortuitous confluence represents a critical juncture that, in retrospect, has set the reverberating tone of our current post-modern climate. For, in Wittgenstein's signifying phrase, "To imagine a language means to imagine a form of life."

Hence, through bend of bay and swerve of shore we return to McLuhan castle and environs once again. Where we fin again, only to begin again, for these environs posses a serious strength and their river runs very deep.

Frank Gillette

NYC March, 1998

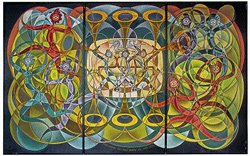

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment