Theall : "the last Victorian..."

...but if you insist on pinning me down about my own subjective reactions as I observe the reprimitivization of our culture, I would have to say that I view such upheavals with total personal dislike and dissatisfaction. I do see the prospect of a rich and creative retribalized society--free of the fragmentation and alienation of the mechanical age--emerging from this traumatic period of culture clash; but I have nothing but distaste for the process of change. As a man molded within the literate Western tradition, I do not personally cheer the dissolution of that tradition through the electric involvement of all the senses: I don't enjoy the destruction of neighborhoods by high-rises or revel in the pain of identity quest. No one could be less enthusiastic about these radical changes than myself. I am not, by temperament or conviction, a revolutionary; I would prefer a stable, changeless environment of modest services and human scale. TV and all the electric media are unraveling the entire fabric of our society, and as a man who is forced by circumstances to live within that society, I do not take delight in its disintegration.

You see, I am not a crusader; I imagine I would be most happy living in a secure preliterate environment; I would never attempt to change my world, for better or worse. Thus I derive no joy from observing the traumatic effects of media on man, although I do obtain satisfaction from grasping their modes of operation. Such comprehension is inherently cool, since it is simultaneously involvement and detachment. This posture is essential in studying media. One must begin by becoming extraenvironmental, putting oneself beyond the battle in order to study and understand the configuration of forces. It's vital to adopt a posture of arrogant superiority; instead of scurrying into a corner and wailing about what media are doing to us, one should charge straight ahead and kick them in the electrodes. They respond beautifully to such resolute treatment and soon become servants rather than masters. But without this detached involvement, I could never objectively observe media; it would be like an octopus grappling with the Empire State Building. So I employ the greatest boon of literate culture: the power of man to act without reaction--the sort of specialization by dissociation that has been the driving motive force behind Western civilization.

The Western world is being revolutionized by the electric media as rapidly as the East is being Westernized, and although the society that eventually emerges may be superior to our own, the process of change is agonizing. I must move through this pain-wracked transitional era as a scientist would move through a world of disease; once a surgeon becomes personally involved and disturbed about the condition of his patient, he loses the power to help that patient. Clinical detachment is not some kind of haughty pose I affect--nor does it reflect any lack of compassion on my part; it's simply a survival strategy. The world we are living in is not one I would have created on my own drawing board, but it's the one in which I must live, and in which the students I teach must live. If nothing else, I owe it to them to avoid the luxury of moral indignation or the troglodytic security of the ivory tower and to get down into the junk yard of environmental change and steam-shovel my way through to a comprehension of its contents and its lines of force--in order to understand how and why it is metamorphosing man.

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

4 comments:

Conservative Christian anarchist

McLuhan's slogans "The medium is the message" and "The global village" are recited like mantras in every digital atelier in the world, despite the fact that hardly anyone who quotes McLuhan reads his books. Some of them McLuhan hardly wrote in the first place, trusting assistants and collaborators to cobble them together out of recordings and notes. As his biographer Philip Marchand explains, with wry sympathy, "writing books was not McLuhan's forte."

Neither was McLuhan very influential as a scholar or teacher. From the beginning of his career, the Canadian professor with a doctorate from Cambridge stood outside the academic mainstream for which he had little patience.

The natural incompatibility of originality and academia was probably especially difficult to overcome for McLuhan, who had received his early education in North American public schools, which, then as now, offered few advantages to their most talented students. By the time he arrived at Cambridge, McLuhan had acquired what is perhaps the defining trait of autodidacts - a kernel of personal crankiness and a resistance to established authority.

In his role as social, political, and economic analyst, McLuhan was a clown. His speeches and public pronouncements helped give rise to a generation of affluent futurists and business consultants skilled at telling executives what they liked to hear, but McLuhan's own predictions and business ideas were often hilariously ill-conceived. If his urine-odor remover failed to stimulate the instincts of business executives, perhaps McLuhan could talk Tom Wolfe into collaborating on a Broadway production of a play in which the media appeared on stage as characters. This aborted script followed two other McLuhan attempts at musicals, including one in which Russian Elvis fans were given a shot at governing America.

Even in areas where McLuhan was expected to be more dependable - say, pop culture - his pronouncements were often incredible. In 1968, for instance, McLuhan attempted to explain to readers of Playboy why the miniskirt was not sexy.

With McLuhan, the accuracy of his commentary was beside the point. "What is truth?" asked McLuhan in 1974, and he answered with a quote he attributed to Agatha Christie's iconoclastic investigator Hercule Poirot: "Eet ees whatever upsets zee applecart."

"You have not studied Joyce or Baudelaire yet, or you would have no problems in understanding my procedure," McLuhan wrote to one detractor with whom he was especially irritated. "I have no theories whatever about anything. I make observations by way of discovering contours, lines of force, and pressures. I satirize at all times, and my hyperboles are as nothing compared to the events to which they refer."

McLuhan's strange scholarship and unprofitable business advice set him apart from such popular lecturers as Alvin Toffler, Peter Drucker, and even John Naisbitt, with whom he collaborated. McLuhan was stunningly oblivious to the question of how business executives would implement his suggestions and what results would be achieved. His presentations wandered far from their announced topics, and his audiences often ended up as baffled as his readers.

Also, McLuhan was never a cheerleader for the technological elite. "There are many people for whom 'thinking' necessarily means identifying with existing trends," he wrote in a 1974 missive to the The Toronto Star. In this letter, McLuhan warned that electronic civilization was creating conditions in which human life would be treated as an expendable fungus, and he passionately protested against it.

In his personal habits, McLuhan was entirely literary.

He read ceaselessly. He was not in favor of television but enjoyed the cleverness of it. At the movies, he often fell asleep. McLuhan was a political conservative and a convert to Catholicism, and his pronouncements on current events always had an element of loony dispassion and professorial absent-mindedness.

At heart, McLuhan was not a futurist at all but a critic and an academic rebel in the tradition of Henry Adams, another conservative Christian mystic who preferred analyzing large-scale trends to compiling sober catalogs of unenlightening facts.

On the other hand, McLuhan was not a Luddite. "Value judgments create smog in our culture and distract attention from processes," he wrote to another detractor. In place of moralistic hand-wringing, McLuhan urged his listeners to take a stance of awareness and responsibility. "There is a deep-seated repugnance in the human breast against understanding the processes in which we are involved," he complained. "Such understanding involves far too much responsibility for our actions."

Faith in Christ

Marshall McLuhan was a skeptic, a joker, and an erudite maniac. He read too deeply from Finnegans Wake, had too great a fondness for puns, and never allowed his fun to be ruined by the adoption of a coherent point of view. He was dismayed by any attempt to pin him down to a consistent analysis and dismissive of criticism that his plans were impractical or absurd. His characteristic comment during one academic debate has taken on a mythic life of its own. In response to a renowned American sociologist, McLuhan countered: "You don't like those ideas? I got others."

In a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, with whom he had a long friendship, McLuhan argued that in the modern electronic environment, it is inadvisable to be coherent. "Any moment of arrest or stasis permits the public to shoot you down." McLuhan preferred to make his rebuttals in the form of a quip. As he explained to Trudeau: "I have yet to find a situation in which there is not great help in the phrase: 'You think my fallacy is all wrong?' It is literally disarming, pulling the ground out from under every situation! It can be said with a certain amount of poignancy and mock deliberation."

McLuhan's idea that media are extensions of man was influenced by the work of the Catholic philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who believed that the use of electricity extends the central nervous system. McLuhan's mysticism sometimes led him to hope, as had Teilhard, that electronic civilization would prove a spiritual leap forward and put humankind in closer contact with God.

But McLuhan did not hold on to this brief hope, and he later decided that the electronic unification of humanity was only a facsimile of the mystical body. As an unholy imposter, the electronic universe was "a blatant manifestation of the Anti-Christ." Satan, McLuhan remarked, "is a very great electric engineer."

Though he enjoyed observing the battles of the day as they were played out in the media, McLuhan was deeply attached to the church and suspicious enough of worldly goings-on to be immune to large-scale politics or reformation movements. He put his faith in Christ. When challenged by a British journalist about the deleterious effects of electronic culture, McLuhan responded that he had "no doubt at all that Christus vincit. That is why a Christian cannot but be amused at the antics of worldlings to 'put us on.'" The true Christian strategy, McLuhan believed, was "pragmatic and tentative."

Pragmatic and tentative hardly seem the right adjectives for one of our era's greatest provocateurs. But in light of his Catholicism, McLuhan's pragmatism makes sense. Mystics are attuned to the voice of the Holy Spirit coming in directly, and they are the great demolishers of doctrine. Pragmatic does not mean practical, but nonsystematic. Tentative does not mean weak, but provisional and willing to change course under the influence of new revelations.

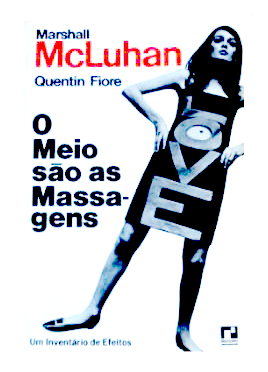

The medium is a message ... from Satan

When McLuhan said that the medium is the message, he was trying to raise an alarm. Big debates over the content of media - such as the controversies over sex and violence on television - miss the point entirely, he argued, because the transformation of human life is carried on by the form of the medium rather than any specific program transmitted by it. Protesting the programs carried by the media is futile because the owners of the media are always happy to give the public exactly what it wants. Standing in opposition to any sort of programming is not only a lonely and isolating posture, it also serves to advance the popularity of the programming protested.

Of course the content of a medium is important, but according to McLuhan the content is not the programming. (This sort of content, McLuhan wrote, "is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.") The real content of any medium is the user of the medium. We are the content of our media. Each medium delivers a new form of human being, whose qualities are suited to it.

"All media exist to invest our lives with artificial perception and arbitrary values," wrote McLuhan, pointing out that electronic culture is no more corrupt in this sense than is print culture, or the preliterate culture of poetry, song, and myth. Language is a type of technology, too, McLuhan noted, anticipating and rejecting the moralism of modern-day Luddites.

From Samuel Butler's Erewhon, McLuhan got the idea that human beings are the sexual organs of the technological world. The user of any medium is its content, just as the content of genetic code is the individual member of the species that manifests and transmits it. When he used his most oracular tone, McLuhan's description of man's servitude to media was chilling.

"Electromagnetic technology requires utter human docility and quiescence of meditation such as befits an organism that now wears its brain outside its skull and its nerves outside its hide. Man must serve his electronic technology with the same servo-mechanistic fidelity with which he served his coracle, his canoe, his typography, and all other extensions of his physical organs. But there is this difference, that previous technologies were partial and fragmentary, and the electric is total and inclusive.... No further acceleration is possible this side of the light barrier."

McLuhan believed that the message of electronic media brought dangerous news for humanity: it brought news of the end of humanity as it has known itself in the 3,000 years since the invention of the phonetic alphabet. The literate-mechanical interlude between two great organic periods of culture is coming to an end as we watch and as we listen.

Moralistic resistance is futile, according to McLuhan, and serves only to make things worse. "On a moving highway, the vehicle that backs up is accelerating in relation to the highway situation," he wrote. "Such would be the ironical status of the cultural reactionary. When the trend is one way, his resistance insures a greater speed of change."

And yet McLuhan's answer to the neo-Luddites presumed that in fact there is something faster than the speed of electronic media: thinking. McLuhan urged us to think ahead. "Control over change would seem to consist in moving not with it but ahead of it. Anticipation gives the power to deflect and control force." By giving up our resistance and allowing our minds to travel ahead of the coming changes, McLuhan allowed some chance that we will rescue something of our humanity or invent something better to replace it.

Conflicting assumptions have been proffered about Marshall McLuhan's Roman Catholic beliefs: (a) that he was a “compartmentalized Catholic” who kept his Sunday beliefs separate from his Monday-to-Saturday academic thinking; (b) that his Catholicism was ubiquitous, and thus the “global village” is a longing for one world body as camouflaged Teilhard de Chardin; (c) that McLuhan was an academic who addressed all topics, including religious ones, orally and in writing but not with a proselytizing perspective; (d) that as a convert to Catholicism (in the spirit of Chesterton and Lewis) he was a clever and subtle evangelical who infused academe with adapted theology; and (e) that some mixture of these assumptions is likely to be true, although McLuhan kept his articles of faith largely off the record.

The Medium Is the Mass: Marshall McLuhan's Catholicism and catholicism

by Thomas W. Cooper

Post a Comment