The Sensus Communis

Aristotle describes the sense power as a logos, which is generally translated as "proportion". oud h aisJhsiV megeJoV estin, alla logoV tiV kai dunamiV ekeinou.(De Anima II, xii 424a 25) We may note briefly that Thomas Aquinas uses the term "ratio" to translate "logos". Of course, "logos" is itself an extremely analogical term, and the latin "ratio" shares much of the family of meaning. In what follows, Aristotle compares the logos of the senses to the adjustment and pitch of a lyre. If the strings of a lyre are struck too hard, its tuning is destroyed. Likewise, if a sense organ is over-excited, its proportion or tuning is destroyed, and this tuning or proportion is one and the same as the sense itself.

Marshall McLuhan develops this line, and we may say that it is central to his thought. Various media excite certain senses, both to the detriment of the whole of the other senses, and sense cognition as a whole. This thought is found throughout McLuhan's works. For example:

Song itself is a slowing down of speech so that the songs of each culture are uniquely patterned by their speech. This is equally true of dance, since every culture that is or ever was in the world possesses a unique ratio of sensory life that can be detected at once in its speech, its dances, or its songs. Any technological innovation in any culture whatever at once changes all these sensory ratios, making all the older songs and dances seem very odd and dated to the young. In all cases sensory change is levered by new technical innovations, since new technology inevitably creates new environments that act incessantly on the sensorium.

(War and Peace in the Global Village, p. 136.)

The effects of new technologies upon the senses may pose a threat to man. McLuhan writes:

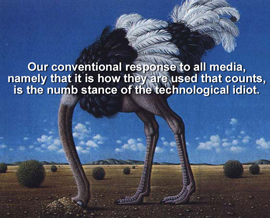

The principle of numbness comes into play with electric technology, as with any other. We have to numb our central nervous system when it is extended and exposed, or we will die. Thus the age of anxiety and of electric media ias also the age of the unconscious and of apathy.

(Understanding Media, ch. 4 "The Gadget Lover")

If numbness is a mechanism for coping with sensory overload or imbalance, we might observe with Aristotle that the ultimate and terminal point is the death of organism. Every animal possesses the sense of touch, indeed the sense of touch defines the animal. The sense of touch is a kind of mean (mesothV) between all tangible qualities, and the basis of all the other senses. If deprived of the sense of touch, animals must die. To cease to feel is to cease to be an animal. (cf De Anima III, xiii, 435a-b)

The sensus communis is 'the sense of senses'. It is not quite the same as intellect, but it is still a step above simple sensation. Aristotle presents his doctrine of the common sense in the first chapter of Book III of De Anima. Each sense has its own proper object or objects, as touch perceives hardness, softness, heat, cold and so forth, and hearing perceives tone. Vision perceives color. However, these sense data by themselves do not constitute the perception of things as such. There are attributes called the common sensibles which involve all the senses working together. These are motion, rest, shape, size, number and unity. There is thus a sense that oversees and unifies the other senses, whether this be conceived as a separate faculty or a harmonic synergy of all the proper senses.

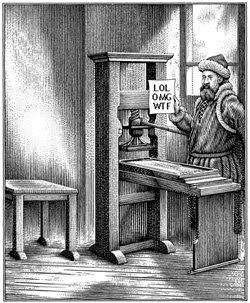

McLuhan's insight was that this common sense is trained. It can and does acquire habits. It requires very specific habits when sense experience is mediated by various technologies (even a technology as simple as writing). In fact, the function of the common sense in unifying sense data in due proportion in order to present the solid and moving world is extended, and partially supplanted by electronic media. The result of these technologies is that the new man is already "an organism that now wears its brain outside its skull and its nerves outside its hide."(Understanding Media, ch. 6 "Media as Translators"). Previous technologies also extended our senses, but the electronic media are all inclusive. For the new man to be deprived on his Internet, telephone, television and so forth is as traumatic as losing one of his organic senses. Not only does the technology serve the man, but the man also serves the technology.

If the electronic technology places the center of our common sense outside ourselves, it also creates a common sense which is shared by a community. McLuhan writes that

"an external consensus or conscience is now as necessary as private consciousness".(Understanding Media, ch. 6 "Media as Translators")

While the media creates its own external consensus, and so programs man, man also programs the media. I may comment that this can create a feedback loop. For example, the television news creates a world for us. For myself and my neighbours, the Persian Gulf War or the Kosovo conflict are synonymous with the television experience. The Persian Gulf War is as much a landmark marked in television as Melrose Place. It is easy to see how the News feeds upon itself. The fact of the electronic mediation of the event in turn becomes electronically mediated. When he who programs his media environment is himself the product of that environment, he creates an environment that is no longer merely a transparent medium of communication, but a reality in itself.

McLuhan refers specifically to the classical doctrine of the common sense:

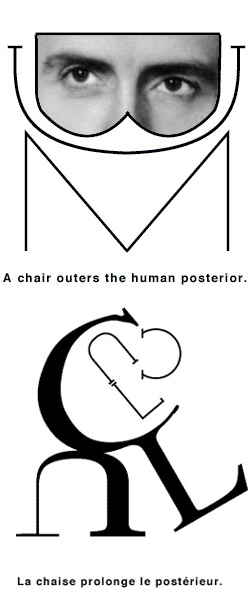

Our very word "grasp" or "apprehension" points to the process of getting at one thing through another, of handling and sensing many facets at a time through more than one sense at a time. It begins to be evident that "touch" is not skin but the interplay of the senses, and "keeping in touch" or "getting in touch" is a matter of a fruitful meeting of the senses, of sight translated into sound and sound into movement, and taste and smell. The "common sense" was for many centuries held to be the peculiar human power of translating one kind of experience of one sense into all the senses, and presenting the result continuously as a unified image to the mind. In fact, the image of a unified ratio among the senses was long held to be the mark of our rationality, and may in the computer age easily become so again.

(Understanding Media, ch. 6 "Media as Translators")

“It may very well be that in our conscious inner lives, the interplay among our senses is what constitutes the sense of touch. Perhaps touch is not just skin contact with things, but the very life of things in the mind.”

“It begins to be evident that ‘touch’ is not skin but the interplay of the senses, and ‘keeping in touch’ or ‘getting in touch’ is a matter of a fruitful meeting of the senses, of sight translated into sound and sound into movement, and taste and smell. The ‘common sense’ was for many centuries held to be the peculiar human power of translating one kind of experience of one sense into all the senses, and presenting the result continuously as a unified image to the mind. In fact, this image of a unified ratio among the senses was long held to be the mark of our rationality, and may in the computer age easily become so again.”

“Fragmentation by means of visual stress occurs in that isolation of moment in time, or aspect in space, that is beyond the power of touch, or hearing, or smell, or movement. By imposing unvisualizable relationships that are the result of instant speed, electric technology dethrones the visual sense and restores us to the dominion of synesthesia, and the close interinvolvement of the other senses.”

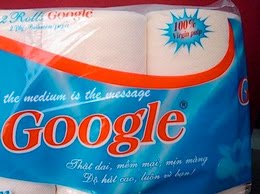

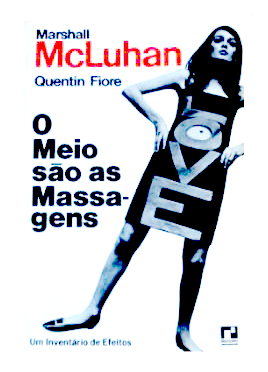

The Medium is the Massage

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)