Edmund [Ted] Carpenter :

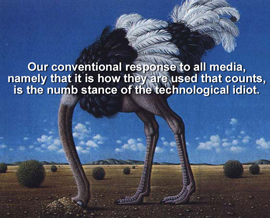

"Surrealists are able to seize on certain basic ideas I think and they were interested in the coexistence of contraries. Essentially I think what they did was to extend our notion of what is natural...

The surrealists collected ethnographic art, but they didn’t bundle it by cultural area. They were not interested in history, in culture, in chronology, in function. They were interested in juxtaposing these things to see if there were any patterns that connected. The anthropologists say an object takes its value from the culture that produced it, that it has no value outside of that. Well the surrealists go beyond that. They say that it may contain within itself elements that will declare itself."

From : Donald Theall, Thursday, 31 January 2002.

Peter is quite right when he stresses the importance of Carpenter's role as the person who initially interested McLuhan in many of his borrowings from anthropology. If you look at McLuhan's work prior to 1950 or thereabouts and compare it with his work by 1953 or thereabouts, you will notice his growing interest in anthropological questions. It is worth noting that he first met Carpenter at a meeting with Innis in 1948, but he actually became deeply involved with Carpenter in 1951. I can personally attest to this, since I was taking an anthropology course with Carpenter in 1950-1 and taking a course with McLuhan and working under him on my Master's thesis in the same period. I believe the first personal social encounter they had was when we invited both of them and their wives for an evening to our apartment. Marshall and Ted really clicked and they became colleagues and friends who talked frequently. In the winter of 1952-3. I acted as a secretary to their discussions of the application to the Ford Foundation and assisted in doing preliminary drafts for them. The other contributor at this time was Marshall's lifelong friend, the political economist, Tom Easterbrook, who had a lot to do with McLuhan's initially becoming interested in Innis. But Carpenter was the prime influence opening up Marshall's interest in the newer interest in anthropology Sapir, Boas, the culture and personality school, Whorf, the Smiths, Hall, etc., supplementing the knowledge of anthropology that Marshall had developed from his literary studies and Joyce Levi Bruhl, Malinowski, Marcel Jousse and other such figures. Carpenter also encouraged Mcluhan's reading into major figures in the history of anthropology such as Edward Taylor.

Another vital area was Carpenter's own field work, especially in the North, which plays an important role in early investigation of modes of space and time, questions of language and communication and the like. And when Explorations started in 1953 (Carpenter's idea actually), Carpenter brought in the anthropological and social scientific side like Dorothy Lee.

Essentially it was a cross-fertilization, since they sparked off one anther's interests so it was possible to see Carpenter coming to speak of _Ulysses_ as a mode of anthropology. Since they became such close friends, the relationship is complex and to fully discuss it would take a lot more space. For those interested I think that Bob Dobb's suggestion of Carpenter's appendix in _The Virtual Marshall McLuhan_ is helpful in this respect. And perhaps some of the discussion in passing of Carpenter and McLuhan compliment it, although unfortunately I did not go as deeply into the anthropology connection as I would have liked. It is, as Peter suggested, most important.

Donald Theall

----------------------------------

We apologize for putting the Appendix here at the beginning but we were afraid that our dog might eat it again ... so here it is ... [FYI : its OK if your dog wants to eat it !] ... ANYWAYS, on to the Appendix ! :

APPENDIX

MENIPPEAN TOPICS

The chief techniques of defining a work as Menippean satire have been three: either (a) simply by the formula, "a mixture of verse and prose," or (b) by a comparison of its contents with those of a known Menippean satire, or (c) by means of a "definitive" list of features. Each of these is inadequate to deal with the problem of definition of the form, Menippean satire. The first is inadequate both because it allows for the inclusion of works that are not Menippean, and because it excludes a great variety of works that are - that are either wholly in verse or wholly in prose. The second is inadequate because it too makes no provision for innovation. While the third (and most popular) likewise does not provide for innovation, it is also inadequate because critics have not agreed upon what such a list should contain and because, as this appendix illustrates, a complete and thereby definitive list would be unwieldy if it were in fact possible to compile one. Further, in all probability, no Menippean satire would use all of the ingredients of such a list. Moreover, all three techniques are inadequate because they result from appraising Menippean satire abstractly and descriptively, from a distance, and because they ignore the interaction of the satire with the reader.

As has been shown in Part One, descriptive or abstract approaches fail to come to grips with Menippean satire for the reason that it is inseparable from its effect on its audience. All of the features hitherto used to describe the form, or any example of it, may be regarded as tactics chosen by a Menippist to engage and retune the sensibilities of a reader by deliberately violating his sense of decorum in one or another way. If the catalog of features appears to grow with each period of Menippism, then, it does so because the Menippist has a new, or at least a different, audience sensibility to contend with. For each change of sensibility implies both an intensifying of awareness in some areas of experience and a blunting of awareness in others. Furthermore, the catalog may be enlarged for the Menippist by the development, either through his own work or others', of new literary patterns and techniques. This may in some measure account for the paradoxical fact that Menippean satire is at once highly experimental and highly conservative of tradition (it is mimetic).

The following list of Menippean topics does not attempt to be exhaustive: it includes little more than the commonplace features - e.g., those discussed by Frye, Williams, Bakhtin and Korkowski. While its size may demonstrate the futility of a merely descriptive approach, the list may serve another purpose. A structural study of these and other Menippean topics may eventually yield basic patterns of Menippean decorum which will in turn provide greater knowledge of how human perception is altered and managed.

TOPICS:

Almanackers. They were often used as the butts of the satires, as street-level philosophi gloriosi. Cf. The Owle's Almanacke by L.L. (Laurence Lyly). Astrologers have been attacked regularly by Menippists since Lucian's Astrologia. Cf. Nashe ("Adam Fouleweather"), Rabelais, Dekker.

Anonymous Author. The author's anonymity is apologised for in a fake introduction, for example, one written by the printer or bookseller who might plead any of several reasons. A common reason is that the author, a man of quality, does not wish to reveal himself as a writer of this sort of production. E.g.: Donne's Ignatius, His Conclave, Swift's Tale. In a variant, Joyce would often aver that his interlocutors in conversation, or passersby in the street, were composing and writing Finnegans Wake, not he.

Apologiae for the Work. One or more apologies are often used to establish relations to other Menippists, by citation, by reference, or by plagiarism. They can be used to establish tone, to banter with the reader, or to lay trails of red herrings. They may appear at the beginning of the work (as in Donne's Ignatius or in French editions of La Satyre Menippée) or anywhere inside as a digression (as in Harington's Ajax and Sterne's Tristram Shandy).

Autonomous Author. The author exults in a freedom to do whatever occurs to him. This topic is frequent. Examples include Lucian, Seneca, Fronto, Synesius, Erasmus (Folly), the Obscure Epistolers, Agrippa, Despérieres' dogs, Rabelais, Swift, Sterne, Byron. Sterne: "I have a strong propensity in me to begin this chapter very nonsensically, and I will not balk my fancy. - Accordingly I set off thus." (Tristram, p.74).

Autonomous Pen. The pen, or the act of writing, is remarked to take control of the author or narrative and to pursue its own course, observed and commented upon by the author who feigns powerlessness to control it. Ancient mock-eulogists had similarly feigned powerlessness to control their rambling oratory. E.g.: Epistolae Obscurorum Virorum (1516); Swift, Tale of a Tub; Sterne, Tristram; Nashe, Lenten Stuffe. Sterne has: "In a word, my pen takes its course... I write a careless kind of civil, nonsensical, good humoured Shandean book, which will do all your hearts good...." And: "But this is neither here nor there - why do I mention it? - ask my pen - it governs me – I govern not it." Tristram Shandy, ed., Work, pp.436, 416)Banquet. A favored Menippean device for displaying gluttony and other excesses, this topic also serves as both a strategy and a symbol of Menippean encyclopedism. The range of users is from Petronius (Trimalchio) through Rabelais to Finnegans Wake. (In the ballad, the party at the Wake becomes so rowdy that the corpse rises and joins in the fun.) The Wake is a banquet in many senses: of history, of learning, of languages, of personae, of words and puns, etc. Other examples may be found in Lucian, Convivium, the symposia of Varro, Athenaeus' Deipno-sophists, Macrobius, Beroalde's (Francois Beroalde de Verville's) Moyen de Parvenir (a philosophic banquet of the dead), La Satyre Menippée and Bouchet's Les Serées (1583-4). In the sixteenth century, the French seem to have enjoyed Menippean banquets particularly. Perhaps this topic is a direct link to the derivation of "satire" from satura lanx. See also Michael Coffey's article in the Oxford Classical Dictionary for a brief conspectus of ancient symposium literature.Blustering Narrator. The author asserts his authority (extreme), an assertion often couched in Herculean terms. This is often accompanied by a teasing of the reader and chitchat or feigned worry about the book's organization. Swift's is perhaps the most complete example. The hack, in Tale of a Tub, claims "Absolute Authority in Right, as the freshest Modern, which gives me a Despotic Power over all Authors before me..." and so on. This remark is contained in a "Panegyrical Preface," which is put in Section V of the Tale. The long line of Menippean precedents includes Lucian's Alexander the False Prophet, Cornelius Agrippa's De Incertitudine, Nashe's Lenten Stuffe, Burton's Anatomy (e.g., II.4.2.1, III.2.3, and I.2.4.7), and John Taylor. In A Voyage Round the World, Dunton demands, as he opens a new chapter, "Room for a Rambler - (or else I'll run over ye)."

Bookseller. The bookseller is used as an alternative persona by the (sometimes anonymous) author. In this guise, remarks can be made that bridge lacunas (q.v.) in the text, to provide prefaces or editorial marginalia or footnotes, or all of these. Swift's Tale is a representative example; others include John Taylor and Dunton ("Nimshag's" treatise on gingerbread). The anonymously-provided Catalog appended to C.G. Finney's The Circus of Dr. Lao is a more recent example.

Catalogs and Inventories. This digressive device shatters narrative and disrupts any attempt to establish single point of view or logical sequence. The arch-practitioners are Rabelais and Joyce. In the more learned writers, it is used as a device for moving the basis of the discussion from efficient to formal cause of an event or situation. It can also become a linguistic activity of the text itself, as with Joyce's thunders. Korkowski (p.242) cites Rabelais as the inventor of this topic and attributes its invention to the "new directions" in reading made possible by printing. This topic would seem to be another descendant of satura lanx, and to be writ large in other topics such as the banquet and encyclopedism. In its relation to the latter, it is often used to lampoon the cullings, anthologies and sham learning (reduced and systematized for efficiency) promoted by the gloriosi. The catalog technique is essentially grammatical. Catalogs can (and do) include anything - the contents of pockets, grocery lists, pawnshop receipts, ships' names, book titles (real or fake or both).

Descent into the Underworld or Afterlife. This topic is related to those of the tour through hell (or heaven), the fantastic journey, travel to the moon, Dialogs of the Dead and imaginary conversations (Cf. Landor). A fundamental Menippean strategy directly related to Cynicism, the descent is useful for exposing folly and pretension in this life by way of the "democratic" levelling and occasional comeuppances of the next. Swift's tour of the madhouse is a variety of the tour through hell: several of his "madmen" are doing, by their own inclination, exactly what the damned in other Menippean satires - particularly Dunton's Second Part of the New Quevedo - were doing as a punishment in the next world. This topic is especially used against the philosophi gloriosi, intellectual and social cranks, and snobs of all kinds. Menippus probably wrote one: certainly his two greatest ancient imitators did so - Varro and Lucian. Seneca's Claudius is of this type.

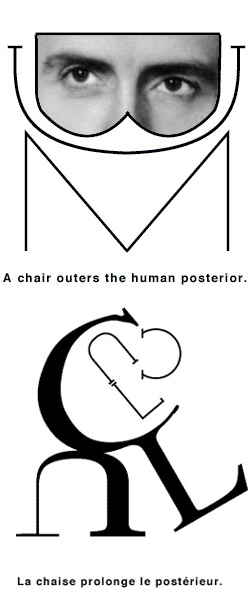

Diagrams and Drawings. The author reproduces in the text engineering plans for assembly of real or imagined machines, that may or may not be referred to in the text of the satire, and that may or may not work when assembled according to instructions (which may or may not be provided). This topic is often used to lampoon physicists, engineers and other "projectors" and schemers. In Harington's Ajax, to cite one example, none of the parts in the "disassembled" drawing can be found in the "assembled" drawing.

Dialogs of the Dead. A variant of the topics of Banquet and Descent into the Underworld, this device allows a cast of characters widely separated in time to be brought together. Their conversation, sometimes with the narrator, may run to matters concerning the audience for the satire, or each other, or trifles, or all of these.

Digressiveness. This has been called the heart and soul of Menippean satire. It is achieved in many ways. Nearly every Menippean topic is a form of digression from the normal or expected, ranging from violations of stylistic decorum to violations of narrative sequence, of time (Dialogs of the Dead), of probability (the author writes before birth or after death), of physical size or capacity (Rabelais), and so on. This can also take the form of repeatedly promising to come to the point, and never doing it, as in Harington, Dunton, Swift and Sterne, for example. The point of a passage in Finnegans Wake is seldom found except after extreme labors with the text, and then it may be an irrelevancy. For the Menippist, the labors are the point. In a variant, John Fowles provided several alternative endings to The French Lieutenant's Woman. Inherent in the structure of the frame tale (Milesian tale) and the double-plot epyllion, digressiveness is a strategy for attacking and adjusting the reader's sensibilities. It is a form of structural ambiguity.

Diogenes. He and other Cynic philosophers may be used in a satire as key characters, or may just be referred to now and then, or they can be used to provide running commentary from the sidelines on a satire. Rabelais gives his reader "licence" concerning his "pantagrueline Sentences" (a satire on Peter Lombard et al.) "to call them Diogenical." He parodies and greatly expands the account in Lucian's How to Write History of Diogenes' tub (Prologue to the Tiers Livre). The Tub, far more to Menippists than just clothing, reappears in Swift's Tale. A "tale of a tub" was, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an epithet for a kind of writing "suited to flimflam, idle discourse and a tale (sic) of a roasted horse" (A.C. Guthkelch and D.N. Smith, eds. of A Tale of a Tub). Equally, doggishness is invoked, as by Dunton:

"There stood Diogenes the Cynic, snarling at two Devils, that were going to Muzzle him, for he was so abominable Currish, he bit the Devils that came near him, His chief Clamour was... the Devils to quiet him, had promis'd to release him in Fifty years." (Second Part of the New Quevedo, p.78).Menippus also appears frequently in Menippean literature, e.g., in Lucian, or in Butler's "Hudibras in Prose," Mercuriis Menippeus. Burton's use of Democritus is proverbial. This topic is related to the establishment of the pedigree of a satire, as to Dialogs of the Dead and Digressiveness of time. It allows the Cynic spirit to be injected directly into the work.

Do it Yourself. The reader is told to add to, subtract from or rearrange the materials of the text to suit himself. In a muted form, the reader is advised to skip certain chapters or sections of the work as worthless or as potentially offensive (as Sterne, to his sensitive female reader). In another variation, the reader is told to refer immediately to other places in the text, which may be real or imaginary, apposite or not. An aspect of digressiveness, this device breaks narrative and continuity and helps to attract attention to the act of reading and to the text as an artefact. Thus it is related to the topics, lacuna-making and lacuna-pretending. Swift: "The necessity of the Digression will easily excuse the length; and I have chosen for it as proper a Place as I could readily find. If the judicious Reader can assign a fitter, I do here empower him to remove it into any other Corner he pleases. And I so return with great Alacrity to pursue a more important Concern." Sterne opens Vol. V, Chapter X by inviting the reader to fill in his own reasons for the pause in Trim's oration.

Doggishness. This topic includes dog-conversation, dog-philosophy, and other references to dogs. Directly related to the Greek pun on dog and Cynic, this topic serves to establish Menippean pedigree and to introduce the Cynic attitude and tone into a satire. Cf., Lucian, Rabelais, Byron, and others. "The fourth dialogue in the Cymbalum Mundi of Despérieres is a conversation between two dogs, Hylactor, or 'Barker,' and Pamphagus, or 'Devour-all,' who are well-versed in the anti-conventional sentiments of early Greek Cynicism; they look upon the human race with snarling disdain." (Korkowski, p.231)

Euphuism. Though not necessarily a Menippean topic, Euphuism yet has the potential to be one and exhibits a number of Menippean features including the display of learning, the use of incidental verses, and (sometimes) the dialog form. Euphuism was practised chiefly by John Lyly, William Painter, Thomas Lodge, Robert Greene and Nicholas Breton. Greene moved on to Menippism, with his Planetomachia and a series of "deathbed" productions. Whereas Menippean epistolary writings tend to come from the next world, Euphuistic "letters" are exchanged between romantic heroes and heroines, their friends, rivals, parents, and enemies. There is little mock or ridicule of learning in Euphuism.

Excess Baggage. Under this topic may be grouped all manner of illusions, pretensions, false learning or assumptions, etc., that are to be shed. This topic is a typically Cynic aspect of Menippism. Antisthenes, a student of Socrates and the man generally regarded as the first Cynic (in belief if not in outlandish behavior) replied, on being asked what learning was most necessary, "how to get rid of having anything to unlearn." Lucian's Charon observes, "... Hermes, you see what they [normal people] do and how ambitious they are, vying with each other for offices, honours, and possessions, all of which they must leave behind them and come down to us with but a single obol... Nothing that is in honour here is eternal, nor can a man take anything with him when he dies; nay, it is inevitable that he depart naked..." (Lucian, Vol. II, p.437)

Fake books. In some Menippean satires, these are promised to the reader (and never delivered). In variations, they are alluded to or cited as authorities, or whole libraries are invented (as Rabelais' Thélème). Mock erudition is one of the devices for satirizing academic or learned pretentiousness. Examples of this topic include: Harington's "tenth decad" of "the reverent Rabbles;" A Catalogue of Books of the Newest Fashion, "to be sold by Auction, at the Whigs Coffee-House, at the Sign of the Jackanapes, in Prating Alley" (included in The Harleian Miscellany, V.6); Thomas D'Urfey's An Essay Towards the Theory of the Intelligible World... (etc.); Burnet and Duckett's A Second Tale of a Tub: or, the History of Robert Powel the Puppet-Show-Man (they "refer the Dispute" - over whether the dead have sensation - "to my Eighteen Volumes in Folio coming out as a Comment upon Duns Scotus"); Johann Fischart's Catalogue Catalogorum perpetuo durabilis. Das ist: Ein Ewigwerende, Giordianischer, Pergamischer und Tirraninoschar Bibliotecken gleichwichtige und richtige Verzeichnuss und Registratur (1590), and countless others including the Obscure Epistolers, Erasmus, Swift, Sterne, Carlyle's Sartor Resartus and Finnegans Wake. Swift opens the Tale with a list of fake treatises, "which will be speedily published."

Fake Preface. Let this topic include all manner of fake prefatory and introductory material. The locus classicus for this topic is Swift's Tale: it presents the reader with a (digressive) dedicatory note "to the right Honourable John Lord Sommers" (by "the Bookseller," as the Tale was anonymous); a note from "the Bookseller to the Reader," citing Menippean relatives; "the Epistle Dedicatory, to His Royal Highness Prince Posterity" using the Senecan/Lucianic claim of truth; "the Preface," lengthy and digressive; and "Sect. 1 - the Introduction," lengthy, digressive, and replete with (fake) lacunae, citations and descriptions of fake texts. Sterne places a (digressive) dedication at the end of Vol. I, ch. VIII, and uses the next chapter to comment upon and slightly emend it: "... the rest I dedicate to the MOON, who... has most power to set my book a-going, and make the world run mad after it..." His "the Author's Preface" appears in Vol. III, ch. XX. See also D'Urfey's Essay: the section "Of Prefaces" is not a preface; near the end of the book a pointing hand indicates the centred message, "HERE ENDETH THE PREFACE."

Fake Table of Contents. This topic is of a piece with the preceding one and includes misplaced Tables of Contents (as in Du Cliche´ á l'Archetype: la Foire du Sens, where the chapters are in alphabetic order, and the Table under T). Principally, however, this topic refers to a Table of Contents that lies, that promises matter and chapters not in the book. D'Urfey sets out a prefatory table of contents for his Essay, announcing "sections" never to be found, or given in vastly different form.

Forcing the Reader to Think. This is basic to all Menippean strategy and derives from the Cynic demand to "wake up!" A sure means of accomplishing this is by challenging the reader's assumptions and by violating his expectations about narrative continuity, truthfulness, decorum of style, and literary conventions (e.g., that diagrams refer to textual matter, or that promises will be fulfilled). One means is Joco-Seriousness (q.v.), the expenditure of lavish erudition on trifles and vice-versa. Another means is using paradox (including paradoxical encomia) to involve and intrigue the reader, for intellectual detachment and reflection.

Gibberish. Properly one of the language topics, this includes nonsense words, phrases, sentences or paragraphs. The result can be hilarious. E.g., the scholarly labor thus far expended in attempts to decipher the "languages" in Gulliver's Travels are a Menippean "side effect" of that satire whereby the scholars' efforts and reports become an additional "chapter," in which they satirize themselves unwittingly and unmercifully (because they're not playing). Users range from Rabelais' "Corrective conundrums" (Gargantua, 2: gibberish punctuated by gaps), to Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky, to Finnegans Wake, which some critics argue is entirely gibberish, "a monstrous joke."

Glosses. This topic embraces fake glosses, false erudition, irrelevant glosses, and includes similar play with footnotes and other marginalia and "editorial" digression from the text. Examples: Lyly, The Owle's Almanacke (mock-serious marginalia), Swift, Dunton. Sterne used a variation by putting his characters into tableaux (his "Shandean way of writing") for sentences, paragraphs or even chapters at a time, so he could mount digressive hobby-horses. Joyce used it all in the "Triv and Quad" chapter of the Wake. Often fake and real are interspersed, leaving matters to the reader to sort out. Swift glossed the Tale with one of the Tale's critics' remarks. This topic is clearly related to Digressiveness.

Groping. There are several forms: one is for the "mot juste." Alternatively, the author either pretends to have lost his way, perhaps due to digressions, and to be unable to find it again (often in Sterne); or he pretends to reach for the ineffable and to lose it, while remarking to the reader that in any case no direct understanding is possible. Korkowski points out (p.281) that Beroalde goes a stage further in noting that his own work, which admits only of being a "moyen de parvenir" and not an actual arrival, "is more honest than other books which offer definitive statement but no comment on the lack of ontological certainty in reading and language":

"Sur quoy je vous diraiy un grand secret, et puis l'autre; c'est que vous ne trouverez point en cecy du truandage de pedantisme, comme des autres, pleins du ravaudage de folle doctrine qui n'aporte pointe á disner. Et davantage, je vous diray le secret des secrets; mais je vous prie, afin qu'il soit secret, de vous embeguiner Ie museau du cadenac de taciturnité, et ecoutez: CE LIVRE EST LE CENTRE DE TOUS LES LIVRES. (Le Moyen de Parvenir, p.32)

Honesty. "I promise you purest truth," followed by whopping lies. A basic and frequent topic, this includes all the varieties of misrepresentation, misleading and fakery. Lucian's True Story is the touchstone.

How to Read the Book. The reader is given clues or instructions by the author. A feature of most Menippean satires. E.g., Sterne Vol. I, ch 13 (instructions promised), Rabelais, Byron, Joyce.

Inability to Edit Anything Out (feigned, of course). This is related to such other topics as Catalogs and Encyclopedism. Examples: Harington, Sterne, Nashe, Swift.

Joco-seriousness--see Spoudogeloion.

Kidding or Teasing of a Female Reader. Digressive chitchat with female readers (of delicate sensibilities), which may include lines that the writer supposes will come from the reader. This topic is best exemplified in Beroalde and Sterne. Cf. Tristram Shandy I.vi; I.xviii, and passim, to "Sir," "your Lordships," "Madam," or "Dear Jenny." Cf. especially the thinly-veiled hints of sexual horseplay he gives her, at p.226, facing the Marbled page (Word, ed.). Beroalde litters the Moyen with such asides, as does Bouchet. Dunton does the same.

Lacunae. Cf. Digression. The fake lacuna, a form of caprice with narrative continuity and order, is used commonly by Menippeans to tease the reader (Cf. Beroalde, Swift, Sterne). Sterne is the handiest English paradigm. He used blank pages, black pages, marbled pages ("motley emblem of my work," III.xxxvi), and omitted chapters.

Carlyle used a new variation: he told the reader that the materials for the 'Autobiography with "fullest insight"' of Teufelsdrókh arrived in the editor's hands in six "considerable PAPER-BAGS, carefully sealed, and marked... with the symbols of the Six southern Zodiacal signs." These contained a hopeless jumble of assorted Sheets, Shreds and Snips on every imaginable trivial and inconsequential subject. (Sartor Resartus, ch.XI) D'Urfey is replete with chasms, even to a section titled "the Method of Making a Chasm or Hiatus, judiciously; the great Reach of thought requir'd for the Contrivance thereof, together with the Difference between the French Academies and the English."

Language. A variety of topics appear under this heading, which designates matters pertaining to the language found in Menippean satires.

Bad Language. Mis-users of language are often a target of Menippean satires: this is an aspect of the Menippists' relation to grammar and its concerns. Korkowski: "One particular fraternity pretending to learning that has incurred Menippean censure, regardless of periods, is the mis-users of language: the rigid grammarian, the sophist who deals in glittering speech, the hack poet, the fanciful etymologist, the word-torturer, and the 'systematizer' of language are the genuine bétes-noires of the Menippist... on the theme of correct language and in degree of linguistic brilliance, Menippism as a species of controversy has no equal in quality. Bonaventure Despérieres' Cymbalum Mundi, Beroalde de Verville's Moyen de Parvenir and Swift's Tale of a Tub are to the problems of words what the very greatest thinkers' works have been to problems of philosophy." (pp.61-62) Cf. Pope's Peri Bathous (part of the "Martinus Scriblerus" project that produced other, independent Menippean productions, e.g., Gulliver's Travels). Finnegans Wake uses every rhetorical and grammatical device known, and every resource of the language-as-storehouse-of-experience. Joyce noted that he had to "put the language to sleep" to obtain the necessary freedom. The linguistic hi-jinx of the Wake are not without precedent, however. Rabelais used the Menippean form of language-tinkering. Apuleius, Martianus Capella and Alan of Lille wrote the most playful (to a Menippean; "tortured" to the sober critic) Latin extant. Following Rabelais, Etienne Taburot published his Les Bigarrures, a playful and exhaustive tampering with the humorous possibilities of disrupting the ordinary conventions of logical structure, sentence structure, word ordering and even letter orders; puns, obscenities, parodies of printed symbols, and relentless para-logical hoppings from one word to some strange equivalent or associated term, occur. His displays, however, tend to be little more than catalogs, set out one after the other, of ingenious lingual transpositions. (Korkowski, p.267)

Deluding Word. Words' numinosity is related to the topic of their correct usage and is persistent in Menippean satire. (All of the language topics - chief Menippean concerns - show the direct relation of these satirists to grammar.) Cf. the Obscure Epistolers, Martianus Capella (the aptness of the marriage of Mercury and Philology - rhetoric and grammar), Alan of Lille's De Planctu.

Fake Etymologies. This kind of grammatical horseplay by Menippists satirizes the sober ineptitude, clumsiness or superficial learning of the dialectician who tries to take over grammar with logic and philosophy. Equally, it is used to lampoon the inept or unlearned grammarian. Mostly in use since the nominalist/realist debate, it is related to the definition or the absolute meaning, or the absolute nature of things. Cf., Beroalde, Despérieres, Rabelais, Sanford's Mirror of Madness, Swift (e.g., "Antiquity of the English Tongue"). Its use is frequently accompanied by a display of erudition (real or fake, or both) of authorities in support of or contending about the etymologies. "The abnihilization of the etym" (FW 353.22). Related to Nothing.

Gibberish as language (see above).

Letters of the alphabet, as things, as praised, blamed, at peace or at war with each other, etc. This topic occurs often, from Lucian (The Consonants at Law) to Joyce (FW 119-123). Punctuation is also a topic, similarly handled (FW 124, for example), as are parts of speech. Cf. Guarnas' Bellum Grammaticale, Sterne on verbs (copular; copulation) and "auxiliaries," Alan of Lille.

Mixed Languages. This topic refers to the use of more than one language in a text, perhaps without adequate (or any) justification. A form of digressiveness, it can be related to tactics of violating decorum, as each language embodies the perceptions and experiences of the user culture, and it can include fake language (as in Gulliver's Travels). Among others, Varro and Burton display polyglottism. Sterne provides Slawkenbergii Fabella at the outset of Vol. IV (Tristram Shandy), accompanied by a simultaneous translation on the facing pages that is six times as long as the Latin. Joyce inserted sections in Latin and in French into Finnegans Wake, in "Finneganese," and his puns and thunders use fifty or more languages.

Prose-Verse Mixture was used in antiquity as the hallmark of Menippean satire and is still adhered to as a sine qua non by many classicists and critics. A digressive technique related structurally to both etymologies of satire, the mixing of verse with prose constituted a violation of decorum calculated to shock the sensibilities of the percipient reader or hearer into alertness. It is often combined with Joco-Seriousness (and related topics) as high style is employed on base matters, and vice-versa. A variation was the sprinkling, through a prose text or dialog, of lines and verses misappropriated (and misapplied, used on quite different subjects) from ancient or epic poets. Cf. Lucian's Charon.

Words as Gestures, and vice-versa. Words and language are used on a supra-semantic level where they shed their "contents" of usual meanings and function as eloquent acts. This topic is an aspect of all Menippean language-tinkering: the prime example is Joyce's thunders. For the reverse, gestures as words, see Rabelais, Gargantua 2; Pantagrual 19. In either variation it is a form of digression from normal accidence and syntax.

Words as Things, and vice-versa. The preceding topic draws attention to eloquence inherent in the formal character of utterance: this topic deals with the relation between language and artefacts. Both topics are grammatical and formal; though serious, this device is most often used ludicrously. Cf. Swift, Gulliver's Travels, Tale of a Tub. Things-as-words (or events) stand in direct relation to the Medieval grammarian's techniques of exegesis of the Liber Natura, a parallel text to the Liber Scriptura, echoes of which survive and persist in the poets. Cf. Don Juan, III.88 (note the Menippean-Cynic tone):

"But words are things, and a small drop of ink, Falling like dew, upon a thought, produces That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think; T'is strange, the shortest letter which man uses Instead of speech, may form a lasting link Of ages; to what straits old Time reduces Frail men, when paper - even a rag like this, Survives himself, his tomb, and all that's his."The written or printed word is a thing, inarticulate in itself.

Laughter. Laughter may be Democritean (e.g., Lucian and Burton), Diogenical (e.g., Rabelais), Wakean ("Lots of fun at Finnegans Wake") or routinely Cynic-Menippean. Both a topic and a tactic, laughter is indispensable to Cynic joco-seriousness, to retuning the reader's sensibilities by means of an engendered playfulness, and to curing him of undue or misplaced sobriety. In this regard it is related to topics of Digressiveness and of violations of decorum. Bakhtin has this as the quintessence of carnivalism, which he identifies with Menippism. Burton resounds with Democritus' laughter. Cynic laughter and wit runs through Beroalde, who notes in his first chapter that he directs laughter at the philosophers "because mirth must be restored." There's "lots of fun at Finnegans wake."

Learning. Cf. Encyclopedism, Fake Books. Respect for maintenance of the traditions (grammatical) of genuine learning and encyclopedic wisdom is concealed under attacks on all forms of easy, simplified or systematized "learnedness," pseudo-intellectual and philosophical extremism and universalising. Examples: Menippus, Varro, Petronius, Seneca, Lucian, Erasmus, Rabelais, Swift, Flaubert, Joyce. The Scriblerians (Pope, Arbuthnot, Swift, Gay) aimed to produce periodically a Works of the Unlearned: Flaubert got somewhat farther with the project with Bouvard. Cf. Sterne on noses (gnosis).

Medicinal. This topic is related both to the sanative powers of satire in general, and to those of Menippean satire in particular. Menippean authors frequently refer to their satires as having curative properties. This can range from generalities, such as "Written for the Universal Improvement of Mankind" (Swift, title page of the Tale, spoofing the gloriosi), to more pointed claims that the work is a "medicine," as in Rabelais, or in Burton, or Dekker:

"… more potent, and more precious, than was ever that mingle-mangle of drugs which Mithridates boyld together. Feare not to tast it... the Receipt hath beene subscribed unto, by all those that have to do with Simples, with this moth-eaten motto: Probatum est: your Diacatholicon aureum... pledge me, spare not... take a deep draught of our homely counsel." - Dekker, The Guls Horne-Booke (Non-Dramatic Works, Vol. II, pp.213-214)Memory of Time before Birth. The author discusses (as a spectator) events that occurred before his birth. Sterne (Tristram Shandy is not born until well into the third book) presents a mass of irrelevant detail on the events that preceded and surrounded both his narrator's conception and his birth. Dunton rambles through memoirs of his earliest years, including the years before he was born: chapter one of Vol. I treats "Of my Rambles before I came into my Mother's Belly, and while I was there." His rambling narrator, Kainophilus, adds a twist to the theme, complaining that he made no notes on the moment of his birth (though he made, somehow, plenty of notes in utero) as he was born without anything to write with - in fact, "Because I was dead born, I can't remember anything on it to save my life."

Method. Dialectical systematizing and universalizing is a common butt of Menippists, and as such continues the grammarians' attacks in the battle of Ancient vs. Modern. Cf. the Cynic disdain for all forms of easy or systematic (abstract) answers to any of life's problems, which result in the individual not thinking for himself. E.g., Swift spoofs the gloriosus lightly in presenting the Tale "for the Universal Improvement of Mankind," and savagely in the stupidity of his hack. Sterne lightly but thoroughly dissects Locke, Carlyle the German gloriosi. The structure of Burton's Anatomy parodies post-Ramist branched-logic systems. Cf. Moderns.

Mock Eulogy. Taken directly from epideictic rhetoric and the topics of laus et vituperatio, the paradoxical encomium goes back at least as far as Gorgias' Praise of Helen. Just at what point this enters Menippean lists is hard to say. One of Varro's Menippean satires has the title, "Two asses will praise each other" - Mutuum muli scabunt. Lucian wrote many mock-eulogies, e.g., Phalaris I and II, Peregrinus, Alexander, Saltatio and Muscae Laudatio. Cf. also Erasmus' Praise of Folly, Panurge's "Praise of Debtors" (in Le Tiers Livre, ch. 22), the "harangues" of La Satyre Menippée (1594), Burton's Anatomy (III.2.l.l), Swift's praise of Madness in the Tale, Nashe's praise of the red herring in Lenten Stuffe. Further examples in Rabelais and others are discussed in Colie, Paradoxia Epidemica. Sterne is careful always to praise Locke while he demolishes his theories. Korkowski notes that "after Lucian (and even before him) the satirical eulogy is identified with this Menippean tradition by knowledgeable authors. To men of the Renaissance, for example, Lucian's mock-praises appeared germane to snarling Cynicism; almost anything by Lucian, for that matter, was regarded as proceeding from a common Menippus-Lucian temperament... That the mock-encomium and 'other' Menippean forms were perceived as identities can be gathered from Erasmus' epistle to Thomas More, introducing the Praise of Folly..." (p.98)

Moderns. The "moderns," or dialecticians (gloriosi) in all ages, are a target of Menippists. The line of attack runs through Menippus, Varro, Petronius, Lucian (e.g., The Sale of Philosophers), Erasmus, Cervantes, Rabelais, Voltaire, Butler, Dekker, Nashe, Swift, Sterne, Carlyle, Flaubert and Joyce. Cf. Method.

Musical Notation. The verses interspersed with the prose frequently have the potential of being used independently as songs. However, this topic refers particularly to an interruption of the running text by offering the reader the notes and musical notation of songs, with or without the verses, and which may or may not be musical or euphonious. Examples include Bishop Francis Godwin's (1638) The Man in the Moon (the moon-giants discourse in a wordless language of music made up of standardized tunes, several pages of which are presented to the reader as a message of moment to Englanders) and Cyrano de Bergerac's Histoire Comique des Etats et Empires de la Lune et du Soleil (his moon-people are like Godwin's: they speak a language of tunes that appears in the text as musical notation). Korkowski notes (p.330), "this was not new in Menippean satire" and refers the reader to the Sermo Quodlibeticus de Podagrae Laudibus in Dornavius, and Taburot's Bigarrures for precedents. Harington includes pages of music in Ajax. Joyce includes the written melody for "The Ballad of Persse O'Reilly" in Finnegans Wake (pp.44-47), and two other written melodies in the "Ithaca" chapter of Ulysses.

Mutilated Text. The author, either as himself or in the person of a publisher or editor or critic, presents or comments upon a text that he claims is corrupted, mutilated or otherwise interrupted by lacunae. See Lacunae.

Natural Scale. Inseparable from the other Cynic topics, this one refers to Cynic insistence on not exceeding the limits of human scale, which includes constant attention to our human frailties, limitations, susceptibilities to pride, self-aggrandizement, and so on. In Menippean satire, this is an aspect of the Cynic wind that blows through the satire as much as it is an aspect of the purposes of the satire. The reader's sensibilities are to be so revivified that he becomes aware of his deviation from, and will develop a preference for restoring, human or natural scale in his activities, psychic and social.

Non-sequitur. Deliberately used by Menippists, the non-sequitur is related to lacuna-making, digressiveness and all forms of interruption of narrative sequence, q.q.v. Non-sequiturs are the order of Beroalde's book. To make his reader aware that "straight-line" narration is a purely arbitrary order, Sterne, sending up Locke, denies his reader what is expected, interrupts the continuity of narrative logic at every turn, displays the pieces, and then asks innocently what they are and how they should go back together. In Ulysses, Joyce found new variation on this topic in the technique of "simultaneous parallels" with Homer, as well as in the discontinuities of "stream of consciousness."

Nothing. This topic, a frequent subject in Menippean satires, includes writing on recondite trivialities ("nothings"), often with a display of immense erudition, or, literally, writing whole chapters on "nothing." This latter is related to satirizing gloriosi logic-choppers who cut matters so fine that their weighty systems are brought to bear on "nothings." Dunton's Voyage offers "admirable and surprizing Novelty of both Matter and Method; a Book made, as it were, out of nothing, and yet containing every thing..." Ulysses and Finnegans Wake may equally be said to be made of "nothings" and yet to "contain everything." Cf. also Nashe, Sterne. Most Menippeans try their hand at this topic at one time or another as sustaining it calls for high wit and inventiveness. Swift: "I am now trying an experiment very frequent among modern authors; which is, to write upon nothing; when the subject is utterly exhausted, to let the pen still move on; by some called the ghost of wit, delighting to walk after the death of its body..." (etc., from the "Conclusion" to the Tale). Rabelais lavishes formidable amounts of attention upon bagatelles (as does Macrobius on the egg, and Athenaeus on odd kinds of fish). Panurge's decision to marry, for another example, becomes the focus of an enormously prolonged, prolix and pettifoggish debate leading to nothing.

Parody of New Forms. The chameleon-like and mimetic nature of Menippean satire, which contributes to the impossibility of accounting for it descriptively, gives it immense flexibility and adaptability to new forms and new situations. As soon as new genres or modes or media for expression appear, Menippists quickly adapt to the new form and begin to explore its satirical possibilities. This was done, for example, by Rabelais, Nashe, Dekker and Aretino, as Korkowski points out (p.225). Rabelais puts on the pretensions of the new "learned" genres made popular by printing. Somewhat later, Swift creates hiatuses with a new symbol, the asterisk, and Sterne toys with all the devices of the book, even to turning it inside out by putting the marbled end-papers in the middle. Flaubert aped the popular press in declaring his ideal novel would be all style and no content. Joyce used cinematic technique in Ulysses and remarked that the Wake was written "after the style of television." The study of Menippism in modern media has not yet begun. I suggest that there is no reason why it should not have expanded beyond the confines of written or printed texts once audiences were formed by and could be hypnotized by other-than-literate media. One might begin such a study with Orson Welles (Radio), Woody Allen (Film), and Steve Allen or Norman Lear (Television). The mind boggles at what havoc a determined (Cynic) Menippean might wreak with the telephone, or computer data-bases and systems analysis, or satellites. We may yet find out. See Printing.

Philosophus Gloriosus. He is the favorite Menippean whipping-boy. Philosophers (dialecticians) are open to Menippean attack on several grounds. First, their whole enterprise is traditionally based upon abstraction of ideas and reasoning, which the Menippist can castigate as a form of undue exaggeration and equally as a retreat from reality. Second, their reliance on logic as a tool and the fine distinctions and rare abstraction into which that often leads also fuels the Menippean fire. The grammatical side of Menippean satire would have at the gloriosi in any case, as a skirmish in the quarrel of Ancient with Modern. Those are general terms: particular targets are more usually members of fashionable and pseudo-intellectual groups, as in Seneca's Apocolocyntosis (the ignoramus Claudius and his retinue of hack poets) or Petronius' Satyricon, or in Erasmus or Lucian, in Hudibras, or Tristram Shandy. Swift sent up one group in the Tale, quite another (the equivalent of the mad scientist) in Gulliver. Carlyle takes aim at the invasion of German philosophy in Sartor Resartus (tailors are second only to philosophers as Menippean targets), and Wyndham Lewis at Bloomsbury pretentiousness in his Apes of God. The pseudo-learned of all sorts are the favorite quarry: these fakes - the real gloriosi - have usurped the place of the genuinely learned, have bamboozled the less educated, and have used the appearance of learning and wisdom for worldly gain. They are as thieves and polluters. In our time, the bestseller writer is as much a gloriosus as was Locke in Sterne's.

Printing Conventions Trifled With. Cf. Parody, above. This topic concerns horseplay with the conventions of printed books. Practitioners include Rabelais, Nashe, Harington, Sterne, Joyce. In a variant, Rabelais (as Swift, etc.) claimed that his text had been botched by incompetent printers (a common enough complaint even now by authors): "For the benefit of the warriors I am about to rebroach my cask, the contents of which you would sufficiently have appreciated from my two earlier volumes if they had not been adulterated and spoiled by dishonest printers..."

Projectors as targets. This refers principally to the mad scientists and crazed philosophers of Swift's time (Cf. Philosophus Gloriosus): they seem to be accounted as of the same family as astrologers, alchemists, etc. Swift's "Grand Academy of Lagado" has an ancestor in Joseph Hall's Mundus alter et idem, an account of travels to and the fabulous goings-on at "Terra Australia Incognitis." The most populous region of Australia, Fooliana, has a university, called "whether-for-a-pennia," where specimen sciences are taught, including penny astrology. In one college, "Gewgawiasters" are busy inventing a way to blow soap bubbles from walnut shells: they have also invented projects and novelties in "games, buildings, garments and governments," and have devised a new language, the "Supermonicall tongue."

Reader. He is the real target of Cynic Menippism. The reader is kidded, cajoled, threatened, flattered, etc. by turns, and if the satire is successful he will enter into or put on the spirit of the work. Frequently, the author himself (or wearing one or another narrator's persona) will engage in lively discourse with the reader on any topic that comes to mind, including the right arrangement of the book, the reader's habits or his dress, etc. Like Swift before him, and Sterne after, D'Urfey's Gabriel John empowers his reader to transpose things to his own liking (in the section "Which end of a Book to begin at"). As Finnegans Wake is written in a circle, the reader can begin anywhere. Joyce expected his reader to abandon all other pursuits and devote full time to studying the Wake. Rabelais makes the same demand:

"I intend every reader to lay aside his business, to abandon his trade, to relinquish his profession, and to concentrate wholly upon my work. Rapt and absorbed, all might then learn these tales by heart, so that if ever the art of printing perished and books failed, these tales might be handed down, like mystic religious lore, through our children to posterity! Is there not greater profit in them than a rabble of critics would have you believe?" (Prologue to the Second Book)Evidently, Menippists, like the Cynics, regard "staying awake" as a full-time business.

Simultaneity of Past and Present. The cast of characters in a Menippean satire will often include persons widely separated by chronological time. Linear, chronological time may be circumvented by a device such as setting the scene in the afterworld (Dialogs of the Dead, etc.) or may simply be ignored altogether as in Beroalde's Moyen de Parvenir, in some of Landor's Imaginary Conversations, in Pound's Cantos, and in Finnegans Wake, to mention but four. This same attitude to the irrelevancy of mere chronology was present in the translatio studii of the grammarians, and marks another affinity between their enterprise and the Menippean one. As already pointed out, this topic is also implicit in the mimetic nature of Menippean satire. In our time it has received explicit statement in T.S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual Talent," and has been used extensively in his poetry, notably in "The Waste Land" and in Four Quartets.

Spoudogeloion. Cf. Joco-seriousness.

Tailors. Tailors are common as the butts of Menippean satires; in some periods they are second only to philosophers as objects of attention. Carlyle mounts a combined attack in Sartor Resartus. Tailors receive attention via Cynic attacks on pomposity and pretentiousness, for covering up bodily defects or for taking attention away from real matters to waste it on illusory corporal beauty - a kind of seduction. Diogenes wore his tub; Dunton has his Parable of the Top-Knots; Swift his Shoulder-Knots. Satires on tailors are to be found in L'Estrange's Quevedo and in Greene's and Dekker's treatments of tailors in Hell. (Dekker weighed the old world's tailors and the new together in The Guls Horne-Booke.) In the Wake, Joyce explores the seduction-via-clothing theme with his Prankquean, and riots with the story of Kersse the tailor trying to fit a suit to a hunch-backed Norwegian ship's captain.

Talking Animal. Korkowski notes (p.170, n.49) that "the talking animal, in ancient literature, hardly appears outside of Menippean writings (i.e., Lucian's Gallus, Apuleius' ass, Plutarch's Gryllus)." In Menippean satires, anything and everything, including animals, and even words or letters, may give voice. In the Circe chapter of Ulysses, speeches are delivered by a gong, a bar of soap, wreaths, gulls (birds, not fools), a timepiece, the quoits of a brass bed, bells, chimes, a crab, a hollybush, bronze buckles, a cap, a gramophone, a gas-jet, a doorhandle, a fan, a hoof, the sins of the past, Sleepy Hollow, Yews, a waterfall, halcyon days, a mummy, characters' voices, Orange Lodges, a pianola, bracelets, "the hue and cry," the voices of "all the damned" and "all the blessed," and a horse.

Tradition. Tradition may be singled out as object of attack: the Menippist impersonates an enemy of (grammatical) tradition, of the Ancients, and bungles the job. Cf. Dekker (The Guls Horne-Booke) and Swift in his "Digression in praise of Digressions."

Universalizing. Glib universalizing appears as the butt of many satires. Cf. Philosophus Gloriosus above. Practitioners include Cynics, Lucian, Rabelais, Swift, Von Hutten, Erasmus, Flaubert.

Universal Schemes (treated variously, above). This refers to Menippean mockery of dialectical or scientific universalizing by projecting crazy schemes of their own, as in Sanford's Mirrour of Madnes, Swift's Modest Proposal or his "Digression concerning the original, the use and improvement of madness..." (which derives from Sanford). Such schemes are proposed, as are many of the satires, "for the universal improvement of mankind." Rabelais and Cervantes are thoroughgoing and merciless, as is Flaubert.

Whatever enters my head. An aspect of the autonomous author, this topic is related to pretended inability to manage a discourse. Seneca has: "dicam quod mihi in buccam venerit." A host of others followed suit, including Burton, D'Urfey, Sterne and the writers of Finnegans Wake (the public, the users of the language whom Joyce patiently studied).

![et cetera : LOVE [1977]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQ8s7vwLQuzHDNgqlfBacxRkEbOErToak9kmgFl0VmyIYEqS9qIzNIVcXKpzTncPhqo3TSgOyztAguIW6OlXw65aFHmpx6cRzmvCUQQMTwUGUOd0iE0GbJakEc3g3kBAJrvlZP4z3eesg/s1600/etc1977.jpg)

![MAC LUHAN [sic] : LOST IN TRANSLATION](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg92tMqBMDA917NDivsS2ZwIirx9KTf24tOCgFFnK65p7Hw5dvqEh1e2aefCynj2UW8u-k8zwBXbjgypsCXUcv-5G7ZCsyDB13giHEjmhVISAeW-oI_JV6ePOXW_XBDPwy2nREAoqRU7Z8/s1600/MAC.jpg)

![Les Yeux De Nadja [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgrXohpIuxxYyjKoqBSQf3TpYGjnttZnjRFvmMdshadfnVKi7PMAjIqEuqYctZFXOFH2n-oH75oJx-YkaON7xvaZgVdvaK0zfSOurEmCKqmWF6qXh2F3VbqyixfGhvY4qH6LENMTs1wCIw/s1600/2xsurreal.jpg)

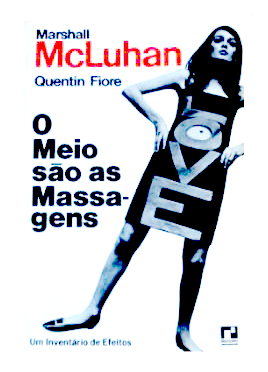

![PIED PIPERS [MARSH] ALL](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqvGIGG9lWZYhFZRVc_V8EJG2apQBsys4kNQOQsA0EV6H6Tg-SMN0sX15NXy_GzsF3xAUdcb2QlfvJk-RU-Rha-3Eu5Mnglkf5KLe6pccVqAP4VR_Gi4fGQ716QSmDe3Zna5Uwct5d2sw/s1600/piedPiperMarshALL270.png)

![PICNIC IN SPACE : The Great Minds of Our Time Film Series [1973]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyov75DRIUBWcYLkzPYmupFy8CQ9dQ4Q798zDIN6jPNsSdBB_WuOcvPl4WjMAz10csG071oCO3BCUtIcKyHoIkCN0lCy0OxGCV_HrLXrGNKRpUiKMrqzkJh4LSc7jT_KrrqmClapSlVa8/s1600-r/PicnicInSpace.jpg)

![more Hidden ground [re:Bride] : the "flippancy" of tone seemed just "right"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg-hQyF9KGGhKYc73nUGmV1bStJ4fTJVh0-TL1ZtikLZEv5ppjhB3DOhFcVuzGq-kByrwtTAWgCcE173pA3UTIPe7h6xJjsPt7lRvNym007ZsdXenMDLNimKcwtaTOqkGleoxmXOeCKtxXL/s1600-r/LEAVISLEWIS.png)

![BABA WAWA [TODAY SHOW, Toronto City Hall 1970]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTZAIFkA07K36WGk951vmZnLPU99fOdNzlvVhyphenhyphenhKZEKu2n2AW5EA1CDZGaTk0aYRXUv7IOXG39igaikoE6SWm8j7QIG96wYRE54oBXwvlaNCJzp15vdkrcqR97IMMny-8sHjM-VDotTOaY/s1600-r/babaWawa.jpg)

![enter the dragon : "typhon in america" [unpublished]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdCnZdJ6JbaLc6hyUmUJo5UJ0m8WZSj_afYU9oRlHKIUgAIfcy2EPHNAptSRYEAmpOf0Xaa0B8iMgOTF302lY0Xmbyne0hvrdRyNo-t0Q-PPdzqX39uI3T5x5FppRPaQf9sSaXytrOpWVN/s1600-r/TIA.jpg)

![Take Today [1972] : "the consumer becomes a producer..."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhA53bdVdTaXdQo1fDmrsI8oiAwF-3jampcanOq8uk3QMh8_ImkNsTiKd4-RnZY8Vbwqh1fymJiyCl1CSLcSonXHQM6XbnJYQi_Vu89gbAV4jVq73EtlbM3w6CthyphenhyphenV_pHEjE6eu_VhC489u/s1600-r/PROSUMER.jpg)

![" Outtragedy of poetscalds!, Acomedy of letters " [ FW 425.24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJMrJLN3oPUb25A2tjQtWZcZxA4wZB0IOvaIAvxosAUqlFc258HHvzvlnHHvKhKq7hG3epo76izY2Bu0HC3Cy-8S46Rf0Wni3L8j8jEfpT7sXK3UFlXBMtN2v2JdrmdxvWk8VWKjkhN4-9/s1600-r/preplexLP.png)

![mars[HAL]9000 : " Tomorrow is our permanent address."](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhmblupqmUiuV3GbyayJiDRGEO63TEgwjHi-i8b0kVYDvXrKFWTCyl-e21la4QJXC4nDFDzx51Omi6fYPLJcqRHFoP6zSsL0CVZF98eMf6mxCE2WDfvMmT4q9G3X45-P0IYGDmliE0fCR3C/s1600-r/marsHAL9000_250.jpg)

![Lucifer [from Latin] <br>meaning "light-bearer"](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq-2kZZOfh-Syv1Ewa0Ns2O6ZeP59pcsJp9ihhKcXCaovYZO_cKxffC5iSKOXFHr6E1jiHc6zedt1U6I95831RgpVdm3qk8-9C3y1yPyrCiQe4jgx-DsbeHnjKnw9t6Qx3ZM5TSYxiPj5H/s1600-r/lucifer.png)

3 comments:

There is a kind of illusion in the world we live in that

communications is something that happens all the time, that it’s

normal. And when it doesn’t happen, this is horrendous. Actually,

communication is an exceedingly difficult activity. In the sense of

a mere point-to-point correspondence between what is said, done,

and thought and felt between people—this is the rarest thing in

the world. If there is the slightest tangential area of touch,

agreement, and so on among people, that is communication in a

big way. The idea of complete identity is unthinkable. Most

people have the idea of communication as something matching

between what is said and what is understood. In actual fact,

communication is making. The person who sees or heeds or hears

is engaged in making a response to a situation which is mostly of

his own fictional invention. What these critics reveal is that the

mystery of communication is the art of making.

McLuhan, “The Hot and Cool Interview,” 69.

McLuhan deliberately violates accepted rules, by eliminating “verbal road signs,” which lets “thoughts crash into each other head on.” Consequently, much of McLuhan’s prose lacks the connecting statement. Rather, discontinuity is a central organising principle in his work – and that once one understands continuity and discontinuity the reader will be able to understand not only McLuhan but Salvador Dali. Like Dali, in McLuhan we see how the seemingly unrelated share the same space.

- Eugene Schwartz, “A Second Way to Read War and Peace in the Global Village Or McLuhan Made Linear,”

MANIFESTO

OF

SURREALISM

BY

ANDRÉ BRETON

(1924)

So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life ? real life, I mean ? that in the end this belief is lost. Man, that inveterate dreamer, daily more discontent with his destiny, has trouble assessing the objects he has been led to use, objects that his nonchalance has brought his way, or that he has earned through his own efforts, almost always through his own efforts, for he has agreed to work, at least he has not refused to try his luck (or what he calls his luck!). At this point he feels extremely modest: he knows what women he has had, what silly affairs he has been involved in; he is unimpressed by his wealth or his poverty, in this respect he is still a newborn babe and, as for the approval of his conscience, I confess that he does very nicely without it. If he still retains a certain lucidity, all he can do is turn back toward his childhood which, however his guides and mentors may have botched it, still strikes him as somehow charming. There, the absence of any known restrictions allows him the perspective of several lives lived at once; this illusion becomes firmly rooted within him; now he is only interested in the fleeting, the extreme facility of everything. Children set off each day without a worry in the world. Everything is near at hand, the worst material conditions are fine. The woods are white or black, one will never sleep.

But it is true that we would not dare venture so far, it is not merely a question of distance. Threat is piled upon threat, one yields, abandons a portion of the terrain to be conquered. This imagination which knows no bounds is henceforth allowed to be exercised only in strict accordance with the laws of an arbitrary utility; it is incapable of assuming this inferior role for very long and, in the vicinity of the twentieth year, generally prefers to abandon man to his lusterless fate.

Though he may later try to pull himself together on occasion, having felt that he is losing by slow degrees all reason for living, incapable as he has become of being able to rise to some exceptional situation such as love, he will hardly succeed. This is because he henceforth belongs body and soul to an imperative practical necessity which demands his constant attention. None of his gestures will be expansive, none of his ideas generous or far-reaching. In his mind?s eye, events real or imagined will be seen only as they relate to a welter of similar events, events in which he has not participated, abortive events. What am I saying: he will judge them in relationship to one of these events whose consequences are more reassuring than the others. On no account will he view them as his salvation.

Beloved imagination, what I most like in you is your unsparing quality.

There remains madness, "the madness that one locks up," as it has aptly been described. That madness or another?. We all know, in fact, that the insane owe their incarceration to a tiny number of legally reprehensible acts and that, were it not for these acts their freedom (or what we see as their freedom) would not be threatened. I am willing to admit that they are, to some degree, victims of their imagination, in that it induces them not to pay attention to certain rules ? outside of which the species feels threatened ? which we are all supposed to know and respect. But their profound indifference to the way in which we judge them, and even to the various punishments meted out to them, allows us to suppose that they derive a great deal of comfort and consolation from their imagination, that they enjoy their madness sufficiently to endure the thought that its validity does not extend beyond themselves. And, indeed, hallucinations, illusions, etc., are not a source of trifling pleasure. The best controlled sensuality partakes of it, and I know that there are many evenings when I would gladly that pretty hand which, during the last pages of Taine?s L?Intelligence, indulges in some curious misdeeds. I could spend my whole life prying loose the secrets of the insane. These people are honest to a fault, and their naiveté has no peer but my own. Christopher Columbus should have set out to discover America with a boatload of madmen. And note how this madness has taken shape, and endured.

It is not the fear of madness which will oblige us to leave the flag of imagination furled.

The case against the realistic attitude demands to be examined, following the case against the materialistic attitude. The latter, more poetic in fact than the former, admittedly implies on the part of man a kind of monstrous pride which, admittedly, is monstrous, but not a new and more complete decay. It should above all be viewed as a welcome reaction against certain ridiculous tendencies of spiritualism. Finally, it is not incompatible with a certain nobility of thought.

By contrast, the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit. It is this attitude which today gives birth to these ridiculous books, these insulting plays. It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog?s life. The activity of the best minds feels the effects of it; the law of the lowest common denominator finally prevails upon them as it does upon the others. An amusing result of this state of affairs, in literature for example, is the generous supply of novels. Each person adds his personal little "observation" to the whole. As a cleansing antidote to all this, M. Paul Valéry recently suggested that an anthology be compiled in which the largest possible number of opening passages from novels be offered; the resulting insanity, he predicted, would be a source of considerable edification. The most famous authors would be included. Such a though reflects great credit on Paul Valéry who, some time ago, speaking of novels, assured me that, so far as he was concerned, he would continue to refrain from writing: "The Marquise went out at five." But has he kept his word?

If the purely informative style, of which the sentence just quoted is a prime example, is virtually the rule rather than the exception in the novel form, it is because, in all fairness, the author?s ambition is severely circumscribed. The circumstantial, needlessly specific nature of each of their notations leads me to believe that they are perpetrating a joke at my expense. I am spared not even one of the character?s slightest vacillations: will he be fairhaired? what will his name be? will we first meet him during the summer? So many questions resolved once and for all, as chance directs; the only discretionary power left me is to close the book, which I am careful to do somewhere in the vicinity of the first page. And the descriptions! There is nothing to which their vacuity can be compared; they are nothing but so many superimposed images taken from some stock catalogue, which the author utilizes more and more whenever he chooses; he seizes the opportunity to slip me his postcards, he tries to make me agree with him about the clichés:

The small room into which the young man was shown was covered with yellow wallpaper: there were geraniums in the windows, which were covered with muslin curtains; the setting sun cast a harsh light over the entire setting?. There was nothing special about the room. The furniture, of yellow wood, was all very old. A sofa with a tall back turned down, an oval table opposite the sofa, a dressing table and a mirror set against the pierglass, some chairs along the walls, two or three etchings of no value portraying some German girls with birds in their hands ? such were the furnishings. (Dostoevski, Crime and Punishment)

I am in no mood to admit that the mind is interested in occupying itself with such matters, even fleetingly. It may be argued that this school-boy description has its place, and that at this juncture of the book the author has his reasons for burdening me. Nevertheless he is wasting his time, for I refuse to go into his room. Others? laziness or fatigue does not interest me. I have too unstable a notion of the continuity of life to equate or compare my moments of depression or weakness with my best moments. When one ceases to feel, I am of the opinion one should keep quiet. And I would like it understood that I am not accusing or condemning lack of originality as such. I am only saying that I do not take particular note of the empty moments of my life, that it may be unworthy for any man to crystallize those which seem to him to be so. I shall, with your permission, ignore the description of that room, and many more like it.

Not so fast, there; I?m getting into the area of psychology, a subject about which I shall be careful not to joke.

The author attacks a character and, this being settled upon, parades his hero to and fro across the world. No matter what happens, this hero, whose actions and reactions are admirably predictable, is compelled not to thwart or upset -- even though he looks as though he is -- the calculations of which he is the object. The currents of life can appear to lift him up, roll him over, cast him down, he will still belong to this readymade human type. A simple game of chess which doesn't interest me in the least -- man, whoever he may be, being for me a mediocre opponent. What I cannot bear are those wretched discussions relative to such and such a move, since winning or losing is not in question. And if the game is not worth the candle, if objective reason does a frightful job -- as indeed it does -- of serving him who calls upon it, is it not fitting and proper to avoid all contact with these categories? "Diversity is so vast that every different tone of voice, every step, cough, every wipe of the nose, every sneeze...."* (Pascal.) If in a cluster of grapes there are no two alike, why do you want me to describe this grape by the other, by all the others, why do you want me to make a palatable grape? Our brains are dulled by the incurable mania of wanting to make the unknown known, classifiable. The desire for analysis wins out over the sentiments.** (Barrès, Proust.) The result is statements of undue length whose persuasive power is attributable solely to their strangeness and which impress the reader only by the abstract quality of their vocabulary, which moreover is ill-defined. If the general ideas that philosophy has thus far come up with as topics of discussion revealed by their very nature their definitive incursion into a broader or more general area. I would be the first to greet the news with joy. But up till now it has been nothing but idle repartee; the flashes of wit and other niceties vie in concealing from us the true thought in search of itself, instead of concentrating on obtaining successes. It seems to me that every act is its own justification, at least for the person who has been capable of committing it, that it is endowed with a radiant power which the slightest gloss is certain to diminish. Because of this gloss, it even in a sense ceases to happen. It gains nothing to be thus distinguished. Stendhal's heroes are subject to the comments and appraisals -- appraisals which are more or less successful -- made by that author, which add not one whit to their glory. Where we really find them again is at the point at which Stendahl has lost them.

We are still living under the reign of logic: this, of course, is what I have been driving at. But in this day and age logical methods are applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest. The absolute rationalism that is still in vogue allows us to consider only facts relating directly to our experience. Logical ends, on the contrary, escape us. It is pointless to add that experience itself has found itself increasingly circumscribed. It paces back and forth in a cage from which it is more and more difficult to make it emerge. It too leans for support on what is most immediately expedient, and it is protected by the sentinels of common sense. Under the pretense of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices. It was, apparently, by pure chance that a part of our mental world which we pretended not to be concerned with any longer -- and, in my opinion by far the most important part -- has been brought back to light. For this we must give thanks to the discoveries of Sigmund Freud. On the basis of these discoveries a current of opinion is finally forming by means of which the human explorer will be able to carry his investigation much further, authorized as he will henceforth be not to confine himself solely to the most summary realities. The imagination is perhaps on the point of reasserting itself, of reclaiming its rights. If the depths of our mind contain within it strange forces capable of augmenting those on the surface, or of waging a victorious battle against them, there is every reason to seize them -- first to seize them, then, if need be, to submit them to the control of our reason. The analysts themselves have everything to gain by it. But it is worth noting that no means has been designated a priori for carrying out this undertaking, that until further notice it can be construed to be the province of poets as well as scholars, and that its success is not dependent upon the more or less capricious paths that will be followed.

Freud very rightly brought his critical faculties to bear upon the dream. It is, in fact, inadmissible that this considerable portion of psychic activity (since, at least from man's birth until his death, thought offers no solution of continuity, the sum of the moments of the dream, from the point of view of time, and taking into consideration only the time of pure dreaming, that is the dreams of sleep, is not inferior to the sum of the moments of reality, or, to be more precisely limiting, the moments of waking) has still today been so grossly neglected. I have always been amazed at the way an ordinary observer lends so much more credence and attaches so much more importance to waking events than to those occurring in dreams. It is because man, when he ceases to sleep, is above all the plaything of his memory, and in its normal state memory takes pleasure in weakly retracing for him the circumstances of the dream, in stripping it of any real importance, and in dismissing the only determinant from the point where he thinks he has left it a few hours before: this firm hope, this concern. He is under the impression of continuing something that is worthwhile. Thus the dream finds itself reduced to a mere parenthesis, as is the night. And, like the night, dreams generally contribute little to furthering our understanding. This curious state of affairs seems to me to call for certain reflections:

1) Within the limits where they operate (or are thought to operate) dreams give every evidence of being continuous and show signs of organization. Memory alone arrogates to itself the right to excerpt from dreams, to ignore the transitions, and to depict for us rather a series of dreams than the dream itself. By the same token, at any given moment we have only a distinct notion of realities, the coordination of which is a question of will.* (Account must be taken of the depth of the dream. For the most part I retain only what I can glean from its most superficial layers. What I most enjoy contemplating about a dream is everything that sinks back below the surface in a waking state, everything I have forgotten about my activities in the course of the preceding day, dark foliage, stupid branches. In "reality," likewise, I prefer to fall.) What is worth noting is that nothing allows us to presuppose a greater dissipation of the elements of which the dream is constituted. I am sorry to have to speak about it according to a formula which in principle excludes the dream. When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers? I would like to sleep, in order to surrender myself to the dreamers, the way I surrender myself to those who read me with eyes wide open; in order to stop imposing, in this realm, the conscious rhythm of my thought. Perhaps my dream last night follows that of the night before, and will be continued the next night, with an exemplary strictness. It's quite possible, as the saying goes. And since it has not been proved in the slightest that, in doing so, the "reality" with which I am kept busy continues to exist in the state of dream, that it does not sink back down into the immemorial, why should I not grant to dreams what I occasionally refuse reality, that is, this value of certainty in itself which, in its own time, is not open to my repudiation? Why should I not expect from the sign of the dream more than I expect from a degree of consciousness which is daily more acute? Can't the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life? Are these questions the same in one case as in the other and, in the dream, do these questions already exist? Is the dream any less restrictive or punitive than the rest? I am growing old and, more than that reality to which I believe I subject myself, it is perhaps the dream, the difference with which I treat the dream, which makes me grow old.

2) Let me come back again to the waking state. I have no choice but to consider it a phenomenon of interference. Not only does the mind display, in this state, a strange tendency to lose its bearings (as evidenced by the slips and mistakes the secrets of which are just beginning to be revealed to us), but, what is more, it does not appear that, when the mind is functioning normally, it really responds to anything but the suggestions which come to it from the depths of that dark night to which I commend it. However conditioned it may be, its balance is relative. It scarcely dares express itself and, if it does, it confines itself to verifying that such and such an idea, or such and such a woman, has made an impression on it. What impression it would be hard pressed to say, by which it reveals the degree of its subjectivity, and nothing more. This idea, this woman, disturb it, they tend to make it less severe. What they do is isolate the mind for a second from its solvent and spirit it to heaven, as the beautiful precipitate it can be, that it is. When all else fails, it then calls upon chance, a divinity even more obscure than the others to whom it ascribes all its aberrations. Who can say to me that the angle by which that idea which affects it is offered, that what it likes in the eye of that woman is not precisely what links it to its dream, binds it to those fundamental facts which, through its own fault, it has lost? And if things were different, what might it be capable of? I would like to provide it with the key to this corridor.

3) The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonizing question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart's content. And if you should die, are you not certain of reawaking among the dead? Let yourself be carried along, events will not tolerate your interference. You are nameless. The ease of everything is priceless.