note to dear reader :

HERE ENDETH THE PREFACE

MENIPPEAN TOPICS

The chief techniques of defining a work as Menippean satire have been three: either (a) simply by the formula, "a mixture of verse and prose," or (b) by a comparison of its contents with those of a known Menippean satire, or (c) by means of a "definitive" list of features. Each of these is inadequate to deal with the problem of definition of the form, Menippean satire. The first is inadequate both because it allows for the inclusion of works that are not Menippean, and because it excludes a great variety of works that are - that are either wholly in verse or wholly in prose. The second is inadequate because it too makes no provision for innovation. While the third (and most popular) likewise does not provide for innovation, it is also inadequate because critics have not agreed upon what such a list should contain and because, as this appendix illustrates, a complete and thereby definitive list would be unwieldy if it were in fact possible to compile one. Further, in all probability, no Menippean satire would use all of the ingredients of such a list. Moreover, all three techniques are inadequate because they result from appraising Menippean satire abstractly and descriptively, from a distance, and because they ignore the interaction of the satire with the reader.

As has been shown in Part One, descriptive or abstract approaches fail to come to grips with Menippean satire for the reason that it is inseparable from its effect on its audience. All of the features hitherto used to describe the form, or any example of it, may be regarded as tactics chosen by a Menippist to engage and retune the sensibilities of a reader by deliberately violating his sense of decorum in one or another way. If the catalog of features appears to grow with each period of Menippism, then, it does so because the Menippist has a new, or at least a different, audience sensibility to contend with. For each change of sensibility implies both an intensifying of awareness in some areas of experience and a blunting of awareness in others. Furthermore, the catalog may be enlarged for the Menippist by the development, either through his own work or others', of new literary patterns and techniques. This may in some measure account for the paradoxical fact that Menippean satire is at once highly experimental and highly conservative of tradition (it is mimetic).

The following list of Menippean topics does not attempt to be exhaustive: it includes little more than the commonplace features - e.g., those discussed by Frye, Williams, Bakhtin and Korkowski. While its size may demonstrate the futility of a merely descriptive approach, the list may serve another purpose. A structural study of these and other Menippean topics may eventually yield basic patterns of Menippean decorum which will in turn provide greater knowledge of how human perception is altered and managed.

TOPICS:

Almanackers. They were often used as the butts of the satires, as street-level philosophi gloriosi. Cf. The Owle's Almanacke by L.L. (Laurence Lyly). Astrologers have been attacked regularly by Menippists since Lucian's Astrologia. Cf. Nashe ("Adam Fouleweather"), Rabelais, Dekker.

Anonymous Author. The author's anonymity is apologised for in a fake introduction, for example, one written by the printer or bookseller who might plead any of several reasons. A common reason is that the author, a man of quality, does not wish to reveal himself as a writer of this sort of production. E.g.: Donne's Ignatius, His Conclave, Swift's Tale. In a variant, Joyce would often aver that his interlocutors in conversation, or passersby in the street, were composing and writing Finnegans Wake, not he.

Apologiae for the Work. One or more apologies are often used to establish relations to other Menippists, by citation, by reference, or by plagiarism. They can be used to establish tone, to banter with the reader, or to lay trails of red herrings. They may appear at the beginning of the work (as in Donne's Ignatius or in French editions of La Satyre Menippée) or anywhere inside as a digression (as in Harington's Ajax and Sterne's Tristram Shandy).

Autonomous Author. The author exults in a freedom to do whatever occurs to him. This topic is frequent. Examples include Lucian, Seneca, Fronto, Synesius, Erasmus (Folly), the Obscure Epistolers, Agrippa, Despérieres' dogs, Rabelais, Swift, Sterne, Byron. Sterne: "I have a strong propensity in me to begin this chapter very nonsensically, and I will not balk my fancy. - Accordingly I set off thus." (Tristram, p.74).

Autonomous Pen. The pen, or the act of writing, is remarked to take control of the author or narrative and to pursue its own course, observed and commented upon by the author who feigns powerlessness to control it. Ancient mock-eulogists had similarly feigned powerlessness to control their rambling oratory. E.g.: Epistolae Obscurorum Virorum (1516); Swift, Tale of a Tub; Sterne, Tristram; Nashe, Lenten Stuffe. Sterne has: "In a word, my pen takes its course... I write a careless kind of civil, nonsensical, good humoured Shandean book, which will do all your hearts good...." And: "But this is neither here nor there - why do I mention it? - ask my pen - it governs me – I govern not it." Tristram Shandy, ed., Work, pp.436, 416)Banquet. A favored Menippean device for displaying gluttony and other excesses, this topic also serves as both a strategy and a symbol of Menippean encyclopedism. The range of users is from Petronius (Trimalchio) through Rabelais to Finnegans Wake. (In the ballad, the party at the Wake becomes so rowdy that the corpse rises and joins in the fun.) The Wake is a banquet in many senses: of history, of learning, of languages, of personae, of words and puns, etc. Other examples may be found in Lucian, Convivium, the symposia of Varro, Athenaeus' Deipno-sophists, Macrobius, Beroalde's (Francois Beroalde de Verville's) Moyen de Parvenir (a philosophic banquet of the dead), La Satyre Menippée and Bouchet's Les Serées (1583-4). In the sixteenth century, the French seem to have enjoyed Menippean banquets particularly. Perhaps this topic is a direct link to the derivation of "satire" from satura lanx. See also Michael Coffey's article in the Oxford Classical Dictionary for a brief conspectus of ancient symposium literature.Blustering Narrator. The author asserts his authority (extreme), an assertion often couched in Herculean terms. This is often accompanied by a teasing of the reader and chitchat or feigned worry about the book's organization. Swift's is perhaps the most complete example. The hack, in Tale of a Tub, claims "Absolute Authority in Right, as the freshest Modern, which gives me a Despotic Power over all Authors before me..." and so on. This remark is contained in a "Panegyrical Preface," which is put in Section V of the Tale. The long line of Menippean precedents includes Lucian's Alexander the False Prophet, Cornelius Agrippa's De Incertitudine, Nashe's Lenten Stuffe, Burton's Anatomy (e.g., II.4.2.1, III.2.3, and I.2.4.7), and John Taylor. In A Voyage Round the World, Dunton demands, as he opens a new chapter, "Room for a Rambler - (or else I'll run over ye)."

Bookseller. The bookseller is used as an alternative persona by the (sometimes anonymous) author. In this guise, remarks can be made that bridge lacunas (q.v.) in the text, to provide prefaces or editorial marginalia or footnotes, or all of these. Swift's Tale is a representative example; others include John Taylor and Dunton ("Nimshag's" treatise on gingerbread). The anonymously-provided Catalog appended to C.G. Finney's The Circus of Dr. Lao is a more recent example.

Catalogs and Inventories. This digressive device shatters narrative and disrupts any attempt to establish single point of view or logical sequence. The arch-practitioners are Rabelais and Joyce. In the more learned writers, it is used as a device for moving the basis of the discussion from efficient to formal cause of an event or situation. It can also become a linguistic activity of the text itself, as with Joyce's thunders. Korkowski (p.242) cites Rabelais as the inventor of this topic and attributes its invention to the "new directions" in reading made possible by printing. This topic would seem to be another descendant of satura lanx, and to be writ large in other topics such as the banquet and encyclopedism. In its relation to the latter, it is often used to lampoon the cullings, anthologies and sham learning (reduced and systematized for efficiency) promoted by the gloriosi. The catalog technique is essentially grammatical. Catalogs can (and do) include anything - the contents of pockets, grocery lists, pawnshop receipts, ships' names, book titles (real or fake or both).

Descent into the Underworld or Afterlife. This topic is related to those of the tour through hell (or heaven), the fantastic journey, travel to the moon, Dialogs of the Dead and imaginary conversations (Cf. Landor). A fundamental Menippean strategy directly related to Cynicism, the descent is useful for exposing folly and pretension in this life by way of the "democratic" levelling and occasional comeuppances of the next. Swift's tour of the madhouse is a variety of the tour through hell: several of his "madmen" are doing, by their own inclination, exactly what the damned in other Menippean satires - particularly Dunton's Second Part of the New Quevedo - were doing as a punishment in the next world. This topic is especially used against the philosophi gloriosi, intellectual and social cranks, and snobs of all kinds. Menippus probably wrote one: certainly his two greatest ancient imitators did so - Varro and Lucian. Seneca's Claudius is of this type.

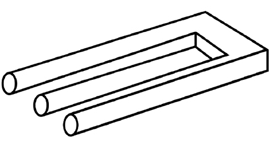

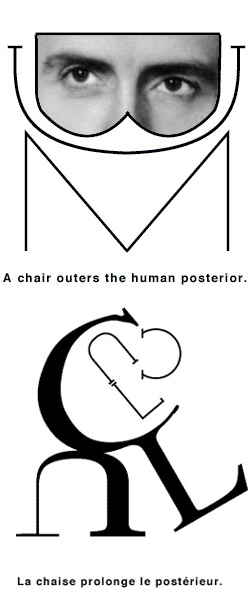

Diagrams and Drawings. The author reproduces in the text engineering plans for assembly of real or imagined machines, that may or may not be referred to in the text of the satire, and that may or may not work when assembled according to instructions (which may or may not be provided). This topic is often used to lampoon physicists, engineers and other "projectors" and schemers. In Harington's Ajax, to cite one example, none of the parts in the "disassembled" drawing can be found in the "assembled" drawing.

Dialogs of the Dead. A variant of the topics of Banquet and Descent into the Underworld, this device allows a cast of characters widely separated in time to be brought together. Their conversation, sometimes with the narrator, may run to matters concerning the audience for the satire, or each other, or trifles, or all of these.

Digressiveness. This has been called the heart and soul of Menippean satire. It is achieved in many ways. Nearly every Menippean topic is a form of digression from the normal or expected, ranging from violations of stylistic decorum to violations of narrative sequence, of time (Dialogs of the Dead), of probability (the author writes before birth or after death), of physical size or capacity (Rabelais), and so on. This can also take the form of repeatedly promising to come to the point, and never doing it, as in Harington, Dunton, Swift and Sterne, for example. The point of a passage in Finnegans Wake is seldom found except after extreme labors with the text, and then it may be an irrelevancy. For the Menippist, the labors are the point. In a variant, John Fowles provided several alternative endings to The French Lieutenant's Woman. Inherent in the structure of the frame tale (Milesian tale) and the double-plot epyllion, digressiveness is a strategy for attacking and adjusting the reader's sensibilities. It is a form of structural ambiguity.

Diogenes. He and other Cynic philosophers may be used in a satire as key characters, or may just be referred to now and then, or they can be used to provide running commentary from the sidelines on a satire. Rabelais gives his reader "licence" concerning his "pantagrueline Sentences" (a satire on Peter Lombard et al.) "to call them Diogenical." He parodies and greatly expands the account in Lucian's How to Write History of Diogenes' tub (Prologue to the Tiers Livre). The Tub, far more to Menippists than just clothing, reappears in Swift's Tale. A "tale of a tub" was, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an epithet for a kind of writing "suited to flimflam, idle discourse and a tale (sic) of a roasted horse" (A.C. Guthkelch and D.N. Smith, eds. of A Tale of a Tub). Equally, doggishness is invoked, as by Dunton:

"There stood Diogenes the Cynic, snarling at two Devils, that were going to Muzzle him, for he was so abominable Currish, he bit the Devils that came near him, His chief Clamour was... the Devils to quiet him, had promis'd to release him in Fifty years." (Second Part of the New Quevedo, p.78).Menippus also appears frequently in Menippean literature, e.g., in Lucian, or in Butler's "Hudibras in Prose," Mercuriis Menippeus. Burton's use of Democritus is proverbial. This topic is related to the establishment of the pedigree of a satire, as to Dialogs of the Dead and Digressiveness of time. It allows the Cynic spirit to be injected directly into the work.

Do it Yourself. The reader is told to add to, subtract from or rearrange the materials of the text to suit himself. In a muted form, the reader is advised to skip certain chapters or sections of the work as worthless or as potentially offensive (as Sterne, to his sensitive female reader). In another variation, the reader is told to refer immediately to other places in the text, which may be real or imaginary, apposite or not. An aspect of digressiveness, this device breaks narrative and continuity and helps to attract attention to the act of reading and to the text as an artefact. Thus it is related to the topics, lacuna-making and lacuna-pretending. Swift: "The necessity of the Digression will easily excuse the length; and I have chosen for it as proper a Place as I could readily find. If the judicious Reader can assign a fitter, I do here empower him to remove it into any other Corner he pleases. And I so return with great Alacrity to pursue a more important Concern." Sterne opens Vol. V, Chapter X by inviting the reader to fill in his own reasons for the pause in Trim's oration.

Doggishness. This topic includes dog-conversation, dog-philosophy, and other references to dogs. Directly related to the Greek pun on dog and Cynic, this topic serves to establish Menippean pedigree and to introduce the Cynic attitude and tone into a satire. Cf., Lucian, Rabelais, Byron, and others. "The fourth dialogue in the Cymbalum Mundi of Despérieres is a conversation between two dogs, Hylactor, or 'Barker,' and Pamphagus, or 'Devour-all,' who are well-versed in the anti-conventional sentiments of early Greek Cynicism; they look upon the human race with snarling disdain." (Korkowski, p.231)

Euphuism. Though not necessarily a Menippean topic, Euphuism yet has the potential to be one and exhibits a number of Menippean features including the display of learning, the use of incidental verses, and (sometimes) the dialog form. Euphuism was practised chiefly by John Lyly, William Painter, Thomas Lodge, Robert Greene and Nicholas Breton. Greene moved on to Menippism, with his Planetomachia and a series of "deathbed" productions. Whereas Menippean epistolary writings tend to come from the next world, Euphuistic "letters" are exchanged between romantic heroes and heroines, their friends, rivals, parents, and enemies. There is little mock or ridicule of learning in Euphuism.

Excess Baggage. Under this topic may be grouped all manner of illusions, pretensions, false learning or assumptions, etc., that are to be shed. This topic is a typically Cynic aspect of Menippism. Antisthenes, a student of Socrates and the man generally regarded as the first Cynic (in belief if not in outlandish behavior) replied, on being asked what learning was most necessary, "how to get rid of having anything to unlearn." Lucian's Charon observes, "... Hermes, you see what they [normal people] do and how ambitious they are, vying with each other for offices, honours, and possessions, all of which they must leave behind them and come down to us with but a single obol... Nothing that is in honour here is eternal, nor can a man take anything with him when he dies; nay, it is inevitable that he depart naked..." (Lucian, Vol. II, p.437)

Fake books. In some Menippean satires, these are promised to the reader (and never delivered). In variations, they are alluded to or cited as authorities, or whole libraries are invented (as Rabelais' Thélème). Mock erudition is one of the devices for satirizing academic or learned pretentiousness. Examples of this topic include: Harington's "tenth decad" of "the reverent Rabbles;" A Catalogue of Books of the Newest Fashion, "to be sold by Auction, at the Whigs Coffee-House, at the Sign of the Jackanapes, in Prating Alley" (included in The Harleian Miscellany, V.6); Thomas D'Urfey's An Essay Towards the Theory of the Intelligible World... (etc.); Burnet and Duckett's A Second Tale of a Tub: or, the History of Robert Powel the Puppet-Show-Man (they "refer the Dispute" - over whether the dead have sensation - "to my Eighteen Volumes in Folio coming out as a Comment upon Duns Scotus"); Johann Fischart's Catalogue Catalogorum perpetuo durabilis. Das ist: Ein Ewigwerende, Giordianischer, Pergamischer und Tirraninoschar Bibliotecken gleichwichtige und richtige Verzeichnuss und Registratur (1590), and countless others including the Obscure Epistolers, Erasmus, Swift, Sterne, Carlyle's Sartor Resartus and Finnegans Wake. Swift opens the Tale with a list of fake treatises, "which will be speedily published."

Fake Preface. Let this topic include all manner of fake prefatory and introductory material. The locus classicus for this topic is Swift's Tale: it presents the reader with a (digressive) dedicatory note "to the right Honourable John Lord Sommers" (by "the Bookseller," as the Tale was anonymous); a note from "the Bookseller to the Reader," citing Menippean relatives; "the Epistle Dedicatory, to His Royal Highness Prince Posterity" using the Senecan/Lucianic claim of truth; "the Preface," lengthy and digressive; and "Sect. 1 - the Introduction," lengthy, digressive, and replete with (fake) lacunae, citations and descriptions of fake texts. Sterne places a (digressive) dedication at the end of Vol. I, ch. VIII, and uses the next chapter to comment upon and slightly emend it: "... the rest I dedicate to the MOON, who... has most power to set my book a-going, and make the world run mad after it..." His "the Author's Preface" appears in Vol. III, ch. XX. See also D'Urfey's Essay: the section "Of Prefaces" is not a preface; near the end of the book a pointing hand indicates the centred message, "HERE ENDETH THE PREFACE."

Fake Table of Contents. This topic is of a piece with the preceding one and includes misplaced Tables of Contents (as in Du Cliche´ á l'Archetype: la Foire du Sens, where the chapters are in alphabetic order, and the Table under T). Principally, however, this topic refers to a Table of Contents that lies, that promises matter and chapters not in the book. D'Urfey sets out a prefatory table of contents for his Essay, announcing "sections" never to be found, or given in vastly different form.

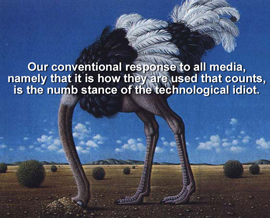

Forcing the Reader to Think. This is basic to all Menippean strategy and derives from the Cynic demand to "wake up!" A sure means of accomplishing this is by challenging the reader's assumptions and by violating his expectations about narrative continuity, truthfulness, decorum of style, and literary conventions (e.g., that diagrams refer to textual matter, or that promises will be fulfilled). One means is Joco-Seriousness (q.v.), the expenditure of lavish erudition on trifles and vice-versa. Another means is using paradox (including paradoxical encomia) to involve and intrigue the reader, for intellectual detachment and reflection.

Gibberish. Properly one of the language topics, this includes nonsense words, phrases, sentences or paragraphs. The result can be hilarious. E.g., the scholarly labor thus far expended in attempts to decipher the "languages" in Gulliver's Travels are a Menippean "side effect" of that satire whereby the scholars' efforts and reports become an additional "chapter," in which they satirize themselves unwittingly and unmercifully (because they're not playing). Users range from Rabelais' "Corrective conundrums" (Gargantua, 2: gibberish punctuated by gaps), to Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky, to Finnegans Wake, which some critics argue is entirely gibberish, "a monstrous joke."

Glosses. This topic embraces fake glosses, false erudition, irrelevant glosses, and includes similar play with footnotes and other marginalia and "editorial" digression from the text. Examples: Lyly, The Owle's Almanacke (mock-serious marginalia), Swift, Dunton. Sterne used a variation by putting his characters into tableaux (his "Shandean way of writing") for sentences, paragraphs or even chapters at a time, so he could mount digressive hobby-horses. Joyce used it all in the "Triv and Quad" chapter of the Wake. Often fake and real are interspersed, leaving matters to the reader to sort out. Swift glossed the Tale with one of the Tale's critics' remarks. This topic is clearly related to Digressiveness.

Groping. There are several forms: one is for the "mot juste." Alternatively, the author either pretends to have lost his way, perhaps due to digressions, and to be unable to find it again (often in Sterne); or he pretends to reach for the ineffable and to lose it, while remarking to the reader that in any case no direct understanding is possible. Korkowski points out (p.281) that Beroalde goes a stage further in noting that his own work, which admits only of being a "moyen de parvenir" and not an actual arrival, "is more honest than other books which offer definitive statement but no comment on the lack of ontological certainty in reading and language":

"Sur quoy je vous diraiy un grand secret, et puis l'autre; c'est que vous ne trouverez point en cecy du truandage de pedantisme, comme des autres, pleins du ravaudage de folle doctrine qui n'aporte pointe á disner. Et davantage, je vous diray le secret des secrets; mais je vous prie, afin qu'il soit secret, de vous embeguiner Ie museau du cadenac de taciturnité, et ecoutez: CE LIVRE EST LE CENTRE DE TOUS LES LIVRES. (Le Moyen de Parvenir, p.32)

Honesty. "I promise you purest truth," followed by whopping lies. A basic and frequent topic, this includes all the varieties of misrepresentation, misleading and fakery. Lucian's True Story is the touchstone.

How to Read the Book. The reader is given clues or instructions by the author. A feature of most Menippean satires. E.g., Sterne Vol. I, ch 13 (instructions promised), Rabelais, Byron, Joyce.

Inability to Edit Anything Out (feigned, of course). This is related to such other topics as Catalogs and Encyclopedism. Examples: Harington, Sterne, Nashe, Swift.

Joco-seriousness--see Spoudogeloion.

Kidding or Teasing of a Female Reader. Digressive chitchat with female readers (of delicate sensibilities), which may include lines that the writer supposes will come from the reader. This topic is best exemplified in Beroalde and Sterne. Cf. Tristram Shandy I.vi; I.xviii, and passim, to "Sir," "your Lordships," "Madam," or "Dear Jenny." Cf. especially the thinly-veiled hints of sexual horseplay he gives her, at p.226, facing the Marbled page (Word, ed.). Beroalde litters the Moyen with such asides, as does Bouchet. Dunton does the same.

Lacunae. Cf. Digression. The fake lacuna, a form of caprice with narrative continuity and order, is used commonly by Menippeans to tease the reader (Cf. Beroalde, Swift, Sterne). Sterne is the handiest English paradigm. He used blank pages, black pages, marbled pages ("motley emblem of my work," III.xxxvi), and omitted chapters.

Carlyle used a new variation: he told the reader that the materials for the 'Autobiography with "fullest insight"' of Teufelsdrókh arrived in the editor's hands in six "considerable PAPER-BAGS, carefully sealed, and marked... with the symbols of the Six southern Zodiacal signs." These contained a hopeless jumble of assorted Sheets, Shreds and Snips on every imaginable trivial and inconsequential subject. (Sartor Resartus, ch.XI) D'Urfey is replete with chasms, even to a section titled "the Method of Making a Chasm or Hiatus, judiciously; the great Reach of thought requir'd for the Contrivance thereof, together with the Difference between the French Academies and the English."

Language. A variety of topics appear under this heading, which designates matters pertaining to the language found in Menippean satires.

Bad Language. Mis-users of language are often a target of Menippean satires: this is an aspect of the Menippists' relation to grammar and its concerns. Korkowski: "One particular fraternity pretending to learning that has incurred Menippean censure, regardless of periods, is the mis-users of language: the rigid grammarian, the sophist who deals in glittering speech, the hack poet, the fanciful etymologist, the word-torturer, and the 'systematizer' of language are the genuine bétes-noires of the Menippist... on the theme of correct language and in degree of linguistic brilliance, Menippism as a species of controversy has no equal in quality. Bonaventure Despérieres' Cymbalum Mundi, Beroalde de Verville's Moyen de Parvenir and Swift's Tale of a Tub are to the problems of words what the very greatest thinkers' works have been to problems of philosophy." (pp.61-62) Cf. Pope's Peri Bathous (part of the "Martinus Scriblerus" project that produced other, independent Menippean productions, e.g., Gulliver's Travels). Finnegans Wake uses every rhetorical and grammatical device known, and every resource of the language-as-storehouse-of-experience. Joyce noted that he had to "put the language to sleep" to obtain the necessary freedom. The linguistic hi-jinx of the Wake are not without precedent, however. Rabelais used the Menippean form of language-tinkering. Apuleius, Martianus Capella and Alan of Lille wrote the most playful (to a Menippean; "tortured" to the sober critic) Latin extant. Following Rabelais, Etienne Taburot published his Les Bigarrures, a playful and exhaustive tampering with the humorous possibilities of disrupting the ordinary conventions of logical structure, sentence structure, word ordering and even letter orders; puns, obscenities, parodies of printed symbols, and relentless para-logical hoppings from one word to some strange equivalent or associated term, occur. His displays, however, tend to be little more than catalogs, set out one after the other, of ingenious lingual transpositions. (Korkowski, p.267)

Deluding Word. Words' numinosity is related to the topic of their correct usage and is persistent in Menippean satire. (All of the language topics - chief Menippean concerns - show the direct relation of these satirists to grammar.) Cf. the Obscure Epistolers, Martianus Capella (the aptness of the marriage of Mercury and Philology - rhetoric and grammar), Alan of Lille's De Planctu.

Fake Etymologies. This kind of grammatical horseplay by Menippists satirizes the sober ineptitude, clumsiness or superficial learning of the dialectician who tries to take over grammar with logic and philosophy. Equally, it is used to lampoon the inept or unlearned grammarian. Mostly in use since the nominalist/realist debate, it is related to the definition or the absolute meaning, or the absolute nature of things. Cf., Beroalde, Despérieres, Rabelais, Sanford's Mirror of Madness, Swift (e.g., "Antiquity of the English Tongue"). Its use is frequently accompanied by a display of erudition (real or fake, or both) of authorities in support of or contending about the etymologies. "The abnihilization of the etym" (FW 353.22). Related to Nothing.

Gibberish as language (see above).

Letters of the alphabet, as things, as praised, blamed, at peace or at war with each other, etc. This topic occurs often, from Lucian (The Consonants at Law) to Joyce (FW 119-123). Punctuation is also a topic, similarly handled (FW 124, for example), as are parts of speech. Cf. Guarnas' Bellum Grammaticale, Sterne on verbs (copular; copulation) and "auxiliaries," Alan of Lille.

Mixed Languages. This topic refers to the use of more than one language in a text, perhaps without adequate (or any) justification. A form of digressiveness, it can be related to tactics of violating decorum, as each language embodies the perceptions and experiences of the user culture, and it can include fake language (as in Gulliver's Travels). Among others, Varro and Burton display polyglottism. Sterne provides Slawkenbergii Fabella at the outset of Vol. IV (Tristram Shandy), accompanied by a simultaneous translation on the facing pages that is six times as long as the Latin. Joyce inserted sections in Latin and in French into Finnegans Wake, in "Finneganese," and his puns and thunders use fifty or more languages.

Prose-Verse Mixture was used in antiquity as the hallmark of Menippean satire and is still adhered to as a sine qua non by many classicists and critics. A digressive technique related structurally to both etymologies of satire, the mixing of verse with prose constituted a violation of decorum calculated to shock the sensibilities of the percipient reader or hearer into alertness. It is often combined with Joco-Seriousness (and related topics) as high style is employed on base matters, and vice-versa. A variation was the sprinkling, through a prose text or dialog, of lines and verses misappropriated (and misapplied, used on quite different subjects) from ancient or epic poets. Cf. Lucian's Charon.

Words as Gestures, and vice-versa. Words and language are used on a supra-semantic level where they shed their "contents" of usual meanings and function as eloquent acts. This topic is an aspect of all Menippean language-tinkering: the prime example is Joyce's thunders. For the reverse, gestures as words, see Rabelais, Gargantua 2; Pantagrual 19. In either variation it is a form of digression from normal accidence and syntax.

Words as Things, and vice-versa. The preceding topic draws attention to eloquence inherent in the formal character of utterance: this topic deals with the relation between language and artefacts. Both topics are grammatical and formal; though serious, this device is most often used ludicrously. Cf. Swift, Gulliver's Travels, Tale of a Tub. Things-as-words (or events) stand in direct relation to the Medieval grammarian's techniques of exegesis of the Liber Natura, a parallel text to the Liber Scriptura, echoes of which survive and persist in the poets. Cf. Don Juan, III.88 (note the Menippean-Cynic tone):

"But words are things, and a small drop of ink, Falling like dew, upon a thought, produces That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think; T'is strange, the shortest letter which man uses Instead of speech, may form a lasting link Of ages; to what straits old Time reduces Frail men, when paper - even a rag like this, Survives himself, his tomb, and all that's his."The written or printed word is a thing, inarticulate in itself.

Laughter. Laughter may be Democritean (e.g., Lucian and Burton), Diogenical (e.g., Rabelais), Wakean ("Lots of fun at Finnegans Wake") or routinely Cynic-Menippean. Both a topic and a tactic, laughter is indispensable to Cynic joco-seriousness, to retuning the reader's sensibilities by means of an engendered playfulness, and to curing him of undue or misplaced sobriety. In this regard it is related to topics of Digressiveness and of violations of decorum. Bakhtin has this as the quintessence of carnivalism, which he identifies with Menippism. Burton resounds with Democritus' laughter. Cynic laughter and wit runs through Beroalde, who notes in his first chapter that he directs laughter at the philosophers "because mirth must be restored." There's "lots of fun at Finnegans wake."

Learning. Cf. Encyclopedism, Fake Books. Respect for maintenance of the traditions (grammatical) of genuine learning and encyclopedic wisdom is concealed under attacks on all forms of easy, simplified or systematized "learnedness," pseudo-intellectual and philosophical extremism and universalising. Examples: Menippus, Varro, Petronius, Seneca, Lucian, Erasmus, Rabelais, Swift, Flaubert, Joyce. The Scriblerians (Pope, Arbuthnot, Swift, Gay) aimed to produce periodically a Works of the Unlearned: Flaubert got somewhat farther with the project with Bouvard. Cf. Sterne on noses (gnosis).

Medicinal. This topic is related both to the sanative powers of satire in general, and to those of Menippean satire in particular. Menippean authors frequently refer to their satires as having curative properties. This can range from generalities, such as "Written for the Universal Improvement of Mankind" (Swift, title page of the Tale, spoofing the gloriosi), to more pointed claims that the work is a "medicine," as in Rabelais, or in Burton, or Dekker:

"… more potent, and more precious, than was ever that mingle-mangle of drugs which Mithridates boyld together. Feare not to tast it... the Receipt hath beene subscribed unto, by all those that have to do with Simples, with this moth-eaten motto: Probatum est: your Diacatholicon aureum... pledge me, spare not... take a deep draught of our homely counsel." - Dekker, The Guls Horne-Booke (Non-Dramatic Works, Vol. II, pp.213-214)Memory of Time before Birth. The author discusses (as a spectator) events that occurred before his birth. Sterne (Tristram Shandy is not born until well into the third book) presents a mass of irrelevant detail on the events that preceded and surrounded both his narrator's conception and his birth. Dunton rambles through memoirs of his earliest years, including the years before he was born: chapter one of Vol. I treats "Of my Rambles before I came into my Mother's Belly, and while I was there." His rambling narrator, Kainophilus, adds a twist to the theme, complaining that he made no notes on the moment of his birth (though he made, somehow, plenty of notes in utero) as he was born without anything to write with - in fact, "Because I was dead born, I can't remember anything on it to save my life."

Method. Dialectical systematizing and universalizing is a common butt of Menippists, and as such continues the grammarians' attacks in the battle of Ancient vs. Modern. Cf. the Cynic disdain for all forms of easy or systematic (abstract) answers to any of life's problems, which result in the individual not thinking for himself. E.g., Swift spoofs the gloriosus lightly in presenting the Tale "for the Universal Improvement of Mankind," and savagely in the stupidity of his hack. Sterne lightly but thoroughly dissects Locke, Carlyle the German gloriosi. The structure of Burton's Anatomy parodies post-Ramist branched-logic systems. Cf. Moderns.

Mock Eulogy. Taken directly from epideictic rhetoric and the topics of laus et vituperatio, the paradoxical encomium goes back at least as far as Gorgias' Praise of Helen. Just at what point this enters Menippean lists is hard to say. One of Varro's Menippean satires has the title, "Two asses will praise each other" - Mutuum muli scabunt. Lucian wrote many mock-eulogies, e.g., Phalaris I and II, Peregrinus, Alexander, Saltatio and Muscae Laudatio. Cf. also Erasmus' Praise of Folly, Panurge's "Praise of Debtors" (in Le Tiers Livre, ch. 22), the "harangues" of La Satyre Menippée (1594), Burton's Anatomy (III.2.l.l), Swift's praise of Madness in the Tale, Nashe's praise of the red herring in Lenten Stuffe. Further examples in Rabelais and others are discussed in Colie, Paradoxia Epidemica. Sterne is careful always to praise Locke while he demolishes his theories. Korkowski notes that "after Lucian (and even before him) the satirical eulogy is identified with this Menippean tradition by knowledgeable authors. To men of the Renaissance, for example, Lucian's mock-praises appeared germane to snarling Cynicism; almost anything by Lucian, for that matter, was regarded as proceeding from a common Menippus-Lucian temperament... That the mock-encomium and 'other' Menippean forms were perceived as identities can be gathered from Erasmus' epistle to Thomas More, introducing the Praise of Folly..." (p.98)

Moderns. The "moderns," or dialecticians (gloriosi) in all ages, are a target of Menippists. The line of attack runs through Menippus, Varro, Petronius, Lucian (e.g., The Sale of Philosophers), Erasmus, Cervantes, Rabelais, Voltaire, Butler, Dekker, Nashe, Swift, Sterne, Carlyle, Flaubert and Joyce. Cf. Method.

Musical Notation. The verses interspersed with the prose frequently have the potential of being used independently as songs. However, this topic refers particularly to an interruption of the running text by offering the reader the notes and musical notation of songs, with or without the verses, and which may or may not be musical or euphonious. Examples include Bishop Francis Godwin's (1638) The Man in the Moon (the moon-giants discourse in a wordless language of music made up of standardized tunes, several pages of which are presented to the reader as a message of moment to Englanders) and Cyrano de Bergerac's Histoire Comique des Etats et Empires de la Lune et du Soleil (his moon-people are like Godwin's: they speak a language of tunes that appears in the text as musical notation). Korkowski notes (p.330), "this was not new in Menippean satire" and refers the reader to the Sermo Quodlibeticus de Podagrae Laudibus in Dornavius, and Taburot's Bigarrures for precedents. Harington includes pages of music in Ajax. Joyce includes the written melody for "The Ballad of Persse O'Reilly" in Finnegans Wake (pp.44-47), and two other written melodies in the "Ithaca" chapter of Ulysses.

Mutilated Text. The author, either as himself or in the person of a publisher or editor or critic, presents or comments upon a text that he claims is corrupted, mutilated or otherwise interrupted by lacunae. See Lacunae.

Natural Scale. Inseparable from the other Cynic topics, this one refers to Cynic insistence on not exceeding the limits of human scale, which includes constant attention to our human frailties, limitations, susceptibilities to pride, self-aggrandizement, and so on. In Menippean satire, this is an aspect of the Cynic wind that blows through the satire as much as it is an aspect of the purposes of the satire. The reader's sensibilities are to be so revivified that he becomes aware of his deviation from, and will develop a preference for restoring, human or natural scale in his activities, psychic and social.

Non-sequitur. Deliberately used by Menippists, the non-sequitur is related to lacuna-making, digressiveness and all forms of interruption of narrative sequence, q.q.v. Non-sequiturs are the order of Beroalde's book. To make his reader aware that "straight-line" narration is a purely arbitrary order, Sterne, sending up Locke, denies his reader what is expected, interrupts the continuity of narrative logic at every turn, displays the pieces, and then asks innocently what they are and how they should go back together. In Ulysses, Joyce found new variation on this topic in the technique of "simultaneous parallels" with Homer, as well as in the discontinuities of "stream of consciousness."

Nothing. This topic, a frequent subject in Menippean satires, includes writing on recondite trivialities ("nothings"), often with a display of immense erudition, or, literally, writing whole chapters on "nothing." This latter is related to satirizing gloriosi logic-choppers who cut matters so fine that their weighty systems are brought to bear on "nothings." Dunton's Voyage offers "admirable and surprizing Novelty of both Matter and Method; a Book made, as it were, out of nothing, and yet containing every thing..." Ulysses and Finnegans Wake may equally be said to be made of "nothings" and yet to "contain everything." Cf. also Nashe, Sterne. Most Menippeans try their hand at this topic at one time or another as sustaining it calls for high wit and inventiveness. Swift: "I am now trying an experiment very frequent among modern authors; which is, to write upon nothing; when the subject is utterly exhausted, to let the pen still move on; by some called the ghost of wit, delighting to walk after the death of its body..." (etc., from the "Conclusion" to the Tale). Rabelais lavishes formidable amounts of attention upon bagatelles (as does Macrobius on the egg, and Athenaeus on odd kinds of fish). Panurge's decision to marry, for another example, becomes the focus of an enormously prolonged, prolix and pettifoggish debate leading to nothing.

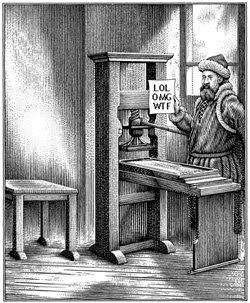

Parody of New Forms. The chameleon-like and mimetic nature of Menippean satire, which contributes to the impossibility of accounting for it descriptively, gives it immense flexibility and adaptability to new forms and new situations. As soon as new genres or modes or media for expression appear, Menippists quickly adapt to the new form and begin to explore its satirical possibilities. This was done, for example, by Rabelais, Nashe, Dekker and Aretino, as Korkowski points out (p.225). Rabelais puts on the pretensions of the new "learned" genres made popular by printing. Somewhat later, Swift creates hiatuses with a new symbol, the asterisk, and Sterne toys with all the devices of the book, even to turning it inside out by putting the marbled end-papers in the middle. Flaubert aped the popular press in declaring his ideal novel would be all style and no content. Joyce used cinematic technique in Ulysses and remarked that the Wake was written "after the style of television." The study of Menippism in modern media has not yet begun. I suggest that there is no reason why it should not have expanded beyond the confines of written or printed texts once audiences were formed by and could be hypnotized by other-than-literate media. One might begin such a study with Orson Welles (Radio), Woody Allen (Film), and Steve Allen or Norman Lear (Television). The mind boggles at what havoc a determined (Cynic) Menippean might wreak with the telephone, or computer data-bases and systems analysis, or satellites. We may yet find out. See Printing.

Philosophus Gloriosus. He is the favorite Menippean whipping-boy. Philosophers (dialecticians) are open to Menippean attack on several grounds. First, their whole enterprise is traditionally based upon abstraction of ideas and reasoning, which the Menippist can castigate as a form of undue exaggeration and equally as a retreat from reality. Second, their reliance on logic as a tool and the fine distinctions and rare abstraction into which that often leads also fuels the Menippean fire. The grammatical side of Menippean satire would have at the gloriosi in any case, as a skirmish in the quarrel of Ancient with Modern. Those are general terms: particular targets are more usually members of fashionable and pseudo-intellectual groups, as in Seneca's Apocolocyntosis (the ignoramus Claudius and his retinue of hack poets) or Petronius' Satyricon, or in Erasmus or Lucian, in Hudibras, or Tristram Shandy. Swift sent up one group in the Tale, quite another (the equivalent of the mad scientist) in Gulliver. Carlyle takes aim at the invasion of German philosophy in Sartor Resartus (tailors are second only to philosophers as Menippean targets), and Wyndham Lewis at Bloomsbury pretentiousness in his Apes of God. The pseudo-learned of all sorts are the favorite quarry: these fakes - the real gloriosi - have usurped the place of the genuinely learned, have bamboozled the less educated, and have used the appearance of learning and wisdom for worldly gain. They are as thieves and polluters. In our time, the bestseller writer is as much a gloriosus as was Locke in Sterne's.

Printing Conventions Trifled With. Cf. Parody, above. This topic concerns horseplay with the conventions of printed books. Practitioners include Rabelais, Nashe, Harington, Sterne, Joyce. In a variant, Rabelais (as Swift, etc.) claimed that his text had been botched by incompetent printers (a common enough complaint even now by authors): "For the benefit of the warriors I am about to rebroach my cask, the contents of which you would sufficiently have appreciated from my two earlier volumes if they had not been adulterated and spoiled by dishonest printers..."

Projectors as targets. This refers principally to the mad scientists and crazed philosophers of Swift's time (Cf. Philosophus Gloriosus): they seem to be accounted as of the same family as astrologers, alchemists, etc. Swift's "Grand Academy of Lagado" has an ancestor in Joseph Hall's Mundus alter et idem, an account of travels to and the fabulous goings-on at "Terra Australia Incognitis." The most populous region of Australia, Fooliana, has a university, called "whether-for-a-pennia," where specimen sciences are taught, including penny astrology. In one college, "Gewgawiasters" are busy inventing a way to blow soap bubbles from walnut shells: they have also invented projects and novelties in "games, buildings, garments and governments," and have devised a new language, the "Supermonicall tongue."

Reader. He is the real target of Cynic Menippism. The reader is kidded, cajoled, threatened, flattered, etc. by turns, and if the satire is successful he will enter into or put on the spirit of the work. Frequently, the author himself (or wearing one or another narrator's persona) will engage in lively discourse with the reader on any topic that comes to mind, including the right arrangement of the book, the reader's habits or his dress, etc. Like Swift before him, and Sterne after, D'Urfey's Gabriel John empowers his reader to transpose things to his own liking (in the section "Which end of a Book to begin at"). As Finnegans Wake is written in a circle, the reader can begin anywhere. Joyce expected his reader to abandon all other pursuits and devote full time to studying the Wake. Rabelais makes the same demand:

"I intend every reader to lay aside his business, to abandon his trade, to relinquish his profession, and to concentrate wholly upon my work. Rapt and absorbed, all might then learn these tales by heart, so that if ever the art of printing perished and books failed, these tales might be handed down, like mystic religious lore, through our children to posterity! Is there not greater profit in them than a rabble of critics would have you believe?" (Prologue to the Second Book)Evidently, Menippists, like the Cynics, regard "staying awake" as a full-time business.

Simultaneity of Past and Present. The cast of characters in a Menippean satire will often include persons widely separated by chronological time. Linear, chronological time may be circumvented by a device such as setting the scene in the afterworld (Dialogs of the Dead, etc.) or may simply be ignored altogether as in Beroalde's Moyen de Parvenir, in some of Landor's Imaginary Conversations, in Pound's Cantos, and in Finnegans Wake, to mention but four. This same attitude to the irrelevancy of mere chronology was present in the translatio studii of the grammarians, and marks another affinity between their enterprise and the Menippean one. As already pointed out, this topic is also implicit in the mimetic nature of Menippean satire. In our time it has received explicit statement in T.S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual Talent," and has been used extensively in his poetry, notably in "The Waste Land" and in Four Quartets.

Spoudogeloion. Cf. Joco-seriousness.

Tailors. Tailors are common as the butts of Menippean satires; in some periods they are second only to philosophers as objects of attention. Carlyle mounts a combined attack in Sartor Resartus. Tailors receive attention via Cynic attacks on pomposity and pretentiousness, for covering up bodily defects or for taking attention away from real matters to waste it on illusory corporal beauty - a kind of seduction. Diogenes wore his tub; Dunton has his Parable of the Top-Knots; Swift his Shoulder-Knots. Satires on tailors are to be found in L'Estrange's Quevedo and in Greene's and Dekker's treatments of tailors in Hell. (Dekker weighed the old world's tailors and the new together in The Guls Horne-Booke.) In the Wake, Joyce explores the seduction-via-clothing theme with his Prankquean, and riots with the story of Kersse the tailor trying to fit a suit to a hunch-backed Norwegian ship's captain.

Talking Animal. Korkowski notes (p.170, n.49) that "the talking animal, in ancient literature, hardly appears outside of Menippean writings (i.e., Lucian's Gallus, Apuleius' ass, Plutarch's Gryllus)." In Menippean satires, anything and everything, including animals, and even words or letters, may give voice. In the Circe chapter of Ulysses, speeches are delivered by a gong, a bar of soap, wreaths, gulls (birds, not fools), a timepiece, the quoits of a brass bed, bells, chimes, a crab, a hollybush, bronze buckles, a cap, a gramophone, a gas-jet, a doorhandle, a fan, a hoof, the sins of the past, Sleepy Hollow, Yews, a waterfall, halcyon days, a mummy, characters' voices, Orange Lodges, a pianola, bracelets, "the hue and cry," the voices of "all the damned" and "all the blessed," and a horse.

Tradition. Tradition may be singled out as object of attack: the Menippist impersonates an enemy of (grammatical) tradition, of the Ancients, and bungles the job. Cf. Dekker (The Guls Horne-Booke) and Swift in his "Digression in praise of Digressions."

Universalizing. Glib universalizing appears as the butt of many satires. Cf. Philosophus Gloriosus above. Practitioners include Cynics, Lucian, Rabelais, Swift, Von Hutten, Erasmus, Flaubert.

Universal Schemes (treated variously, above). This refers to Menippean mockery of dialectical or scientific universalizing by projecting crazy schemes of their own, as in Sanford's Mirrour of Madnes, Swift's Modest Proposal or his "Digression concerning the original, the use and improvement of madness..." (which derives from Sanford). Such schemes are proposed, as are many of the satires, "for the universal improvement of mankind." Rabelais and Cervantes are thoroughgoing and merciless, as is Flaubert.

Whatever enters my head. An aspect of the autonomous author, this topic is related to pretended inability to manage a discourse. Seneca has: "dicam quod mihi in buccam venerit." A host of others followed suit, including Burton, D'Urfey, Sterne and the writers of Finnegans Wake (the public, the users of the language whom Joyce patiently studied).

note to dear reader : THIS IS NOT WHERE THE PREFACE ENDETH

-----------

THE NEW YORK WITS

- Herbert Marshall McLuhan, KENYON REVIEW, Vol. 7, #1, 1945, pp.12-28

It may indeed turn out that the present cleavage between popular and rational forms of entertainment will never be mended. The common reader with whom Dr. Johnson rejoiced to concur is as dead as Pan. And just how many centuries of intellectual ascesis concurred with centuries of homogeneous social life to produce him, we are now privileged to contemplate. As late as Crabbe and Jane Austen serious art could hold the same road as “good society,” following the main march of the affections. Even putting aside Blake and Wordsworth, one could say that after Jane Austen no serious artist exists save in drastic opposition to his society. The practical reason of the artist involuntarily has come to indict the life around him as a sensual riot willfully opposed to reason and order.

Even successful writers like Dickens and Thackeray preserved their line of popular communication with the taste of their time at the expense of their art. Their refusal to confront their experience critically meant that they never raised the material they worked with to the level of art. Pickwick and Scrooge, Uriah Heep and the brothers Cheeryble announce but do not explore the Jekyll and Hyde schizophrenia which deepened not in Dickens’ art but his own unconscious right up to the last page of Edwin Drood. Even the most lively and satisfactory of Dickens’ characters offer more material for the psychoanalyst than for the critic. Dickens was thus largely an unconscious and not an artistic mirror of the lower middle-class conflicts of his age. Thackeray was related as middle-brow reading in his own day – a furrow or two above Dickens. Basically he offers us only one character and one pose – that of a mellowed and PETIT regency rake contemplating through a mist of senile tears the innocence of childhood, the fragrance of young womanhood, and the sordid fate that awaits them both. A mildly cynical nostalgia is his sole stock-in-trade. Of course his middle-aged narrators were, as young lads, middle-class imitators of the Byronic frenzy, as he was. In later life they gaze back upon the years from the windows of their club and waggle their heads at the fact that boys will always be boys. Nobody in Thackeray ever passes beyond adolescence.

Neither Tennyson nor Browning was equipped to grapple with a fraction of the life which he pretended to focus in his art. Both were vulgarizers of easily discovered attitudes to experience. At a higher level, admittedly, one encounters in them the same clinical material found in Dickens and Thackeray. The esthetic lyricism of Tennyson – the only side of him which, apart from ULYSSES, asks to be considered critically – as it occurs, for example, in THE PALACE OF ART, turns a frankly hostile and uncomprehending glare on everything save the dreams and images which compensate a sensitive young man for the theft of his intellectual and social inheritance. He pursues the past which Keats contemplated but rejected in his ODES. On the other hand, the sense in which the patriotic and public Tennyson embraces life is akin to Henley and Kipling for whom it prepared the way. It is pathological in its “pseudo” quality, its capacity for inversion and reversal. As for Tennyson’s ruminations about science and the social developments of his time, they convince us merely that he was disturbed. Arnold’s superior intelligence in such matters comes off little better in his poetry. Browning makes an omnivorous rush at life (“grow old along with me”), but the characteristic conflicts which occur in such representative poems as “Porphyria’s Lover” and “The Last Ride Together” are extraordinarily adolescent and banal. (Superficially diverse, the attitudes of the disappointed lovers in these poems is radically the same. In both instances, an adolescent over-valuation of romantic sentiment is an occasion for sadistic and masochistic heroics of a sort which afterwards became cliché.) Browning succeeded in getting the accents of human speech back into poetry in a way which perhaps prepared the vogue of Donne and which can be found fruitfully present in the early Pound and Eliot. However, his DRAMATIS PERSONAE strike the merely conventional poses of his age and the result is utter slackness. For example, the Duke in “My Last Duchess” is about as interesting as George Sanders would be in the stereotyped role of a proud heartless aristocrat heavily lacquered with the manners of Renaissance culture. He is merely the villain of Victorian melodrama, another glamorous Lovelace or French aristocrat of English middle-class fancy (a guilt fantasy) who survives as Hollywood’s Basil Rathbone. In Browning, too, then, the material of his art is never raised to that point of artistic awareness and intensity where the sensible matter and the intelligible form are one. Much of his appeal still depends on the persistence in the Anglo-Saxon world of just those emotional attitudes which he reflected but never grasped or interpreted.

Such is still the price of being a “representative” artist, a writer acknowledged by weekly reviewers as being of major dimensions. What, meantime, of the oppositional and “revolutionary” art of a Blake, Wordsworth, Rossetti or Swinburne? The last two names would serve to put us on our guard. Whereas in France revolutionary feeling was supported, in the case of the symbolists, by an impressive intellectual effort, the English equivalent was not. A Mill, a Carlyle, a Ruskin, or a Spencer solemnly functions at an intellectual level as remote from the significant experience of the age as a TIMES editorial. In England, therefore, “feeling” is frankly escapist and “thought” is concerned with the alarming condition of the working classes.

Revolutionary politics in Victorian poets are no more surety for artistic quality than a show of VERS LIBRE was the day before yesterday. Insofar as the Pre- Raphaelites linked a dandified bohemianism with an unconventional aesthetic doctrine (like Shelley in this), they tried but failed to combine the aristocratic contempt for commercial society, which has its type in Byron, and the artistic sense of relevance such as one finds in the Preface of LYRICAL BALADS or the BIOGRAPHIA LITERARIA. But Wordsworth and Coleridge, for all their youthful enthusiasm, were basically middle-class and rediscovered their basic loyalties later in life. Byron, on the other hand, (and Scott, too, in his way) was a conventional artist expressing a widely felt “aristocratic” revulsion for the sordid term which commerce had given to the national temper – the same revulsion that was expressed by Burke and Cobbett.

For the purpose of “placing” the New York Wits it should be noted that the Byronic strain of alienation has important antecedents in the 18th Century and interesting derivatives in the 19th and 20th. In the 18th Century it can be traced in the emotional conflicts of both CLARISSA HARLOWE and TOM JONES, in Sterne as well as Mrs. Radcliffe. After Byron it is found in Swinburne and Wilde, in Poe, Stevenson, and, more popularly, in detective fiction with its dandified and socially alienated sleuths. No acumen is needed to see how Lord Byron is understudied by Dupin, Sherlock Holmes, and Lord Peter Wimsey. Nothing more lushly sentimental or feebly Satanic than modern detective fiction could be imagined. And it is significant that its pathology is such that no serious artist could conceivably manipulate its outmoded emotional attitudes any more than serious art could be managed on the basis of the related matter of Victorian melodrama.

It will be seen that some such perspective as this offers a useful approach to that group of writers which can be loosely designated as the New York Wits. Though it should not be supposed that the latter have the intrinsic importance, they do impose a paralyzing orthodoxy in taste and culture. This despite the fact that they originated a very few years ago in the rebellious PEN PENCIL POISON atmosphere which, in turn, claimed affinities with what James Huneker hailed with delight as “the poisonous honey of France.” It is necessary to consider the fact that whereas in the last century artists like Tennyson and Browning were crippled, at least subconsciously, by conventional pressure, today the reverse is true. An insipid and childish Bohemianism of stereotyped social revolt is the basic ingredient of popular taste. Literary fame today awaits the writer who provides conventional anarchism (misnamed “escapism”) in the spiciest ragout of Lear–cum–Carroll–cum-Wilde.

In the case of Alexander Woollcott and Dorothy Parker a more or less direct link with Swinburne, Wilde, and the ‘nineties, and kinship with Edna St. Vincent Millay, are admitted. Real but less direct connections with the ‘nineties exist also for such writers as Robert Benchley, James Thurber, Ogden Nash, and E. B. White. Thurber and Nash filter the revolutionary nihilism of a Wilde through the whimsy of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. They are avowedly less “caustic” than the formidable Woollcott and Parker. But taken together the Broadway Wits constitute our Bloomsbury and represent a tradition which has admitted authority in America. In fact it is hard to point to any other tradition which is at all comparable. Whether good or bad, there is no other national focal point for a whole complex of attitudes to current experience. Beneath this level is Hollywood and the chaotic world of best-seller narrative. To one side stands a tiny group of writers and readers of serious interests. But here is the meeting ground of highbrow and middle-brow. After thirty or more years THE NEW YORKER continues to provide this ground today. Nobody could ask a more immediate evidence for this fact than Edmund Wilson’s acceptance of his present job on the magazine.

Minority culture in America has mainly been concerned with the problem of absorbing European influences. From the beginning of American letters surprisingly little attention has been given to popular art and entertainment – a fact which betrays a radical flaw in minority culture. How little this attitude can afford to be indulged today should be clear if only from the fact of the great influence which American popular art has had abroad – particularly jazz and the movies. The failure of American writers to direct a strong critical light on popular art may be due to their own sense of futility, or it may proceed from a defect of political awareness – a failure to note that art and education, which include minority thought and feeling, are indivisible from the total life of the nation. From no point of view is such neglect defensible. The results are debilitating to high and popular art alike. The fact that the New York Wits have been immune from serious critical attention has meant a real loss to American letters and education. For here is a group of writers at once enjoying popular approval and a reputation for lively intelligence and artistic accomplishment. A major focus for critical effort presents itself.

A glance at some of the phrases which Louis Untermeyer applies to the “skin-tight” verse of Millay suggests their equal applicability to the verse of Dorothy Parker: “gay impudence,” “pitched in the key of loss,” “heel-and-toe insouciance,” “celebrates eager dawn or headlong day,” “preoccupied with the water darkening,” “in love with lost love, with the shards of her broken pot.” These notes are quite as apt for Dorothy Parker, for whom many would also claim the tribute Untermeyer bestows on Millay’s RENASCENCE: “It is as if a child had, in the midst of ingenuousness, uttered some terrific truth.” The laughable ambiguity of this MOT deserves treatment in a Thurber cartoon. But what are we to conclude from Mr. Untermeyer’s omission of Mrs. Parker from his heavily padded MODERN AMERICAN POETRY? If derivative debility is the criterion of admission, as it seems to be for nine tenths of the exhibits, why isn’t Mrs. Parker there? Miss Millay refracts her Shelleyan vehemence and wild emphasis through Mrs. Browning and a handful of Elizabethan epithets; Mrs. Parker refracts hers through the would-be austere naiveté of SHROPSHIRE LAD.

Both poets exploit long-established poetic fashions, appealing to a semi-alert audience which is glad to recognize hackneyed sentiment in a CHIC (that is, expensive) modern setting. Ever since being up-to-date has exerted the pressure of time-snobbery people have been as anxious to conform to the Zeitgeist in art and literature as in politics and morals. The net result has been a notorious time-lag and deadening of sensibility. Edna Millay, for example, has never been anything but a purveyor of cliché sentiment. She is an exhibitionist with no discoverable sensibility of her own. The pretentious rhetoric of the “unimpeachable body” variety won’t stand a moment’s scrutiny. Had there been responsible critics to consider her first work some direction might have been given to her talent. As it is, she is taken seriously in academic circles today. Vigorous and uncompromising criticism is indispensable to the fecundating of any kind of artistic ability. The lack of such criticism is not only indirectly fatal to the emergence of good work but permits every sort of humbug to flourish and to steal the soil which might nourish the real thing.

Mrs. Parker exhibits a mechanism of sensibility which is about as complicated as a village pump, though it masquerades as daring Avant Garde naughtiness and revolt. As she said of Katherine Hepburn, the Edna St. Vincent Millay of our stage, she “runs the gamut of emotions from A to B.” Her lyrics are charged with masochism and self-pity, while her prose is uniformly sadistic like her famous social PERSONA. So Woollcott’s whimsical statement that she is a blend of Lady Macbeth and of Little Nell is an unintentionally deft but damaging analysis.

In her stories one can watch Mrs. Parker emptying the vials of fastidious aristocratic scorn on painfully plebeian folk. To prevent any uneasiness in the reader, Mrs. Parker is careful to select an object of painful insignificance:

“She was tall, pronounced of bone, and erect of carriage; it was somehow impossible to speculate upon her appearance undressed. Her long face was innocent, indeed ignorant, of cosmetics, and its color stayed steady…. She had big trustworthy hands…. Gerald Cruger, who nightly sat opposite her at his own dinner table, tried not to see her hands. It irritated him to be reminded by their sight that they must feel like straw matting and smell of white soap. For him women who were not softly lovely were simply not women. He tried too, so far as it was possible to his beautiful manners, to keep his eyes from her face.”

Such is Horsie, a trained nurse, and symbol of obvious virtue and all that isn’t CHIC. Apart from the fact that the description reads like a menacing advertisement for some beauty aid, it is a tissue of hackneyed phrases held in place by a superabundant snobbery – sex snobbery, money snobbery, and social snobbery. To this array is commonly added an intellectual snobbery which has the same basis of imaginary superiority. Nothing more is to be found in Mrs. Parker’s stories than the simple conviction (which she may have picked up in her copywriting days) that “people stink” – perhaps explaining her famous phrase: “Inseparable my thumb and nose.” The people who stink least are those who have been disinfected by money and a knowledge of the smart ways of spending it (PACE Hergesheimer). Involuntarily or not, Mrs. Parker’s prose carries on a campaign for a commercially but otherwise painlessly acquired sophistication. Her eye for character is that of a Hollywood scout; and her frequent attempts to achieve what she calls “delicate disdain” plunge her into plain vulgarity. Together with the rest of the New York Wits, her work reinforces the same “smart” attitudes as the following advertisement which was written to scare English Public School boys of all ages:

“The Chester Spat approves of the man… who can read a wine list and know that Rudesheimer means Rhenish – but is also aware that bread-and-cheese and beer make a satisfactory meal… who knows that claret is best with an early pheasant and Burgundy with a late – but finds coffee-stall coffee at two in the morning superb with a saveloy… who goes to the Grand Opera because he likes music – and not because opera is grand… who can have his flat furnished by Djo-Bourgeois, without thinking Sheraton dull – and appreciate Matisse while still admiring Michael-Angelo….”

If anything, the brand of tongue-and-grooved SAVOIR FAIRE indicated here is a cut above the Parker-Benchley-Thurber grade. But they yield nothing in smugness.

Woollcott’s “picture of our Mrs. Parker” is pure Thurber:

“wringing her hands at sundown beside an open grave and looking pensively into the middle-distance at the receding figure of some golden lad – perhaps some personable longshoreman – disappearing over the hill with a doxy on his arm.”

And Thurber’s is the proper medium for expressing the richly ludicrous wares of “one who thought often and enthusiastically of death, and one whose most frequently and most intensely felt emotion was the pang of unrequited love.” Woollcott seems to have been uneasily conscious of “our Mrs. Parker’s” involuntarily comic aspect if only because of her great facility in striking these attitudes – and in striking the jack-pot at the same time. There are no personal pressures in the runways of this verse.

Emily Dickenson may well have been an influence:

“Parting is all we know of Heaven

And all we need of Hell.”

Emily may also, as much as Housman, have incited her to the tight-lipped monosyllables. Certainly SHROPSHIRE LAD – Dowson or Wilde “gone to earth” and become yokel or folksy – is everywhere so apparent that Mrs. Parker can really claim to be a Shropshire Lass:

“Who are you, my lad, to ease me?

Leave your pretty words unspoken.

Tinkling echoes little please me,

Now my heart is freshly broken.”

Sweeping gestures of bitter disillusion and noble renunciation – the prerogative of a carefully prolonged adolescence – with the full Housman flavor, are ubiquitous:

“So little I’ll offer to you, my lad;

It’s little in loving I set my store.

There’s many a maid would be flushed and glad

And better you’ll knock at a kindlier door.”

Like Housman’s, the simple rocking-horse rhythms (the nursery motif is always latent) convey the immediate sense of carefully nurtured and deeply enjoyed misery. (Housman’s sadistic prose is a match for Mrs. Parker’s.)

The staple conflict in Mrs. Parker’s world is familiar FIN DE SIECLE boredom with convention:

“But better a heart a-bloom with sins

Than hearts gone yellow and dry.”

Sometimes it is refracted in TREASURE ISLAND style through a glass flushed with gore:

“I’d like to straddle gory decks

And dig in laden sands,

And know the feel of throbbing necks

Between my knotted hands.”

This vista also enables us to see the connection between Mrs. Parker’s lyric crest and the great trough of thriller fiction which nourishes her sophisticated admirers between whiles.

For the rest “Living for a hating, Dying of love,” the sweets of sin which leave a face “white with woe,” the discovery that “Lips that taste of tears, they say, Are the best for kissing,” that she is “a most bewildering little shade,” or “kinder the busy worms than ever Love,” all this is part of the day’s work for Mrs. Parker. Important stage-properties in this verse are a rose-littered but deserted bed of passion, and a wet window-pane giving onto a wild sea shore littered with wrecks:

“So let a love beat over me again,

Loosing its million desperate breakers wide.”

The social phobias and distress of the 19th Century which led Dowson and the rest to revamp this limp Byronic stuff have shifted. The audience now cannot help but go backstage in daylight to examine the horrendous imagery. At best it was never more than self-indulgence. Today only an eager yearning for a similar indulgence can render it convincing. Mrs. Parker is often quite aware of her own banality (usually much less pretentious than Millay’s). She candidly stresses it:

“Once you go out, it’s done, it’s done;

All of my days are gray with yearning.

(Nevertheless, a girl needs fun.)”

It is, perhaps, this readiness to admit the flimsy pretenses of a lucrative racket that moves Mr. Untermeyer to exclude her. Among her admirers this frankness passes for hard-boiled cynicism, and for them Mrs. Parker is a poet full of “pawky insolence” and “bewitching surprises.” A tribute written for another “light-verse queen” (by Carl Sandburg) may be usefully transferred to Mrs. Parker. She has

“what Ophelia had before Hamlet’s fate drove her to the brink and the shadows. She is a sort of colleen and doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry at life’s fitful fever. You think she is going to cry and she gives you the ha ha. You figure it’s about time to laugh and she is walking off to have a good cry….”

The case of Alexander Woollcott is simpler. His success and ultimate literary dictatorship were built on a perfect adjustment to the main channels of conventional feeling gouged out by many an antecedent best-seller. And he was a master of the chiselled phrases in the slangy sense of that term. With many a hardy tug at the cords of “laughter and tears” this “caustic wit” ended his career in a Dickensian glow of public favor. His mechanical technique is seen at work in his account of Maude Adams’ return as Portia:

“For instance, I was not unaware of several comely minxes but recently arrived in their teens who were sitting just behind me. When we came by the moon-drenched loveliness of the final scene and heard from Lorenzo how the floor of heaven was thick inlaid with patines of bright gold, the young females behind me giggled. I realized that, to them, bred at the movies, this scene was just a coupla young people in funny clothes necking in a garden. And right they were, I suppose. But beyond them stretched an acre or so of grey heads, and at some familiar gesture of this Portia, or at some fondly remembered caress of the funny, throaty little voice, which ever defeated the mimics of its day, a ripple ran across that audience as a gust of wind traverses a field of grain – a ripple that was part a sigh and part contented chuckles and, to my notion, most pleasant to hear.”

The adoring reader who is expecting the reputedly irreverent old scalawag to pin some acrid little phrase on the performance has to stuff a handkerchief in his mouth as he sees a hebdomadal hand raised by the suddenly austere custodian of hallowed sentiment. These artful little shifts from grave to gay, from the naughty to the edifying, from scenes of human gore to mighty jousts at croquet and cribbage with the celebrities of the moment, - these are his stock-in-trade. Woollcott set up a nostalgic peep-show of scandalous or touching scenes from the past and present. The titillated public came eagerly because the owner of the show posed as an amiable but incorrigible rake, a man whose twinkle advertised a youth full of naughty Bohemianism. The public was flattered to recognize an ally.

Woollcott was a sort of Thackeray of Broadway, presenting an extremely vulgarized version of the mellow clubman’s faith that boys will be boys, and adding with a heavy ogle, “just as long as girls are girls.” His links with the ‘nineties are the obvious ones: nose-thumbing at stuffy conventions in art, education, and morals, arduous cultivation of a picturesque, Bohemian reputation, the claiming of immunity from social criticism on the ground of being irresponsible first as a child and second as an artist, and a deep-seated social snobbery disguised as a disregard for the adventitious celebrity of one’s casual acquaintances. As in the case of Wilde, the craving for social position and power was indirectly gratified by assault on those things. The “rebel” got his entrée easily enough, and had no trouble in dazzling his hosts with boyish mischievousness and an exuberant array of shop-worn rhetoric such as even Lytton Strachey may have admired.

Apropos of “the heartwarming benediction of Father Duffy’s smile” Woollcott says:

“I seem to remember it more often than not as a mutinous smile, the eyes dancing, the lips puckering as if his conscientious sobriety as a priest were once more engaged in its long, losing fight with his inner amusement at the world – his deeply contented amusement at the world.”

There is what Woollcott would call the heart of the humorist’s mystery – a deeply contented amusement at the world. Here is the sordid and abysmal root of both Victorian and modern whimsy-whamsy – a profound self-contentment, an almost solipsistic self-satisfaction manifested as condescendingly playful mockery. We shall see it below in Thurber. Basically there is much more humanity and generosity in the strutting diabolics of Wilde or Millay than there is in the superficial gentleness of Benchley or Thurber.

The shoddy unreality and bankruptcy of the world of Woollcott invites attention on every page. One reason for this may have been his eager insistence on just how wonderful were the objects of his approval. His pathetic overvaluation of the objects in his world was almost a mania with him – perhaps his way of disguising his utter lack of faith in anything. As an example, a meditation on death goes in this vein:

“It is a life thus successively and irremediably impoverished which you yourself give up at last…. At least that is the feeling I have when I try looking squarely at the fact that I shall never again read a new page by Lytton Strachey, never again hear the wonder of Mrs. Fiske’s voice in the theater…. These I have loved…. No more to feel sweet sunshine or hear blithe voice of living thing.”

One can see the wretched mechanism at work, transferring Rupert Brooke and the lines from THE CENCI into Broadway twitter.

The books, the pictures, the music, the people, as well as general attitudes toward society, enthusiasm for which is vigorously required of all who would make the grade as associates of the New York Wits, are belligerently middle-brow, that is, derivative. People like Proust, Joyce, Freud, Picasso, Eliot, and Wyndham Lewis are grudgingly admitted to exist but only so far as there is agreement that they are queer folk who have lost their moorings. But let some small game appear, let A. A. Milne cross Dorothy Parker’s path, or let Joseph Hergesheimer fall into the clutches of Mr. Fadiman, or some old numbers of PUNCH into the hands of Mr. Thurber, and watch the slaughter. Here is E. B. White enjoying himself at THE NEW YORKER level while some herd fodder comes under his eye:

“Then one day… came Wamba to my bedside with a copy of HARPER’S BAZAAR and a copy of VOGUE. ‘Ah brought you couple magazines,’ she said proudly, her red gums clashing.

“In the days that followed (happy days of renewed vigor and reawakened interest), I studied the magazines and lived, in their pages, the gracious lives of the characters in the ever-moving drama of society and fashion. In them I found surcease from the world’s ugliness, from disarray… through them I escaped into a world in which there was no awkwardness of gesture… no people of unimportance.”

Mr. White is quite able to see the fraudulence of the proffered world. But one soon discovers that all this serves merely to set Mr. White purring with contentment born of a conviction of superiority. He fondles the absurd ads and displays. To reject them, to puncture them too completely would be to deprive himself and his readers of a main solace, a solitary prop in a confused world. This is truly to live off one’s own parasites.